It has been said that journalism is the first rough draft of history. While this lends a bit of credibility to those whose job is to gather and report the news, it also suggests that what shows up as news is inherently subject to revision.

Despite this encouragement to revise what is first reported, Americans have shown a great propensity to cling to those accounts that initially titillate our curiosity over those which, in time, may inform our intellect. While this is certainly a problem in 2022, we can all rest easy with the knowledge that this peculiar human habit is not unique to this century; nor the last.

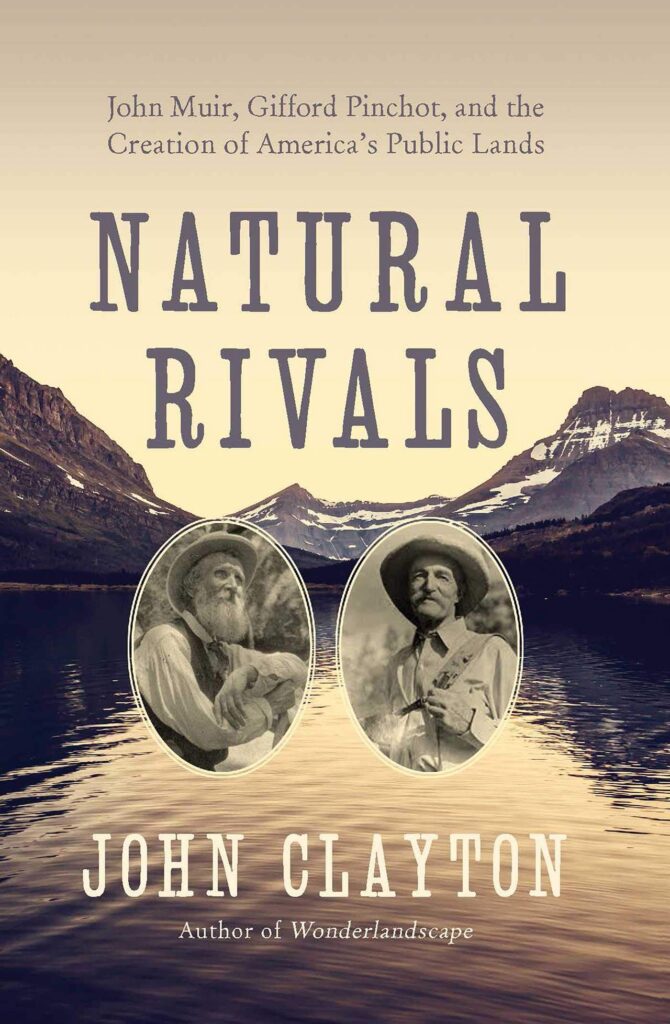

In Natural Rivals: John Muir, Gifford Pinchot, and the Creation of America’s Public Lands (2019), environmental historian John Clayton offers that sometimes those first rough drafts can have some staying power. In this case, it has long been held that naturalist John Muir and Gifford Pinchot, the founder of the United States Forest Service, engaged in epic battles over the use of land.

Muir is the famed wanderer and founding president of the Sierra Club often referred to as the Father of the Nationals Parks. His well-documented reflections demonstrate a spiritual connection to the landscape, especially those grand vistas such as Yosemite and Yellowstone which today are properly regarded as national treasures.

Pinchot—the first leader of the United States Forest Service—of the government and close adviser to President Theodore Roosevelt, upheld a more utilitarian view; evaluating the land and its resources in terms of the immense and potentially enduring power it holds to improve our lives.

As Clayton points out, the origin story of their “feud” devolves to an 1897 meeting between Muir and Pinchot where the two allegedly engaged in a heated exchange over the damage caused to the landscape by grazing sheep. While this version of events can better be attributed to sustainable gossip than news, by the time both Muir and Pinchot engaged with noted conservationist Theodore Roosevelt, several legends such as this arose in their wake. Following Muir and Roosevelt’s famous camping trip to Yosemite, many tall tales made their way in the country’s lore. As Clayton quips, “The best stories are always told by those who weren’t actually there.”

While the sheep-grazing story may seem trivial, it had enough legs (sorry) to be dramatically portrayed in a Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of John Muir almost a half-century later.

Energizing exaggerated claims of the animosity between Muir and Pinchot was their widely reported and years-long debate over damming the Tuolumne River as it flows through the Hetch Hetchy Valley in the northwest corner of Yellowstone National Park. Muir fought to preserve the natural valley while Pinchot prioritized the down-river water needs of the growing city of San Francisco. Unfortunately, the binary decision—either the dam was to be built or not—left little room for nuance. As Clayton writes, “the easiest way to illustrate the [largely fabricated Muir-Pinchot] divide is to describe [them] at Hetch Hetchy [as if] the two men were implacable enemies.”

Journalists and then later historians often looked to the debate over Hetch Hetchy as illustrative of an environmental divide pitting nature-loving preservationists against conservationists willing to negotiate away precious resources. And, Muir and Pinchot became the faces of that divide.

Hence, for much of the twentieth century, as Clayton observes, “almost every dam, mine, grazing allotment, timber sale, proposed wilderness area, national park, or national monument—every decision about priorities on public lands—has been argued as an expression of this preservation-versus-conservation divide.” As a result, “Conservationists get accused of too much compromise with short-term extraction; preservationists get accused of elitist and out-of-touch disdain for human society.”

Unfortunately, this dichotomous approach misses the broader and much more complicated circumstances that surround land use decisions.

It wasn’t until the 1990s that it became clear that the Muir-Pinchot 1897 meeting in which it was said that “Muir exploded in fury” at Pinchot while his “eyes were ‘flashing blue flames…’” very likely did not occur. Further, Clayton’s analysis of their relationship reveals that a century of assumptions about it – not to mention the environmental divide it portended to reflect – were misleading at best.

As Clayton surmises from a mountain of evidence, including extensive written communication between the two “natural rivals,” their differences in approach “simply offered alternative paths to articulating a constructive societal relationship to nature… The rivalry of Muir and Pinchot offered different reasons to move beyond short-term exploitation [of the environment].”

As Muir and Pinchot (and many others) engaged in healthy debate regarding preservation and conservation, the very foundation of their exchange was the management of—and hence the necessity of—public land in the first place.

While the Hetch Hetchy project moved forward, the ostensible loss actually became a triumph for John Muir’s cause. In an irony of epic proportions, Muir’s failure to prevent the damming of the Tuolumne at Hetch Hetchy alerted the country to what was at stake. Three years after Woodrow Wilson signed legislation in 1913 to dam the river, the National Park Service was created protecting existing and future parks from a similar fate. Today, national parks exist to preserve pristine areas that symbolize John Muir’s spiritual relationship with the land.

The timing of the Hetch Hetchy debate also found purchase with an American populace ripe for reforms of all sorts. The Progressive Era of the early twentieth century took account of the potential damaging effects of unfettered capitalism in an industrializing and urbanizing age. As John Muir and Gifford Pinchot illustrate, the result was “a productive tension that started changing people’s attitudes about land ownership.” During the course of this rivalry, it somehow dawned upon the American psyche that holding selected lands as the property of all the people is a good idea.

While other public lands are not so broadly protected as national parks, what is to be done with “democracy’s lands,” as Clayton describes them, is up to us.

Today, the National Park Service, the United States Forest Service, the Bureau of Land Management, and the United States Fish and Wildlife Service oversee more than 20% of the land in the country; the vast majority of it found in the West. That amounts to roughly 600 million acres of publicly owned and managed land.

Debates over public land use continue. Grazing and logging rights are curtailed with the future in mind. Drilling and mining interests must be measured against sustainable energy production and the climate health of the planet. And, as we strive to become a more moral people, we must continue to recognize that the public lands we speak of were largely occupied when brought into the fold of the United States.

For those who obsessively see private property rights as sacrosanct and the federal government as a bloated infringer of individual rights, the idea of public land is a travesty. For the rest of us with a less conspiratorial outlook, the conservation and preservation of public land must be viewed, in most cases, as a hallmark of good governance.

In Nature’s Rivals, John Clayton has reminded us that living in a democracy means sharing in the bounty of our country. For this historian, there is no better tribute to this ideal than public land and the encouragement to be vigilant in its care.