In 1888, French inventor Louis Le Prince used a device the world had never seen to capture the first known motion pictures: a two second clip of his family walking in what is now referred to as the Roundhay Garden scene.* Shortly before announcing his invention to the world, Le Prince disappeared, never to be seen or heard from again. A few months after that, world-renowned inventor Thomas Edison announced his latest marvel, a moving picture machine.

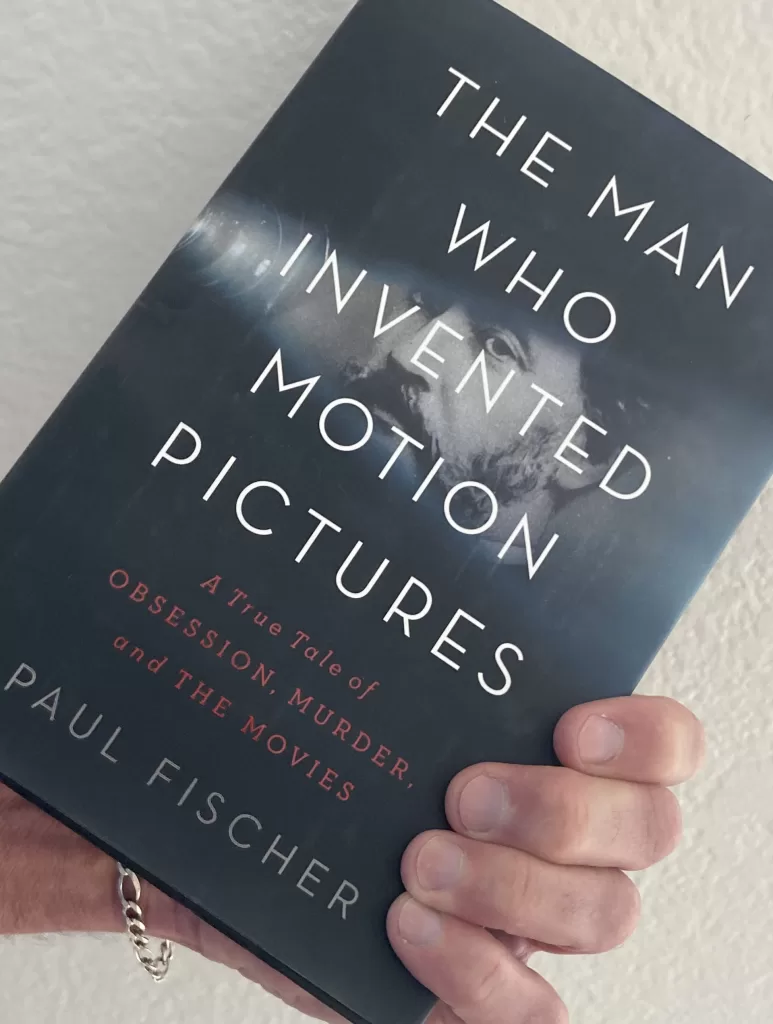

Louis Le Prince’s long-neglected story is told in The Man Who Invented Motion Pictures: A True Tale of Obsession, Murder, and the Movies (2022) by author, film producer, and film historian Paul Fischer.

Fischer clearly suggests that Thomas Edison’s achievements were as much a product of his material resources and manipulations of patent law as they were of inspiration and perspiration. He substantiates the plausibility of his argument by clarifying the atmosphere in which ideas often grow into inventions.

Our tendency to clearly associate an invention with a single inventor obfuscates the actual environment in which new innovations are often brought into existence. As Fischer writes, “There is a theory of invention that argues technological advancements are culturally determined and to a certain degree inevitable—that every one of a society’s discoveries lays the foundations for the next by bringing it into the realm of the conceivable.”

In the case of the development of the motion picture camera and projector, there were a number of craftsmen, artists, and scientists in the 1880s simultaneously working towards the same end. Further, a number of existing technologies supported the idea that motion pictures were “inevitable.” Among these were the processes for still photography, the use of multiple lenses, and a new medium for film—celluloid instead of glass plates

It was in this environment that employees in Edison’s lab were trying to develop motion pictures with a number of presumptions about how this might be accomplished while Louis Le Prince was doing the same thing; except with an entirely different set of presumptions.

Fischer documents clearly that the innovations being developed by Edison’s employee – W. K. L. Dickson —involved dramatically different features than the motion picture machine Edison later revealed. Le Prince filed a publicly available patent in 1888 that described the functioning machine and, as Fischer writes, “just weeks after Louis’s disappearance… [Edison’s machine] suddenly bore an uncanny closeness to Louis’s own patent.”

At one point, while trying to create a motion picture machine in Edison’s lab, with workbenches cluttered with tools, chemicals, and all sorts of parts, Dickson found himself “surrounded by other people’s ideas.”

The Thomas Edison we all learned about in grade school is portrayed in a much harsher light. Yes, he is still clearly a brilliant inventor; but he is also a rogue, a profiteer, and a cheat. Under pressure to live up to his early reputation as a genius, Edison, it appears, became much more adept at navigating the world of patent law than actually inventing many of the devices so closely associated with him.

Edison’s early success provided him with an infrastructure for invention; not just the resources to hire the best scientists, chemists, and craftsmen—like Dickson—but the ability to bring new ideas to the marketplace. This brought many independent inventors into Edison’s orbit. Marketing a new machine, Fischer explains, “might logically have been answered by a partnership with Thomas Edison.”

It is not clear that Le Prince made any deals with Edison but, as Fischer notes, “there were plenty of people who had trusted Edison and came to regret it.” One unfortunate soul angrily cried, “Thomas A. Edison can go to Hell.” And he added, “He hasn’t got anything that he didn’t steal from me.”

One legal maneuver that Edison deployed hundreds of times involved filing a “caveat” with the United States Patent Office; a description of an uninvented product with only the general ideas about how it might be created. Under our “theory of invention,” in an age where many were working to develop motion pictures, a caveat would support the claim that whoever later actually invented the machine could be accused of patent theft.

The subsequent and inevitable court battles were typically won by those with the most money and the best lawyers… you guessed it, Mr. Edison himself. As Fischer writes, patent caveats allowed Edison to “snuff out rivals” and to “claim entire lines of potential innovation as his own…”

In 1902, however, a judge “condemned Edison’s use of patents as a means to subvert the law” and then went on to describe all the different innovations that came together to make motion pictures possible, of which Edison had played no role whatsoever. Edison then used his wealth and influence to revise his patent and gain a new trial with a new judge. The result, Fischer laments, is that “[a]ll filmmakers not working for Thomas Edison or W. K. L. Dickson suddenly found themselves outlaws.”

Edison also made a deal with Eastman Kodak thereby monopolizing the trade in celluloid film. And, under the guise of the Edison Trust, a small group of inventors/businessmen were forced to cave into Edison’s demands by relinquishing their patents to him and, in the end, “went about putting everybody else out of business.”

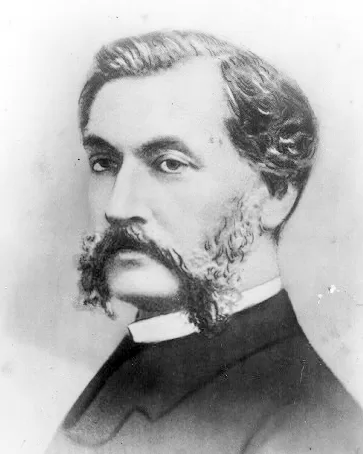

While Paul Fischer denigrates Thomas Edison, he brings to life the man he views as the true inventor of motion pictures. The genius behind Louis Le Prince’s invention lay primarily in his understanding of human physiology. At the University of Leipzig, Le Prince “studied optics and chemistry” where he “learned how the eye worked, how it turned what it saw into signals the brain comprehended as movement.” Therein is the innovation that bridged still photography with motion pictures. This is the genius behind the invention of the first motion picture machine. And the proof of the matter was filmed in Roundhay Garden.

The better story here is the obsession of Louis Le Prince. As Fischer writes, “[Le Prince’s] passion lay in the arts and, more precisely, in the intersection of arts and technology, the science of light and its interactions with the human eye.” And, unlike Edison, who is shown to have had only a fleeting interest in the marketability of motion pictures, Le Prince saw in his quest the betterment of the human race, believing that motion pictures would entertain, educate, and connect people.

I’ll say nothing to spoil the fascinating mystery of Le Prince’s disappearance. Years later, though, Le Prince’s widow Lizzie wrote of the potential of motion pictures to bring people together to solve their problems.

“[My husband] believed that moving pictures would prove more potent than diplomacy in bringing nations into closer touch, and that as a peace propaganda it was without a rival. What mother,” she added, “who has watched a realistic reproduction by camera of a battlefield in action would see her son become food for cannon in an unnecessary war?”

Technology does indeed have the potential to bring mankind closer together and, as we have seen in our own age, it also has within it the capacity to tear us apart. Either way, I believe we are all better off when we get our history straight. In that, Paul Fischer has certainly done his part.

*Here is a pair of 2-second clips, the first ever moving pictures directed by Louis Le Prince.

[…] one of the stronger pieces of evidence that Edison was an invention thief was in his habit of using caveats. A patent caveat is basically an IOU to the patent office that translates to “Hey, I have this […]