When I told Aunt Maddie that I wanted to take piano lessons she didn’t tell me it was sissy, the way my father would have. She smiled. “Good idea,” she said. “We need to find you an instrument.”

That wasn’t so easy. Piano makers, like so many other manufacturers, were focused on the war effort—in this case, airplane parts and coffins, we learned, and a new piano would be expensive, even if we could get one. I couldn’t ask my aunt for something like that.

It was Aunt Maddie’s friend Alice Browning who turned up a second-hand instrument that was for sale. It had been left behind by neighbors who had no intention of returning to their Malibu beach house as long as there was the risk of an enemy attack on the coast.

⬥⬥⬥⬥⬥

Mrs Browning was a busy lady. She volunteered with the Women’s Emergency Unit and the Red Cross. She was always looking for people to provide entertainment, activities, and meals for the soldiers stationed in Malibu, or organizing paper and metal drives, or teaching first aid skills and how to knit bandages.

The fearless Jessie lived in mortal terror of her, ever since she took that first aid class for an article in the Coastwatchers newsletter.

“I’d rather die than try to knit another bandage,” she told me savagely. “And her husband is really creepy. He made movies about vampires and ghosts and circus sideshows and he was once in the circus himself—he was a magician, you know, the sawing ladies in half and vanishing cabinet kind. He’s kind of a weird recluse who never comes out of their house. Some people think he’s mad.”

I wasn’t afraid of Mrs Browning. I thought she was nice, and I couldn’t imagine her living with a madman—she was so sensible and kind.

Like her husband, she had been in movies, too. She was an actress back when movies were silent. Now she just mostly did things for the war effort. Sometimes she was maybe a little too enthusiastic, like the time she told Mr Zelle she wanted his prized 1910 electric Durocar for the scrap drive.

“It doesn’t run,” she told him. “It would be much more useful if it was melted down to help our soldiers.”

“It will run, Madam,” Mr Zelle replied. ‘And it will also burn, not melt, because it is mostly made of wood.”

Other old cars were not so lucky. Mr Zelle shook his head in dismay as a neighbor’s old Duesenberg was hauled away, but at my aunt’s ranch Mrs. Browning had to be content with an old iron plow that was rusting away out by the horse barn.

I guess I’m lucky she didn’t want the piano for the scrap drive. There’s a lot of metal inside—strings and a metal frame. I knew because Mr Zelle had let me look inside his grand piano, and showed me how the strings are struck by little hammers when you play the keys.

⬥⬥⬥⬥⬥

Mrs Browning drove up in the Red Cross ambulance the day after calling to announce she had found us a piano.

“Where’s the emergency?” Aunt Maddie asked.

“I have the piano for you, my dears,” Mrs Browning announced. She sounded jubilant. “No one was in need of first aid today,” she explained. “And the ambulance was the only thing I could get a hold of that was big enough to transport a piano. The boys on patrol at the beach helped me load it in. They’re such dears. One of them plays the piano himself. I told him he could come up and give it a try when he’s not on duty, and he could be so helpful, teaching James how to play. I know you won’t mind, Maddie, dear, and it would be so nice for him to have the opportunity. Perhaps some of the other men would like to come, too. They have so little entertainment and they work so hard, poor dears.”

Poor Aunt Maddie. It sounded like the piano was going to come with strings attached, and not just the musical kind. If she was bothered about suddenly becoming part of Mrs Browning’s plan to entertain the troops she didn’t show it, and I was too excited to think much about it. I think if it was a live pony I wouldn’t have been more excited.

Mr Calzada came over to help. The piano was wrapped in army blankets. There was no way to see what it looked like, but I could tell it was an upright piano instead of a grand piano like Mr Zelle’s. That made it easier to move, but it was still about the size of a small horse. Between the four of us we were able to get it out of the ambulance and into the house.

“I don’t know if it’s a good one, but it sounds good enough to me, and I’m sure it will do for now,” Mrs Browning said, pulling off the blankets.

My aunt was looking at the gold lettering on the right side of the cover over the keys. It spelled out the name “Bösendorfer.”

“The people who sold it were happy to let it go because they think it sounds German,” Mrs Browning said. “But you’re too sensible to care about that.”

“It’s American now, in any case, and it’s an Austrian company, not German,” Aunt Maddie said. “It’s a very fine instrument, just the thing for James, but it’s worth far more than they are asking.”

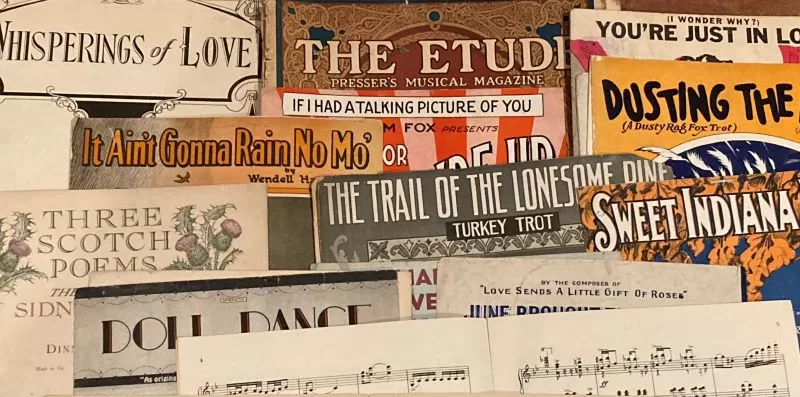

Mrs Browning shrugged. “They weren’t using it, and it’s an old instrument.” She smiled at me and handed me a paper parcel. That’s the music that came with it. It’s all from the 1920s. I’ll expect you to learn to play it all for us, James, then your aunt and I can show you how to dance the Charleston.”

Aunt Maddie wrote two checks: one for twenty-five dollars to the people who were selling the piano, a second for the same amount to Mrs Browning’s Women’s Emergency Unit.

When Mrs Browning had gone we shuffled the furniture in the living room to make room for the piano opposite the fireplace. It looked very grand and aristocratic, even if the black finish was a bit scuffed and dusty.

I tried playing a few notes. It was out of tune, but it sounded wonderful to me. I felt overwhelmed with gratitude. Not only had Aunt Maddie not laughed when I told her I wanted to take music lessons, she had found me a piano and paid a lot of money for it. I tried to offer her the five dollars my father sent me, but she wouldn’t take it.

“Save that for something your father would approve of,” she said. “Although, you might find he doesn’t object to music as much as you think he does.”

“But how can I ever pay you back?” I asked, dismayed.

“By following your heart and learning to play,” she told me. “If it makes you feel better, it is a very good instrument. Whoever bought it in the first place probably paid a hundred times more for it back in the 1920s. If you take good care of it, you’ll still be playing it when you are an old man.”

That made me laugh. “I didn’t realize it was like adopting a pet, a parrot maybe—they live for a really long time.”

“Well, see to it you take good care of your new pet,” she said, giving me a grin and a hug.

⬥⬥⬥⬥⬥

That was how the Bösendorfer came into my life. Aunt Maddie found a piano tuner, and Mr Zelle volunteered to teach me. I learned a lot from him, struggling with scales and arpeggios—I didn’t mind the hard work. To me it sounded beautiful, like water flowing, or it did when I learned enough to play smoothly.

I also learned a lot from the Coast Guard ensign—his name was Bob Henry—who came to play the piano on Saturday afternoons when he wasn’t on duty, and from his friends who came with him. Some of them brought harmonicas or ukuleles, others would sing along. Aunt Maddie honored Mrs Browning’s suggestion and made them all welcome. If she minded the weekly invasion, or my endless hours of practice, she never let it show. I soon found I had a pretty good ear for music and was able to pick out almost any tune. Learning to read music was harder, but I worked hard on it all summer, and in learning the language of music I felt like I had been given a magic key. That those small, tadpole-like symbols could hold an entire symphony was a revelation—play each note the way it was inscribed and the music would come alive, no matter how long ago it was written. But it wasn’t just an introspective revelation. Music was a way of reaching out to other people. Through it I made new friends, and was able to step out of the shadow cast by my father’s expectations for me. I began to have my own expectations for myself as a person, not just an extension of someone else. It was a good feeling. When I played, my worries for my father, and my sister, and for Kitty and her family, receded—at least for a time—and I could focus just on the music. Mr Zelle had told me that the piano had the power to transform ideas and feelings into music, but it also transformed the person who played it.