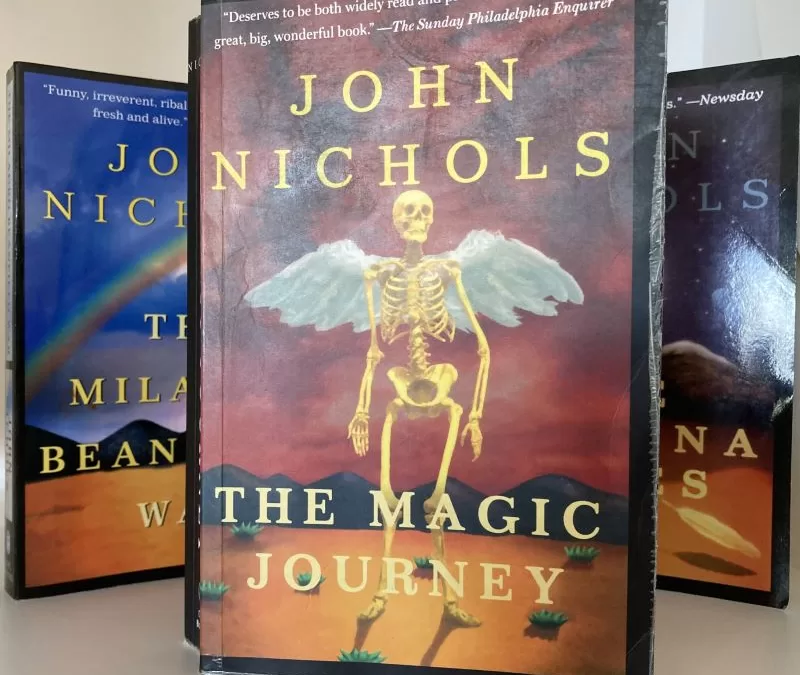

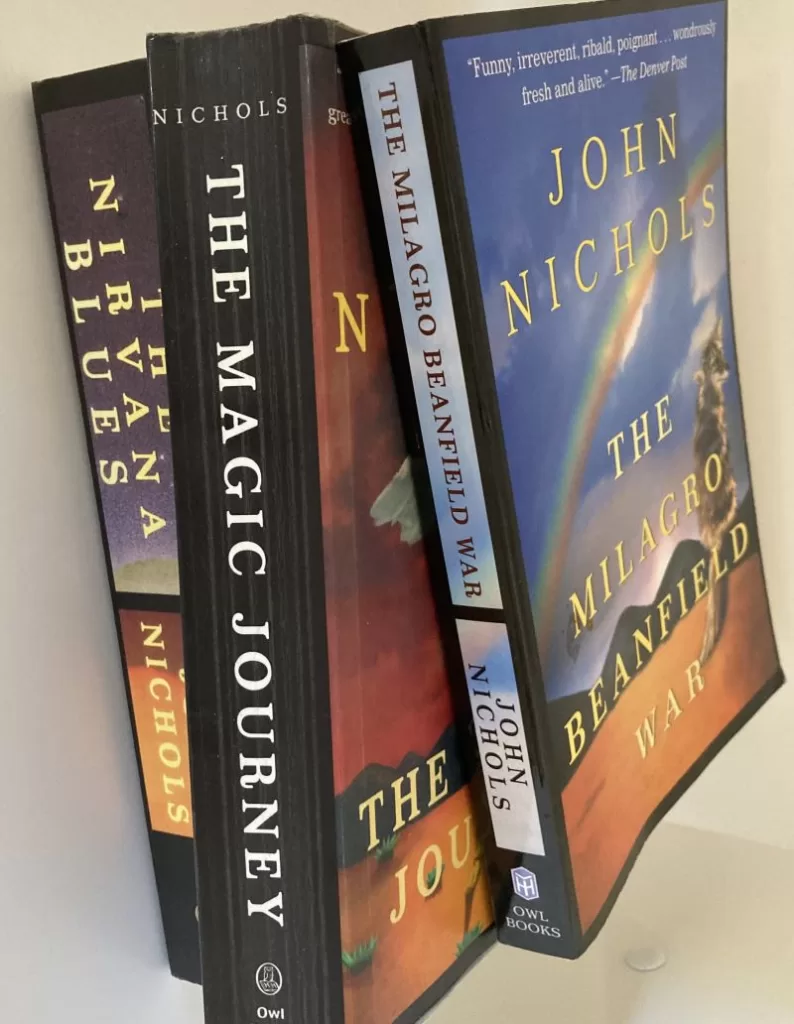

In the fictional town of Chamisaville in the Southwestern United States, during the Great Depression of the 1930s, Cipriano García—stark naked save for a pair of boots on his feet and a rose in his hand—stood next to the crater as ashy debris settled to the ground all around him after the bus loaded with stolen dynamite had exploded four feet away. The detonation, “had leveled everything else within a half-mile radius” yet there he stood, “unscratched by a dynamite blast.” So begins The Magic Journey (1978) by John Nichols, the ostensible prequel to The Milagro Beanfield War (1974) and the second of what would eventually become, along with The Nirvana Blues (1981), his New Mexico Trilogy.

The “miracle” of Cipi García inspired some enterprising out-of-towners—including Rodey McQueen whose mysterious bus had exploded —to erect the Holy Chapel of the Dynamite Virgin. Within eight days of Cipi surviving with only his boots and a rose, this now-holy site was “[l]ocated at the exact center of the still sizzling crater,” as Nichols writes, “and garnished on either side by the large pools of recently discovered mineral waters casting a theatrical mist across the scene…” The rest, as they say, is history, because, as someone more recently said, “If you build it, they will come.”

I recently puttered through Colorado and into northern New Mexico mainly along US Highway 285, avoiding the freeway as I am prone to do. I camped in the remotest of places in my 20 year-old Chinook motorhome while reading The Magic Journey. I enjoyed John Nichols’ socio-cultural commentary delivered with humor and more than a few crude and coarsely drawn rough edges. The book became a prism of sorts, turning the New Mexico light ever so slightly but with a pronounced and dramatic effect.

I drove into Taos, New Mexico (Nichols’ Chamisaville?) and parked. While walking through the old town area, I dropped in and out of shops as other tourists do; indeed, as I have done before in previous seasons. I ate my lunch on an outdoor patio with others like me, watching others like us stroll by. Traveling alone left me with the companionship of my own thoughts, taking in the bent light and pondering how this delightfully comfortable place came to be this place.

I have always known New Mexico as “The Land of Enchantment.” The boredom of long-ago family road trips was offset by the race to identify license plates and, for a time, my grandparents lived in Albuquerque where almost all the plates let us know we were lucky to be there. While assuming that this official state nickname referred to the enchanting landscape of a sparsely populated state, and it certainly does, I recently discovered that this moniker was also inspired by those who think and operate like John Nichols’ Rodey McQueen. “The Land Of Enchantment” was used by New Mexico’s Tourist Bureau in 1935 and added to license plates in 1941; just about the time Cipi García survived the dynamite blast.*

While at first only a few dollars were generated by the Cipi García Miracle—offering “retablos… depict[ing] the Our Lady of the Dynamite Virgin blessing a kneeling, naked, and downright contrite Cipi García”—the metaphorical die had been cast. The first coins handed over for these devotional paintings had flipped an entrepreneurial switch that would blind many who could never accustom themselves to the new bright light of American capitalism.

Organized by Rodey and a few of his like-minded friends, who came to be known as the Anglo Axis, a thoroughly corrupt yet perfectly legal plot was organized. The dynamite survival miracle was promoted to attract visitors. The road into town was paved to bring in outsiders with money (white people). Small farmers were lured away into cash-paying jobs in a growing tourist economy. Property taxes were levied on their increasingly valuable land while they were forced to take out mortgages to pay their tax bill or sell off pieces of their property to raise the money to survive. Using the legal system set up by those with the most influence (money) and soon property was moving from Chicano and Indian hands into white ones.

Four decades after the dynamite miracle, Chamisaville (Taos?) had largely abandoned its agricultural ways and adopted a cash-based economy which favored all but those without cash; which, for the most part, were the families who had staked out a largely cash-free existence on this land for centuries. A sad cultural milestone for this transformation is seen—or ignored as these things often go—with the appearance of “Chamisaville’s first homeless public drunk.”

The local resistance to this moral and cultural calamity is Virgil Leyba, an aging Mexican revolutionary-turned lawyer who futilely represents his people caught up in the legal machinations of the Anglo Axis; and April McQueen, the progressive, spirited, and rebellious daughter of Rodey who returns to Chamisaville after romping around the world to restart El Clarἱn, a small newspaper dedicated to fighting against these injustices with words.

Unfortunately, their cause appears absolutely hopeless. As April asks fitfully, and Nichols echoes several times throughout his book, “Sooner or later all political power comes from the barrel of a gun, qué no?” Suffice to say that the opening scene is not the only violence in The Magic Journey.

While the storyline is tragic, the characters we meet along the way in a number of long passages weave a lovely tapestry of a simple culture unencumbered by outside forces. Unfortunately these remembrances are overcome by invaders who have appropriated that culture for their own purposes.

In one scene, Nichols writes about a white artist drawn to northern New Mexico in order to experience an awakening of the spirit during the fretful 1970s. He describes the artist at work, painting the scene of a painter painting a beautiful portrait of a “noble Indian” complete with all the adornments that glorify his existence. In the background we see that the “model” for this portrait-within-a-portrait is a bedraggled, downtrodden, sun-weathered Native American who has lost most of his teeth.

And several more decades after that scene was imagined by John Nichols, the invasion now complete, I sat at my table on the café’s patio, doing my part to contribute to the cash-economy of Taos, and wondered about the manner in which our history is so often shaped by those with money. Sometimes, though, a writer like John Nichols comes along to reorient the light so that we can more clearly see how things really are… or, at least, properly imagine how they once were.

About a mile from the tourist area of Taos, I wound through a trailer park where appliances and other clutter dotted the deteriorating landscape. Despite seeing a stranger drive through their poor neighborhood, the few people I encountered here were friendly; waving as I went by.

Further from town, I passed through the secluded hills on the outskirts of Taos. There, I was struck by the preponderance of “No Trespassing” and “Beware of the Dog” signs, the locked gates, the high barricades, the security cameras, and the snarls of a few residents who seemed to know all they cared to know about me by virtue of the small recreational vehicle I was driving. The irony, of course, is that they were clearly sending me the message that I did not belong here

I’ll leave it to your imagination to determine who exactly was living in that trailer park and who was living behind all those fences except to say that no prism was necessary to see vividly the prescience and heartbreak of John Nichols’ wonderful book.