In August 1974, when I was 14 years-old, Richard Nixon resigned as president of the United States under a cloud of lies and malfeasance. The next month, I began my journey from Cincinnati, Ohio to Southern California under no clouds at all.

For someone who fancies himself attuned to the political goings-on in this country, it is curious that I only recently considered that running away from home was somehow related to Tricky Dick’s political demise.

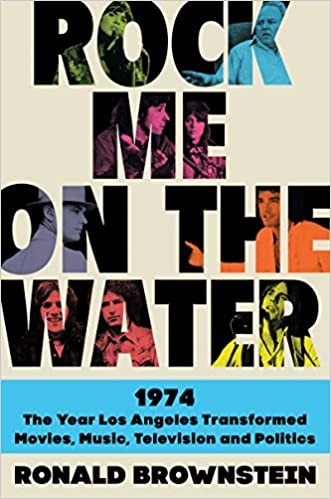

My reminiscing has been inspired by reading Rock Me on the Water: 1974—The Year Los Angeles Transformed Movies, Music, Television, and Politics. Written by journalist, political analyst, and now-historian Ronald Brownstein, Rock Me portrays the disillusioned cultural echoes of revolution-gone-bad. From roughly 1967 to 1976, Los Angeles served as the heartbeat of this transformation.

Brownstein situates 1974 as the through-line of this decade, characterized by the reaction to the near-complete failure of 1960s pronouncements of social and political rebellion. The music, movies, and TV of the early 70s—for the first time—began to reflect the issues that had so energized the Baby Boom generation; questioning authority, experimenting with sex and drugs, and perhaps most importantly, imagining a world that thoroughly rejected the stifling bigotry and provincialism of the 1950s.

The election of Richard Nixon in 1968 was a gut check to these ideals while his re-election in 1972 served as a death knell. The new political reality was countered with a cultural reckoning that, for only a brief moment, attempted to codify through movies, TV, and music whatever might be salvaged from the ash heap of the 1960s. Brownstein writes: films portrayed America as suffused with hypocrisy (Shampoo, Nashville) and built on corruption (Chinatown, Godfather II); television shows (led by All in the Family, M*A*S*H, and Mary Tyler Moore) brought tensions over the Vietnam War, the ‘generation gap,’ race relations and the sexual revolution into the nation’s living rooms; and classic albums from artists such as James Taylor, Carole King, Joni Mitchell, Jackson Browne, and the Eagles… chronicled the search for new markers of meaning in life beyond the yardsticks of suburban success that listeners had been raised on.

Within a generation largely defining themselves as “anti-establishment,” it is amazing that the industries producing this norm-busting entertainment were still controlled by old wealthy white men who were more inclined to celebrate America than to question it. Or, perhaps not so surprising, these men gave in to their most basic impulses by capitalizing on the massive buying power of a Baby Boom generation coming of age in the 1960s.

While the idealism of that decade did not result in serious political change, the images and sounds emanating from L.A. in the early’70s charged the cultural atmosphere that kept alive the spirit of those ideals.

In contrast to Hollywood’s patriotic and propagandist films that had loyally celebrated America, Brownstein offers that films of this new strange era “fundamentally challenged America’s self-image as an equitable society and a force for good in the world.”

On TV, Archie Bunker’s “language crashes like a rock through the television screen.” The commentary was delivered by a loveable bigot who, by design, was always one-upped by those he looked down upon. “The show’s most consistent political message,” Brownstein adds, “was that Archie (and all those who thought like him) could not stop the social and cultural changes happening around them.”

The music was more subtly provocative but filled with a potency only music can convey. A burgeoning LA mood fostered collaboration that, in turn, enhanced the virility of the message. Many of the artists, agents, and producers partied and made music together; living the lifestyle that was reflected in the music. “Much of the city’s social life,” Brownstein notes, “revolved around parties in private homes, the Bel Air mansions of Hollywood producers or the funky Laurel Canyon bungalows of the rock elite.”

As powerful as these cultural shockwaves were, they were also exhausting; and the country’s preferences changed once again. By 1976 Happy Days unseated All in the Family as the most popular TV program in America. The show that explored virtually every controversial topic of the day— racism’s hypocrisies, the folly of Vietnam, government corruption, the sexual revolution, and more—gave way to a throwback that reinforced the same myths that had been torn down.

In the movies, “commentary” ceded the cinematic pulpit to “spectacle.” In 1975, Robert Altman’s Nashville served up a biting indictment of American society but audiences decided to go see Jaws instead.

The fatigue was captured in Hotel California as the Eagles mourned the passing of an age: “We haven’t had that spirit here since 1969”—a classic lyric whose reading evokes the melody that backed it up.

I was only nine in 1969 and I have always felt as if I missed something by witnessing the most turbulent decade of the century through the eyes of a child. Now, as I cast my gaze to the decade of my adolescence—with an assist from Ronald Brownstein—I see that I didn’t miss so much after all.

It was late Sunday night that I stole myself out of the back of the row house on Chickasaw Street, carrying little more than a few PB&J’s, a jug of water, and about 20 bucks in coins and crumpled bills recently liberated from a piggy bank. I walked down to the Ohio River and crossed the bridge into Kentucky. With the Mason-Dixon Line now at my back, I somehow found the entrance ramp to Interstate 75 South. I extended my thumb and was quickly noticed by a twenty-something driver who thought he knew why I was there.

We drove quietly away from the lights of the city before he made his move. After a brief profanity-laced exchange, he pulled to the shoulder and told me to get out. It was dark. I wandered away from the freeway’s pavement and lay down in tall grass under the illumination of a towering Sunoco sign. As I settled into my sleep, it occurred to me that there was not a single soul on the planet who knew I was on my way to L.A.