They are called the Chumash. The name refers to a group of related languages and dialects, but it has become the de facto title for the people who spoke them and who lived along the California coast from San Simeon to Topanga for as long as 10,000 years, before being nearly obliterated by genocide during the Spanish mission period. It remains the name applied to present day Chumash people, because despite a campaign to erase this culture, the Chumash continue to endure, and they, together with other Indigenous Californians, are working not only to recover their culture, history, and languages, but also to reclaim a voice in the decision-making process for their ancestral lands.

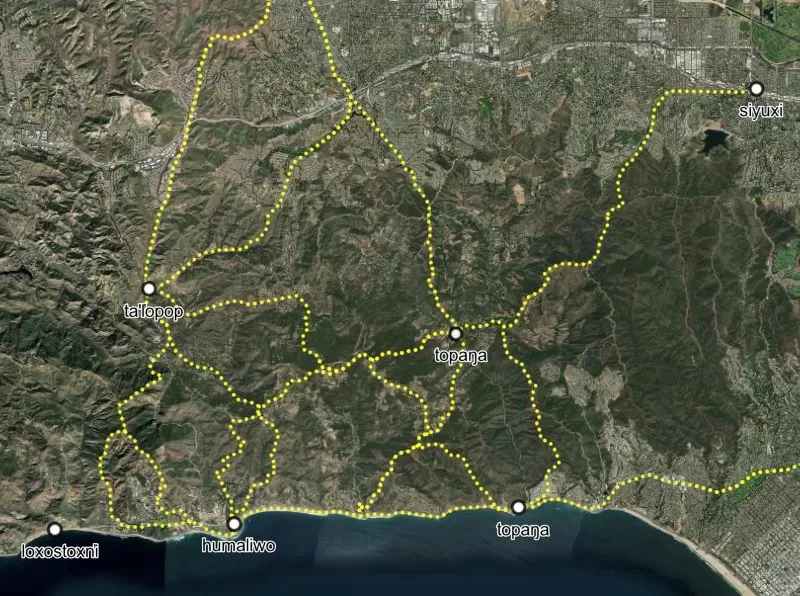

Mapping Los Angeles Landscape History, an extensive project to recover the Indigenous history of Los Angeles, released its final report on October 9—Indigenous History Day. This massive research project involved analyzing historical maps and topographic data to determine more than 15 million points, in an effort to reconstruct features that include the locations of towns, trade and travel routes, streams, watersheds, plant and animal distribution, foods and material culture, and even marriage and familial connections between different communities that in many places have been almost completely obliterated by urban development.

It’s a groundbreaking study, and its creators are continuing the painstaking task of filling in a map that was almost completely erased. Four of this project’s co-principal investigators are members of the Indigenous peoples of the Los Angeles Basin—Kizh-Gabrieleño, Tataviam, and Chumash. They worked together with historians, biologists, and computer mapping experts at USC, UCLA and Cal State Northridge, Los Angeles and Long Beach state universities. The project even drew on the skills of undergraduate students at ACCELCRAFT Institute of Geoinformatics Technology, a technical school that specializes in cutting-edge computer mapping, located in Dwarka, New Delhi, India.

“This project is unique because a commonly shared, detailed map of the historical ecology—the flora, fauna, hydrology, and landforms, that evolved within Southern California’s Mediterranean climate over millennia and supported human populations for 9,000 years, has never been developed,” the authors of the study state in the introduction. “Individually and cumulatively, the results of this research are vital resources to all regional and local planning efforts involving sustainability, habitat restoration, and preparing for climate change.”

The report also takes a new look at surviving place names. Some of the discussions on the names and the languages that they are derived from are available on video on the report’s website, as are pronunciation guides. The data presented challenges some long-held assumptions about what some of these names actually mean.

It is part of local tradition that the name Topanga means “the place above,” or sometimes “where the mountains meet the sea.” The source? State Parks documents state that, “Tongva and Chumash speakers who were interviewed in the early 1900s, [said that] Tupá’nga or topá’nga is the word for Topanga in the Ventureño Chumash language and it means “point that the mountain range, which ends there, in the sea.”

The Mapping Los Angeles History report suggests instead that the name comes from “topa,” a species of wild cane that may have grow by the Topanga lagoon, before it was bulldozed to make way for the highway:

“Top(a) is our native cane grass (Phragmites australis subsp. americanus) a relative of the southern arundo, [an invasive non-native plant] which has had a negative effect on the top(a) population.”

The report also details trade routes through the canyon, and the communities aligned with Topanga through marriage ties, placing it among the other major Chumash towns, including Humaliwo, and not the neighboring Gabrieliño communities to the east.

The city of Malibu has embraced the theory that its name, based on the Chumash community of Humaliwo, means “where the surf sounds,” or “where the surf sounds loudly.” That definition appears in federal, state and local government documents. It’s written into the city’s official history as an incontrovertible fact. However, the Mapping Project report concludes that there is no way to know what the name—pronounced huma-LI-woo, not hoo-ma-li-wu—actually means.

I spoke with Matthew Vestulo, who works in the field of Indigenous language and cultural revitalization, and contributed his knowledge of and research on Chumash place names and their significance for the project.

“There is a lot of misleading information,” he told me. “A lot is inferred and implied, or glossed over.” [Early researchers] were more concerned with filling in the blanks.”

Vestulo theorizes that the root for Topanga is the same as that for the Topa Topa mountains near Ojai. The wild cane it refers to may have grown in the Topanga Lagoon, when it was a lagoon—before the Pacific Coast Highway was constructed.

The name of a village in the heart of the Santa Monica Mountains may also provide a record of a plant community that is now extinct: katsekhenen, in the heart of Malibu Canyon, means “the pine.” Remnant populations of conifer habitat, left behind when cooler, wetter the Ice Age ten thousand years ago, do continue to survive in other parts in the coast ranges, including near Santa Barbara. Was that also the case in the Santa Monica Mountains? The name of this ancient village suggests it was.

Vestulo also discussed the possible origins of the name Malibu. He explained that “[The verb] ‘iwo’ suggests a place of sound, but that he can find nothing in the word Humaliwo that suggests ‘where the surf sounds all the time,’” Vestulo added that Zuma—Sumo—usually defined as meaning “abundance” is more likely to have derived its name from a root word meaning “water” but that, as with the name Malibu, no one really knows.

“I was told by an elder, ‘whatever holes we have in understanding, we don’t fill in with supposition,” he said. “It’s important to pass down questions.”

Humaliwo is only one of several Spanish, Mexican and Anglo efforts to spell the Chumash place name. A 1967 paper authored by Alan K. Brown entitled “The Aboriginal Population of the Santa Barbara Channel” gives an assortment of other name variants including “Jumaliguo”, “Humaliu”, “Oumaliu”, “Umalibo”, and “Malago.”

The name was officially simplified to “Malibu” by the Spanish colonial government when the entire 13,300-acre area was awarded as the Topanga, Malibu, Sequit land grant to retired soldier Jose Tapia in 1805, but it continued to be described as “Malago” or “Malaga” on maps and in the rare occasional newspaper story throughout the nineteenth century.

Brown states that in 1957, language researcher Madison Beeler, working with a contemporary Barbarano source, derived the spelling “malíwu,” and suggested the etymology hu-“over there” and wu, “the surf sounds.”

It was only a suggestion, but it was quickly adopted and has gone unchallenged. Vestulo describes it as part of a false narrative that was more easily adopted than dispelled. Some of these myths are gradually being addressed, like the message children were taught in California public schools as recently as the 1980s that the Chumash were extinct—not true. This is a living culture and a living people.

One of Vestulo’s main goals is keeping the languages of the Chumash people alive.

“Mapping the place names is invaluable,” he said.

Sharing that knowledge is also key. “Non-native people benefit from knowledge,” Vestulo said.”The more they know about the land, the more love they feel for it.”

All of the data presented in the report carries with it a sharp reminder of how little we actually know about the culturally diverse people who lived in what we call Los Angeles for more than 10,000 years, and the landscape they lived in.

The process of recovering that history and restoring the people who made it and their descendants to visibility is an ongoing effort. This remarkable research project is a step towards mapping not only the past, but also the way forward.

“The natural landscape of Los Angeles supports all Angelenos. Our beaches and mountains, oceans and rivers, grasses and trees, coyotes, pumas, and birds surround us and provide us with beauty and resources for living” the report states. “Before the arrival of Spanish settlers to Los Angeles, Indigenous peoples of what is now Los Angeles County cared for the natural world—the trees, flower fields, scrublands, wetlands, estuaries, and the fisheries—using fire management, cultivation, tending, and pruning for over 10,000 years. In other words, the so-called “natural” landscape of Los Angeles that we appreciate today was shaped by a thousand generations of Native peoples. The healthy condition of this ecology was an “Indigenous landscape…Indigenous ecology and the Indigenous peoples who never ceded these landscapes nor ceased to care for them.” Mapping Los Angeles Landscape History: The Indigenous Landscape can be viewed at lalandscapehistory.org/2023-final-report/. Everyone who lives in a location on the map should take the time to take a look. Its authors hope that it will provide: “a resource to help us look into the ancient past of our natural world, and to support our collective efforts to better care for it, to restore it where possible, and to plan for a more sustainable future.”

Am born & raised in So. CA. And became familiar with Topanga, & Malibu during my late teens. I was born & raised to the East of L.A. I have such happy memories of Topanga during the 60’s . It was full of wonderful music, peaceful happy folks, & psychedelics. A beautifully green area, of So. California. I Wasn’t lucky enough to live in Topanga during a long career in the L.A. Fashion Industry. ( a 47 yr. Career ) I’m feeling so blessed to be living here & supporting, ALL that is Topanga. First hand, feet planted. In this very, calming area, of So. CA. Cherishing my teen memories again, first hand & living the grandparents dream, of living close to my family members. I’m looking forward to many, many years, here with nature, once again. And the future of : Mother Fox Jewelry … I am the Artist & my daughter Tiberon Tramblie, manages this, my small business 🫶

Wonderful article! Thank you for covering this important new information.