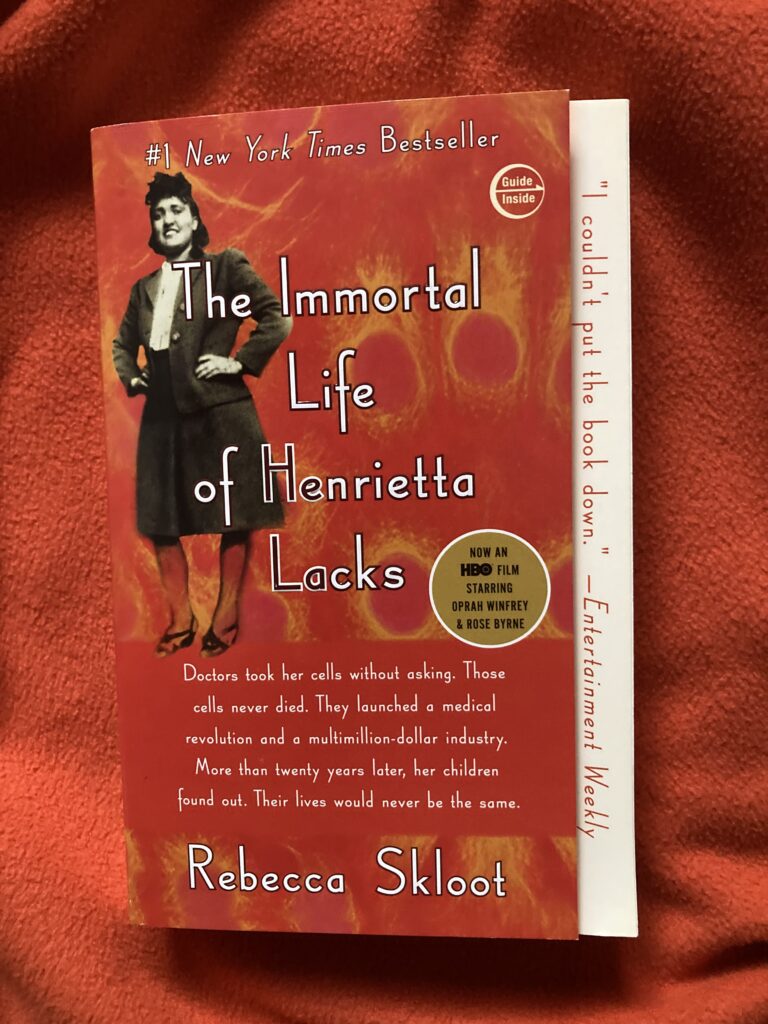

Good history illuminates the past, informs the present, and inspires reflection. Case in point: The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (2010) by Rebecca Skloot.

In 1988, high school science student Rebecca Skloot learned that Henrietta Lacks, a poor African American tobacco farmer from southern Virginia, had made an invaluable contribution to modern science; and just about everyone of us today has benefited from this contribution.

In September of 1950, Henrietta gave birth to her fifth child in the colored-only ward of Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland. Only a few months later, she returned to the hospital with abdominal pain and vaginal bleeding. Between those two visits, “an eroded hard mass about the size of a nickel” emerged on her cervix.

As it turned out, the doctor treating her was a pioneer in the field of gynecological medicine who had developed a new theory about cervical cancer; one which could be tested by gathering tissue samples. In February of 1951, he removed a small slice from the abnormal growth on Henrietta’s cervix. He discovered that these cells were like no others. They grew at an amazing rate and, most significantly, did not die off if kept in a proper medium.

For more than seven decades, the cells he collected that day have continued to reproduce in science labs around the world. (The cell-line is known as HeLa – Henrietta Lacks.)

HeLa cells have been used to create the polio vaccine. They have contributed to treatments in “chemotherapy, cloning, gene mapping, in vitro fertilization” and also used to develop “drugs for treating herpes, leukemia, influenza, hemophilia, and Parkinson’s disease; and they’ve been used to study lactose digestion, sexually transmitted diseases, appendicitis, human longevity, mosquito mating, and the negative cellular effects of working in sewers…”

Her cells have been used to study the effects of nuclear explosions and rocketed into space to study the effects of zero gravity. Most recently, these cells have been used to study COVID-19. “Like guinea pigs and mice,” Skloot writes, “Henrietta’s cells have become the standard laboratory workhorse.”

As Skloot recounted over ten years ago when her amazing research was published, “One scientist estimates that if you could pile all HeLa cells ever grown onto a scale, they’d weigh more than 50 million metric tons…”

This is an amazing number which has certainly grown since then; and all-the-more remarkable in that Henrietta, in her first incarnation, stood barely five feet tall.

But this is so much more than a science story.

When Skloot asked her science teacher long ago about Henrietta Lacks, all he knew was that she was an African American woman. And, as it turned out, by 2010 the tens of thousands of scientists who had used Henrietta’s cells didn’t even know that much. This is no longer true; thanks, in large part, to Rebecca Skloot.

Henrietta died shortly after the biopsy and had no idea that a part of her body had been taken for these purposes; and for over twenty years, neither did her family.

In 1976, a reporter for Rolling Stone magazine investigated the mystery behind the HeLa cells; which were thought by many to have originated with someone named Helen Lane. Twenty-five years after Henrietta’s biopsy, the Lacks family finally learned that her cells had transformed modern medicine.

While the handful of news reports that followed properly identified the person behind the cells; the larger human, moral, and ethical story went untold. That the cells had been taken and used as they were without Henrietta’s knowledge was simply not the issue in 1976 that it is today.

Investigating the story of a poor southern black woman who had died 25 years earlier meant gaining the trust of her family who, after learning how their mother’s cells had been taken and used without their knowledge, had every reason to question the motives of nosy white reporters.

And, in 1976 – and today for that matter—many African Americans have a deeply rooted mistrust of medical institutions and the government; and for good reason.

Most notably, from 1932 to 1972 the US government conducted research on syphilis at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama – an historically black university. Hundreds of black men with syphilis went untreated in order for doctors to observe the course of the disease; despite the availability of penicillin, a highly effective treatment. More than 100 of these men died and many of their wives and children contracted the disease.

Tuskegee scientists also helped develop the polio vaccine using Henrietta’s cells in the 1950s. In the harshest of ironies, as Skloot writes, “Black scientists and technicians, many of them women, used cells from a black woman to help save the lives of millions of Americans, most of them white. And they did so on the same campus – and at the very same time – that state officials were conducting the infamous Tuskegee syphilis studies.”

Skloot—a white woman—began the research for her book in 1999. When she spoke with a black doctor who had been a student of the tissue specialist who began growing the HeLa cells nearly a half-century earlier, he asked her, “What do you know about African-Americans and science?”

One of Skloot’s biggest obstacles, then, was gaining the trust of the Lacks family, particularly Henrietta’s daughter, Deborah. The manner in which these unlikely relationships unfolded over the course of a decade offer important insight into modern issues of race and the degree to which they have been shaped through generations of strife.

The results of Skloot’s decade-long investigation follow multiple story lines woven together with narrative flair. The science associated with the HeLa cells is fascinating, the Lacks family history is eye-opening, and the adventures of Rebecca and Deborah, over several years, is both tragic and heartwarming.

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks is also a classic illustration of the organic nature of history-writing. Medical and ethical norms of behavior have changed dramatically in the last 70 years.

Today, we view the HeLa story through the lens of issues that matter to us now; patient rights, informed consent, racial equality, privacy and genetic information, property rights (of our own bodily tissues), and so much more.

Good history also helps to set the record straight. When Deborah Lacks learned how significant her mother’s cells had become, helping literally millions of people, she asked Skloot, “if our mother cells done so much for medicine, how come her family can’t afford to see no doctors?” After uncovering the injustice, the intrepid science writer and historian promised Henrietta’s family that she would try to balance the scales a bit.

The promise has been kept in spades.

In 2010, Skloot founded the Henrietta Lacks Foundation whose mission is providing health care and education to the families of “individuals who have made important contributions to scientific research without personally benefiting from those contributions…”

Most recently, as a direct result of Skloot’s wonderful book, Johns Hopkins Hospital has announced that a new building will be constructed and named in honor of Henrietta Lacks. According to the director of the expanding Berman Institute, the research conducted there will “ensur[e] that we consider and help respond to the ethical issues that arise from innovations in medicine and science…”

Others have been spreading the word of Henrietta Lacks, too. I first heard an entertaining telling of her story at Radiolab, one of the finest podcasts out there. And, in 2017, Oprah Winfrey starred as Deborah Lacks in a film adaption of Skloot’s book.

Good history, indeed.