There is a great deal of chatter out there about our divided dysfunctional political system which now includes a growing incidence of references to impending civil war. While the folks who study these things see it as unlikely that two massive armies will form and slaughter one another on battlefields with familiar names – as was the case in the 1860s – they do tend to see a future where increasing divisiveness will lead to more violence.

If history is to guide us here, and I believe it can, we might be better off examining the lessons of the 1960s over the 1860s. Most Americans who are familiar with the 1960s have learned about this turbulent decade by studying history, but there are many who still remember living through the chaos, if only through their television screens. Indeed, by 1960, televisions were present in 90 percent of American homes. As in our own decade, technology was deployed as a tool to influence our understanding of, and reaction to, the madness.

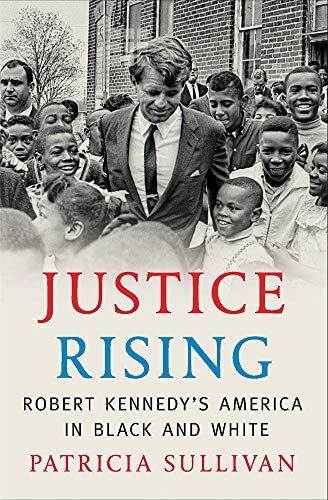

I think of all this now after reading an inspiring account of the life of Robert Francis Kennedy. In Justice Rising: Robert Kennedy’s America in Black and White (2022), historian Patricia Sullivan takes a refreshingly relevant and timely new look at RFK, fittingly known to all as Bobby.

A few key moments illustrate Kennedy’s humanitarian impulses and serve as a model for what we should expect from our political leaders.

In 1951, Kennedy joined his sister Patricia and brother John as they traveled throughout the Middle East and Asia to “Israel, Iran, Pakistan, India, Indochina, Singapore, Thailand, Malaya, Korea, and Japan. Bobby was 25, Patricia 27, and Jack [JFK] 34.” Nationalist movements throughout the region were attempting to cast off the yoke of centuries of European colonial rule. In an age when the Cold War conflict with the Soviet Union and the fear of the spread of communism defined American political interests around the globe, Bobby saw instead “the human misery driving the social unrest surrounding them.”

After visiting Vietnam which was then under French rule supported by the United States and more than a decade before the US would send hundreds of thousands of troops there, Kennedy seemed to grasp the situation clearly. “Our mistake,” he wrote, “has been not to insist on definite political reforms… as a prerequisite for aid. As it stands, we are becoming more and more involved to a point where we can’t back out.”

Many of the nationalist movements around the globe were inspired by some of the same principles that drove the founding of the United States while it was Cold War paranoia that drove American foreign policy throughout the 1950s and beyond.

In another instance, as Attorney General during his older brother’s presidency from 1961-1963, Bobby’s innate dedication to social justice was enhanced by his desire to learn about and respond to injustice.

On May 24, 1963, Kennedy invited Black writer James Baldwin and a variety of other African American cultural activists, including singer and actor Harry Belafonte, playwright Lorraine Hansberry, musician and actress Lena Horne, and sociologist Kenneth Clark to join him to discuss race relations in America at a Kennedy-owned apartment in Manhattan. Also present was Freedom Rider Jerome Smith, who “was in New York for treatment of a broken jaw and head injuries” sustained in his front-line efforts in the struggle for civil rights.

“Baldwin,” Sullivan writes, “had concluded that Kennedy did not understand the depth of the [race] problem and saw this as an opportunity to enlighten him.” This was one of the overriding themes of the entire civil rights movement; the pressing need to educate white people who, for the most part, simply did not understand the oppression under which millions of Americans lived. (In many respects, I believe that this ignorance continues to shape much of the harsh rhetoric of our own age.)

While the Baldwin-Kennedy meeting—as it has come to be known—left the civil rights activists frustrated that Kennedy was clearly as ignorant as other white Americans, Sullivan examines in great detail the deep effect this meeting had on the attorney general and, in turn, on his brother the president of the United States.

During a contentious moment, Lorraine Hansberry suggested to Kennedy, “Mr. Attorney General… the only man you should be listening to is that man over there.” She was referring to Jerome Smith whose wounds had been delivered at the hands of Southern white cops. “Smith assailed Kennedy,” Sullivan writes, “for the government’s failure to protect Black demonstrators in the South… Kennedy tried to answer Smith several times. Smith cut him off, ‘Okay, but this time say something that means something.’ Asked by Baldwin if he would fight for his country, Smith answered, ‘Never.’ Kennedy [was] visibly shaken… [and then] seemed to accuse Smith of treason.”

While Kennedy was shocked at Smith’s attitude toward his country, the revelation here was that the activists “were shocked that [Kennedy] was shocked.” This illustrated the problem at hand. Bobby Kennedy—and most white Americans—simply did not comprehend how a young American would refuse to defend his own country.

While originally seeming to castigate him for his lack of patriotism as the other activists came to Smith’s defense, it would become clear later that this fiery exchange had a profound impact on Bobby Kennedy.

A few weeks later, Kennedy said that the country was facing a moral dilemma, “but the main problem lies with the whites – they’re the ones who are denying Negro rights.”

On June 11, the language and temperament used at the meeting with Baldwin made its way into President Kennedy’s address to the nation. For the first time, a president acknowledged the moral dilemma the country faced. Laws protecting civil rights were all well and good but the real problem facing the country was in the hearts of its citizens. “Law alone cannot make men see right,” he said. This is the flip side of the segregation coin. Yes, segregation condemned African Americans to second-class citizenship. Yet, it also isolated well-intentioned white Americans who simply did not understand the dire circumstances under which their fellow citizens lived. As Kennedy reported that night, “we are confronted primarily with a moral issue.”

“Your speech to the nation,” Martin Luther King wrote to President Kennedy after his televised address, “was one of the most eloquent, profound and unequivocal pleas for justice and freedom of all men ever made by a president.”

Sullivan makes it clear that this enlightened moment was inspired by Bobby Kennedy listening to a young black man with a broken jaw.

King had only recently—April of 1963—made the same argument in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail” while police used fire hoses and dogs to attack young people who were marching in the city that had jailed him. King’s message was that people not only have the right to disobey unjust laws – such as those that segregated businesses in downtown Birmingham – but that all of us have a moral responsibility to do so. He appealed to moderate whites that “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

By July, the Kennedy administration, particularly Bobby Kennedy’s Justice Department, acknowledged that what had been widely referred to as the “Negro problem” was actually an America problem. “Now I understand,” the thirty-seven year-old attorney general told iconic civil rights leader John Lewis. Bobby Kennedy would spend the rest of his short life trying to help white Americans understand the reality and origins of racial strife.

As Sullivan writes, Bobby Kennedy “viewed white indifference, fear, and prejudice as the greatest obstacles to change – along with the public figures who played on those fears.” This sounds hauntingly familiar as I write in 2022.

Kennedy was elected to the Senate in 1964 and then ran for president in 1968. In that time, he dedicated himself to understanding a world that was starting to spin out of control; riots in hundreds of cities across the nation in a series of long hot summers, continued efforts to desegregate the South and the violent white backlash that followed, political assassinations, the quagmire of Vietnam and the volatility and divisiveness expressed through anti-war demonstrations.

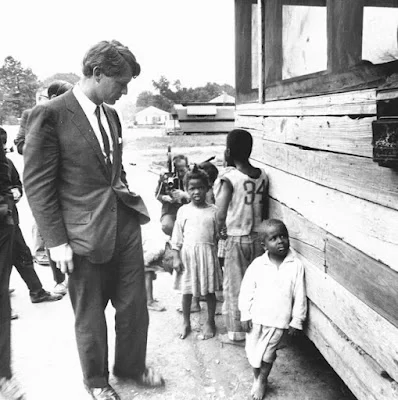

Bobby Kennedy was not deterred. He visited black neighborhoods around the country and spoke directly with people living in squalid conditions shaped largely by discriminating federal housing and urban renewal policies. He toured the Mississippi Delta and visited with people living in shacks with no running water or electricity and witnessed first hand the physical and emotional effects of starvation; even as Mississippi officials denied that these conditions existed. He visited with Cesar Chavez in support of immigrant laborers. He traveled to South Africa and spoke directly to white college students—as he had done in the United States—about the responsibilities they bore as a result of their privilege in a radically segregated country.

A sense of justice—which most of us have—must be complemented with understanding the presence of injustice. Bobby Kennedy’s life served as testament to this noble ideal.

Patricia Sullivan has reminded us of the deep cultural and political divisions we faced in the 1960s and how so frequently violence played a part. She also offers a glimmer of hope that in times of social upheaval, morally responsible leaders can emerge to guide us through it.

Sadly, Bobby Kennedy paid dearly for his courageous stand against injustice. Only minutes after midnight on June 5, 1968, a Palestinian-American shot Senator Kennedy, who had just won the California and South Dakota Democratic primaries in his bid for the White House. He died the following day.