The first line of The Johnstown Flood: the Incredible Story behind One of the Most Devastating Disasters America Has Ever Known (1968) reads: “Again that morning there had been a bright frost in the hollow below the dam, and the sun was not up long before storm clouds rolled in from the southeast.”

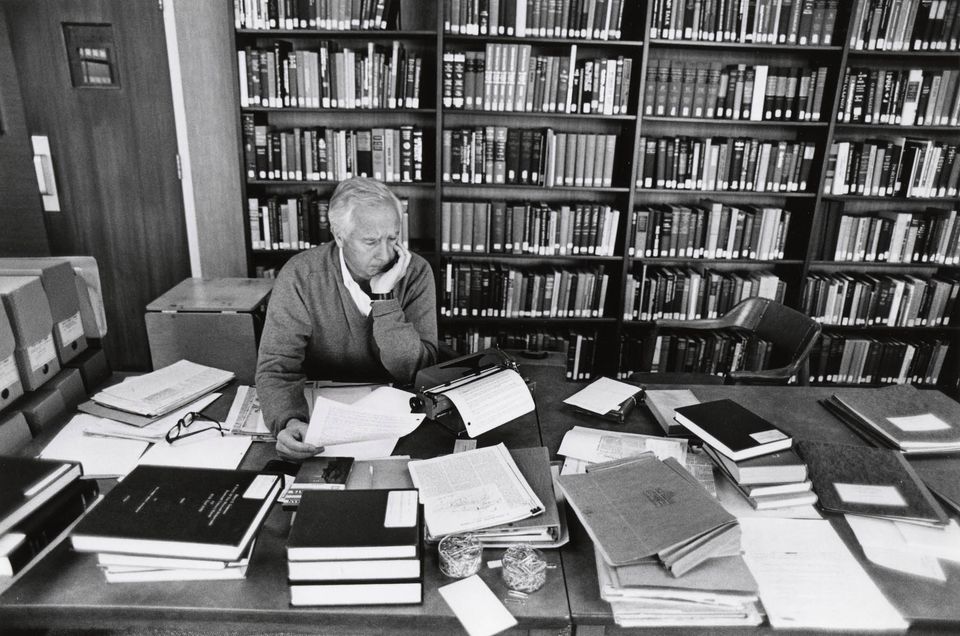

Thus began the remarkable career of popular American historian David McCullough who passed away on August 7, 2022 at the age of 89.

For over 50 years, McCullough popularized narrative history by telling the human stories of people caught up in larger events. When not writing books, McCullough traveled the country and mesmerized audiences with his uniquely calming yet authoritative voice. He was host of American Experience on PBS Television from 1988-1999 and he narrated The Civil War by Ken Burns in 1990.

As popular as McCullough has become, he has been widely criticized by academic historians for, among other things, “white-washing” our nation’s past.

For example, in The Pioneers: The Heroic Story of the Settlers Who Brought the American Ideal West (2019), McCullough was criticized for romanticizing white New Englanders who settled in and around the Ohio Valley when this part of the country was the West. In doing so, McCullough’s naysayers claim that he dismissed what we have come to learn regarding the harsh treatment of the land’s native inhabitants.

One reviewer dealt a body blow to the historian many Americans consider a national treasure. Historian Neil J. Young claims that McCullough’s attempt to inspire falls short when propped up next to the truth.

“A sweeping narrative of decent, hardworking men who built this nation that also reminds us of our better selves — and the moral bearings to which the United States must rededicate itself. Given the state of the nation… The Pioneers might seem the needed balm for our ravaged age. If ever there were a time for heroes, surely it is now… But that romantic view is the book’s very danger… The problem of McCullough’s story owes to how closely it reflects, even if unintentionally, the white nationalist myth that undergirds Trumpism.”*

Ouch!

This same reviewer actively encouraged readers NOT to buy McCullough’s book suggesting that there is no space at all for McCullough’s stories.**

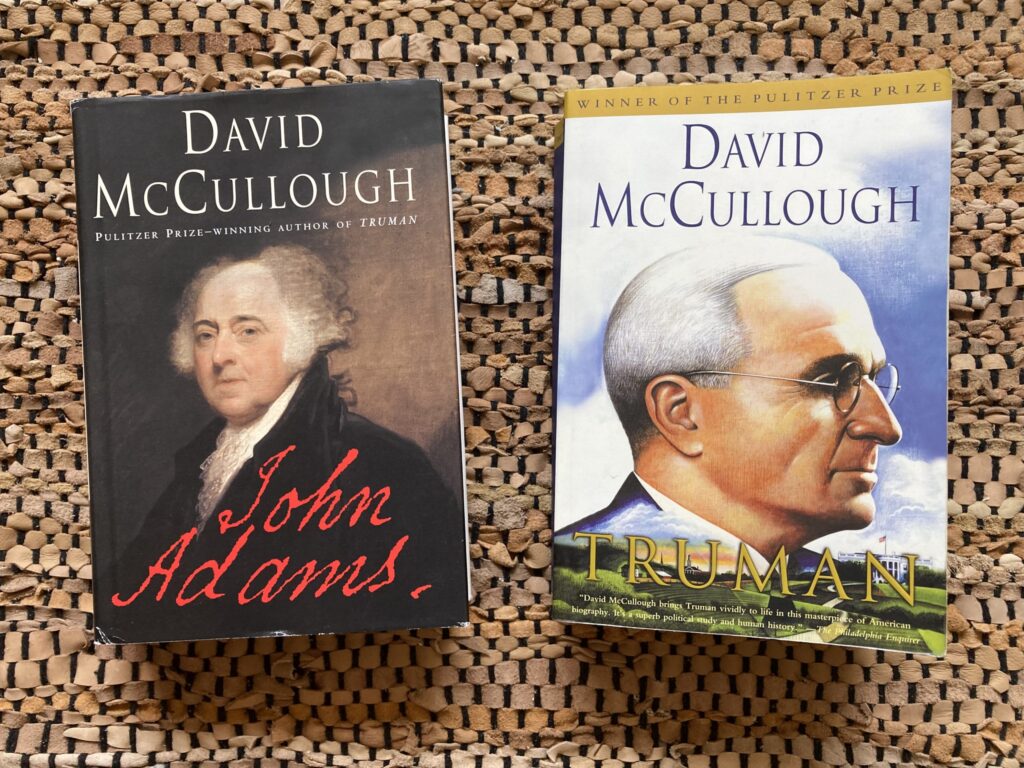

In Truman (1992), McCullough’s biography of Harry S. Truman, academic historians argued that the Pulitzer Prize-winning book was more a celebration of Truman rather than a critical analysis of the 33rd president of the United States.

A particular bone of contention was McCullough’s treatment of Truman’s decision to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. While the original justification for this drastic step—including the clear reality that the bombings would take tens of thousands of Japanese civilian lives—was that upward of a million American lives would be saved by bringing World War II to an immediate end.

More recent scholarship has challenged the morbid human math and suggests that the number may have been circulated to gain popular support for engaging in the unthinkable. McCullough has been criticized for dismissing this rather significant part of Truman’s life while cheering on the folksy Midwestern haberdasher who was thrust into the presidency and subsequently led the nation to glorious victory.

David McCullough has been up front about his admiration for Truman. In this, he chose not to take on the moral element of deploying a nuclear weapon so much as he argues that a rather simple man found the courage to make any decision at all regarding the lives of tens of thousands of people. I am not dismissing the debate over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, just suggesting that McCullough chose not to go there.

Some see McCullough’s omision as an egregious oversight, but this is an opportunity to engage with the topic in a manner that is inspired by good history… history that makes us think. And this, really, is the point.

In a more general example of critiques of McCullough’s entire body of work, academic historians who celebrate the monograph—a very specific, deep dive into a narrow subject within a bracketed time period – have complained that his stories often attend to the superficial at the expense of diversity, complication, and nuance.***

I discussed this “popular” versus “academic” history debate with a few of my graduate history professors.

While they didn’t support completely rejecting McCullough and several other popular historians, they simply did not hold his type of history in high regard compared to the work of academic American historians such as John Ferling, T.H. Breen, and Simon Schama. If you have never heard of these guys, you are not alone and perhaps with this will begin to understand my defense of McCullough and Co.

If you are ever going to engage deeply with an historical subject, it is essential that the manifest history—the larger setting—is known. This is what David McCullough, Stephen Ambrose, Erik Larsen, Candice Millard, and a host of other popular historians have done for millions of readers. Further, inspired by David McCullough, as many of today’s popular historians have been, bestseller lists are now replete with entertaining and informative history.

I think I nudged my professors a bit in the direction of embracing popular history by pointing out something with which they were intimately familiar: Students who show up in their undergraduate classes often have very little knowledge of even the most basic aspects of our nation’s past. In other words, primary and secondary teachers in this country are woefully unprepared to teach the history that state academic standards demand of them.

“So many of our teachers,” McCullough said during a 2015 interview, “are coming out of college with a degree in education but no major in a specific subject. You can’t inspire people if you don’t know what you’re talking about or you’re just trying to stay a day or two ahead of the students you’re teaching.”***

For 25 years, this unsavory sentiment characterized the vast majority of my teacher colleagues. This includes, understandably, those called in to teach a stray history class to fill out the master schedule; and sadly, also, many of those allegedly certified by the state to teach American history.

Tragically, I have concluded that this history teaching deficiency has contributed to the mess we are now in. “I’m very irritated by people who profess their great patriotism and devotion to their country,” McCullough adds, “and take no interest in their country’s history.” In a society which ostensibly relies upon an informed citizenry, the results can be catastrophic. As McCullough continues, “I’ve been astounded at how many politicians know almost nothing about their country’s history.”

I’ll add that it has been my observation that citizens who are not educated in their country’s history are susceptible to versions of that history which more suit the nefarious goals of politicians scrambling for votes rather than a fair—and rational—accounting of our past. Indeed, many of the most tendentious arguments I have had over the past few years have been with those whose sense of history was shaped by a less-than-enthusiastic and poorly prepared history teacher.

This is the problem to which David McCullough dedicated himself. RIP.

*https://theweek.com/articles/845704/dont-buy-dad-new-david-mccullough-book-fathers-day

**https://www.greenvilleonline.com/

***Other McCullough histories have been met with wildly popular acclaim and a basketful of literary prizes. Despite the often-legitimate criticisms emanating from academia, I heartily recommend each and every one.

The Great Bridge: The Epic Story of the Building of the Brooklyn Bridge (1972)

The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal 1870-1914 (1977).

Mornings on Horseback: The Story of an Extraordinary Family, a Vanished Way of Life, and the Unique Child Who Became Theodore Roosevelt (1981)

John Adams (2001)

1776 (2005)

The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris (2011)

The Wright Brothers (2015)