Racial segregation in America has often been viewed through two lenses. In the South, Jim Crow laws separated the races in schools and other public spaces. This is de jure (by law) segregation. Outside the South, de facto (in fact) segregation is said to have occurred naturally as a matter of personal preference.

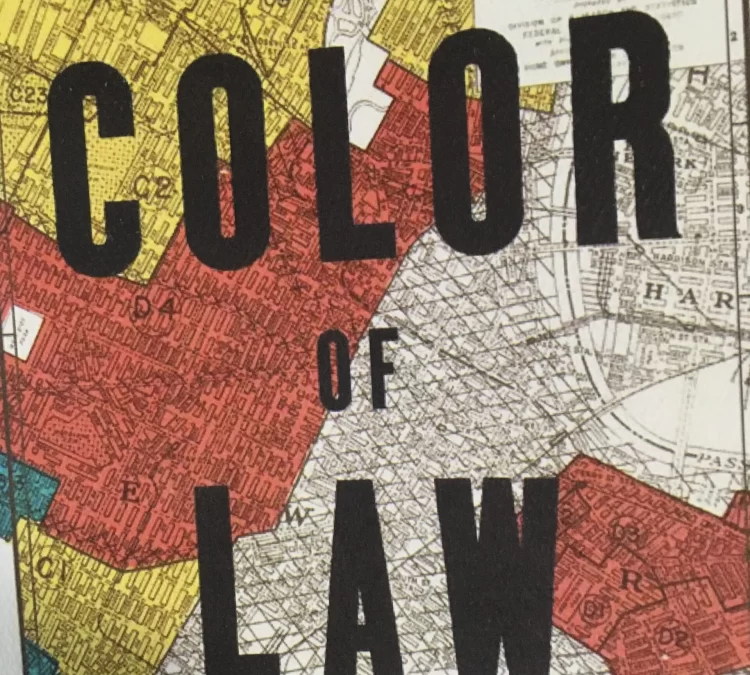

In The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (2017), Richard Rothstein destroys the de facto segregation myth by exploring how governments not only imposed racial segregation but did so in a manner that explicitly favored white America.

Like many myths, de facto segregation contains a kernel of truth. For instance, while I was teaching at a fully integrated middle school in Central Florida of the 1990s, the cafeteria reflected America. Black kids gathered at their tables. Latinos did the same. A number of Asian kids tended to join the white kids at theirs. At lunch, the students were permitted to sit wherever they chose and the result was a de facto segregated cafeteria.

The black students in the cafeteria also tended to divide themselves; those who lived in the middle-class town of Eatonville versus those who lived in a publically supported housing community affectionately known as “chocolate city.” Eatonville was founded in the nineteenth century and is considered one of the first successful all-black towns in the country. Chocolate city is, well, chocolate city.

I would learn later that this class division influenced the civil rights era much more than is taught during Black History Month. It also explains why many just don’t see that we continue to live in a heavily segregated society.

In The Color of Law, Rothstein demonstrates how these divisions today are the direct result of government intervention and that Jim Crow’s descendants are alive and well.

Beginning in 1934, the Federal Housing Administration’s practice of redlining explicitly labeled black neighborhoods in a way that severely limited black mobility. A single black family in a neighborhood could result in the FHA rating of “D.” Maps of these neighborhoods used by realtors and bankers showed them as red. Residents in redlined neighborhoods were explicitly denied access to federal programs that, in large part, helped to establish white home ownership and, subsequently, the American middle class.

The Color of Law offers many examples of how these policies were enacted across the country. I offer Detroit, Michigan as an example while the story in Motown mimics those of New York, Los Angeles and more.

I visited Detroit in 2015, while conducting research for my master’s thesis regarding the violence there in 1967. According to the US Census, from 1940 to 1960, the black population of Detroit lurched from less than 150,000 to over 482,000, a 220 percent increase. In 1940, less than one in ten Detroiters was black. Twenty years later, more than one in four were black.

Black and brown families across the country, by default, lived in redlined areas. They were forced to pay higher interest and insurance rates. Many were unable to secure mortgages so, instead, entered into purchasing agreements in which the slightest default saw many lose their homes.

In Detroit, as the city boomed during and after World War II, a housing shortage escalated racial tensions. White homeowner associations fought aggressively to keep blacks out of their communities. Pioneering blacks who challenged these racist housing practices paid the price; windows were broken, fences torn down, gardens trampled, lawns doused with salt and gasoline, car tires slashed, windshields broken.

Surprisingly though, a 1952 survey of racial attitudes in Detroit suggested that many whites were perfectly willing to accept a black neighbor. Their resistance grew, not so much from racial animus, but from federal government policies that threatened the value of their property.

Nefarious real estate brokers understood these federal policies created opportunities. In a practice known as block-busting, brokers offered to buy the homes of whites at “sell-before-the-neighborhood-turned” prices and resell them to blacks at immense profit. One gimmick involved hiring a black woman and her child to stroll through a white neighborhood to generate desperation among white sellers.

From 1934-1968, the federal government essentially denied black families the opportunity to acquire the multi-generational wealth which often accompanies home ownership. This is the same period when many white families rose out of the Great Depression and into the massive material prosperity of the second half of the twentieth century.

Other legally-sanctioned tactics to enforce segregation included restrictive deed covenants that forbade the sale of a home to African Americans; designing freeways to delineate neighborhoods and destroy low-income housing; and local zoning policies that used non-racial language to achieve racially-motivated goals.

Rothstein adds that federal policies continue to wreak havoc on people of color. When those white kids from the school cafeteria went out to buy their first home in the 2000s, many of them were able to secure mortgages at a fair rate and very likely with the help of family wealth arising out of multi-generational home ownership.

Many of those black and brown kids were able to do the same; at least those whose families came from Eatonville. Unfortunately, for those with chocolate city roots, federal lending policies of the early twenty-first century allowed banks to gouge these unsuspecting customers.

While many of these borrowers certainly made unwise financial decisions, Rothstein writes that “federally regulated” loans were “designed to make repayment difficult.” Many had extremely high closing costs and exorbitant interest rates or initially low interest rates that shot up over time. Other programs had negative amortization with payments less than accrued interest.

The hard reality is that these “homeowners” suffered the brunt of the financial collapse of 2008 and many were forced out of their homes and back into the impoverished areas from which they had fled.

Today, much has changed. Laws that segregated have been stricken. Their legacy, however, remains; not in the lightly integrated world in which many white Americans live, but within the hundreds of chocolate cities that dot the American landscape.