Every winter brings king tides to the California coast—some of the highest and lowest tides of the year. King tide isn’t a scientific term, but it has become a popular way to refer to the astronomical high tides that occur around Christmas—hence the term “king” for what is a powerful alignment of the gravitational pull between the sun, the moon, and the Earth.

High king tides raise the risk of coastal flooding, but they are also accompanied by correspondingly low tides. Unlike summer minus tides, these winter lows occur in daylight hours—usually in the afternoon—offering beachcombers and naturalists an extraordinary opportunity to explore the usually unseen world of the intertidal zone.

This is a strange and wonderful biome, weirder than anything that appears in science fiction movies. Its home to giant sea slugs that release clouds of purple ink, octopuses that can change their shape and color to match their environment, ancient colonial animals that come together to create insatiable colonies of stinging tentacles, dragon-like fish with poisonous spines, and ancient gastropods that can live for decades and change their sex from male to female as they mature.

NOAA defines intertidal zones as existing, “anywhere the ocean meets the land.” That definition encompasses a vast variety of ecosystems, from sandy beaches to precipitous rocky cliffs, from mudflats to shingle and rocks.

Tidal zones are divided into four physical divisions: The spray zone is the area above the high tide line that is only submerged during the highest tides or strongest storms. This is usually the domain of shorebirds and the sand-dwelling animals they prey on, including isopods and amphipods—the lively “sand fleas” that get their name from its ability to jump, but which are’t related to terrestrial fleas.

In winter, the spray zone provides a place for overwintering seabirds to gather and rest. Look for unusual visitors like black skimmers and oyster catchers among the usual suspects, which include California brown pelicans; Western, California, ring-billed, and Heermann’s gulls; and elegant and royal terns. The boundary between the spray zone and the high intertidal zone is the place to look for tide wrack, including colorful seaweed, driftwood, shells, the outgrown exoskeletons or lobsters and crabs, dead fish, and even deep sea planktonic animals like medusa jellies, by-the-wind-sailors, and salps—transparent tunicates that resemble clear glass. This flotsam is a sort of all-you-can-eat buffet for gulls and opportunistic crows. On the more remote stretches of the local coast it’s been known to attract larger foragers, including coyotes and gray foxes.

After a storm, one might also encounter “drift seeds,” among the tide wrack—hard seed pods or nuts that can be carried thousands of miles by the Pacific currents, washing up far from the trees that produced them. Less welcome is the vast quantity of plastic jetsam that also washes up with the natural wrack—from children’s toys to cigarette lighters. Natural wrack is vitally important for a host of animals, providing food, forage and shelter. Beaches that are “groomed” to remove wrack for the convenience of humans have far less biodiversity than those that are left undisturbed.

The high intertidal zone lies next to the beach. It’s exposed twice a day during all but the slackest tides, exposing its inhabitants to the sun air for long stretches of time. This intertidal zone is one of the toughest environments on earth. The plants and animals that live here have evolved a wide range of coping skills to adapt to constant change, long periods of exposure to air and low oxygen levels, turbulent wave action and shifting sands, and predation that can come from above or below. On rocky beaches this zone is home to familiar tide pool and rock dwellers like anemones, chitons, mussels, gooseneck barnacles, hermit crabs, and limpets. On sandy beaches, this zone is inhabited by sand crabs and mollusks like the tiny bean clam and the purple olive snail. These species provide essential food for shore birds, including sanderlings, willets, curlews, godwits, plovers, pipers, and whimbrels. At local sandy beaches in late summer and early autumn, stingrays, leopard sharks and dogfish come in on the tide to feed in the shallow water on those same food sources.

The middle intertidal zone is also revealed twice a day. On rocky shorelines this zone is rich in biodiversity. It tends to have deeper pools that offer its inhabitants more safety. Animals found in the middle zone include sea stars, black turban snails, shore crabs, sea hares, sand worms (no, not the species from Dune, the tiny kind that build colonies out of sand) and octopuses. Tide pool sculpin, a tough and adaptable fish, make their home here, often living their entire lives in a single tide pool. This species can breathe through its skin, surviving for up to 24 hours in shallow pools with low oxygen levels. This zone is also a nursery for many species that begin life as planktonic animals.

The low intertidal zone is only revealed during the lowest low tides, like the ones that occur during king tides. The creatures and plants that live in this zone have more protection not just from rocks but from kelp and marine plants like sea grass. One is more likely to encounter fish in the low intertidal zone, and some of the less frequently seen species like giant green anemones, kelp crabs, and even the occasional abalone—once abundant, now vanishingly rare. This is also home to the giant wavy turban snail, which produces one of the largest shells found on our coast.

Beyond the low intertidal zone is the pelagic, the open ocean zone that is home to free-swimming species like dolphins, sharks, sea turtles, and a host of fish species.

Not every beach offers rocky habitat, but the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area is home to some fantastically diverse and unspoiled tide pool habitat, including Point Dume State Marine Reserve, Leo Carrillo State Beach, Malibu Lagoon State Beach and Topanga State Beach. The intertidal zone at these beaches is a window into an endlessly rich and strange world.

The most sustainable approach to exploring tide pools is with a camera or sketchpad. All living marine organisms are protected at state beaches and many of the things that live here are fragile and easily harmed or killed. We are visitors in the lives of animals whose existence is a constant struggle for survival. It is important to keep interactions to a minimum, and to watch where one puts one’s feet.

Anemones, sand worms, and other rock-dwelling organisms are fragile, but they aren’t the only things at risk. This is a potentially hazardous place for humans, too. Rocks are not always as stable as they look and algae can be incredibly slippery. The volcanic rock that forms the backbone of the reefs and tidepools at many local beaches can have sharp edges, and so can animals like barnacles. It’s also important to keep an eye on the tide and the waves. Sneaker waves can sweep the unwary off their feet, and the tide has a way of catching up with tide poolers—spending too much time on the rocks can result in challenges getting back to dry land.

Apps can offer instant ID gratification, but sometimes an old school field guide is a better bet, especially for those who wish to learn more than just a name. Spotting something unusual is a thrill, but even the most common tide pool animals are remarkable and worth a second look. Tide pools and the wonders they hold are one of the great pleasures of a winter beach day. This is a mysterious and alien world that is right on our doorstep.

The next king tide is February 9, with a mighty 6.86-foot high tide at 8:15 a.m., and an impressive negative 1.67-foot tide at 3:20 pm. The afternoons from February 7 February 11 will also have minus tides.

Ochre Sea Star, Pisaster ochraceu. The ochre star is making a comeback on the local coast, after a close call with extinction from a viral disease. This member of the echinoderm family is extremely strong, preying on mussels and limpets, which they engulf with their “arms,” and pull open with their numerous “feet.”

Ochre stars have no brains, but operate instead on a ring of nerves that control the action of the arms, or rays. This is a keystone species that is vital for the health of the intertidal zone. It’s one of the main predators of the California mussel (Mytilus californianus), and helps to keep this abundant shellfish from taking over. Ochre stars themselves have few predators, but gulls will go after smaller specimens, prying them off the rocks and swallowing them whole.

Although they are named for the color ochre, this sea star can be orange, purple, red, or brown.

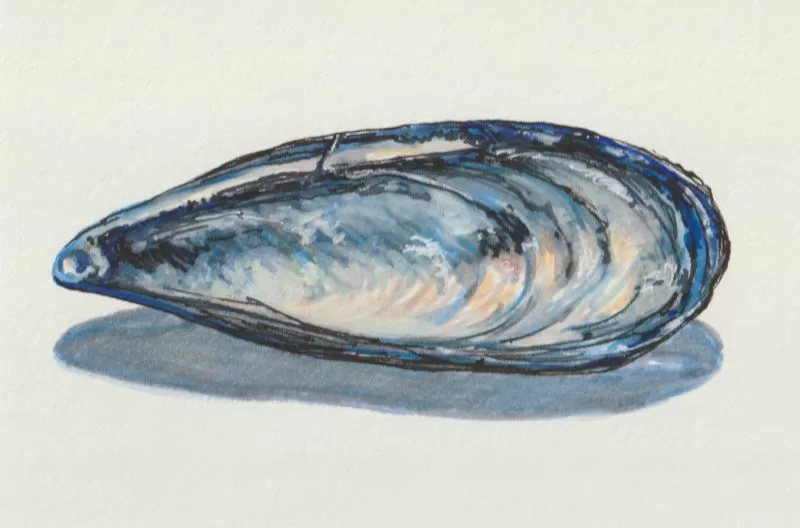

California mussel, Mytilus californianus So ubiquitous that it rarely receives a second thought—unless it’s on the menu, the California mussel is an amazing animal. This bivalve uses its hard shell to protect itself from the elements and from predators during hours spent in the open air. It uses filaments of incredibly tough cement called byssal threads to anchor itself to the rocks and to its neighbors in the mussel colony. According to the Monterey Aquarium, the California mussel can filter up to three liters of water an hour, using fine hairs to trap plankton. This mussel species can survive in punishing conditions, and can tolerate more pollution than many other species, but it comes at a cost. The mussel, and it’s beautiful, blue shell, can contain elevated levels of toxic chemicals and heavy metals. That makes this species a sort of “canary in the coal mine.” A 2013 study by the San Francisco Estuary Institute, which has monitored contaminant levels in mussels since 1977, found that there is “clear evidence of significant regional declines in many contaminants that caused serious water quality problems in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s,” including declines in the concentrations of the pesticide DDT, “forever chemicals” like PCBs, tributyltin—a highly toxic chemical used to prevent the growth of marine organisms on the hulls of ships, and heavy metals, including lead, and silver.

“These declines occurred in response to bans on the use of these chemicals, along with improved wastewater treatment and source control. Other contaminants whose emissions have not been reduced have not shown comparable declines,” the report found.

The flower-like starburst anemone, or sunburst anemone—Anthopleura sola—is a remarkable member of the phylum Cnidaria. Individuals can reportedly live for more than a hundred years, and this animal can reproduce sexually, by releasing eggs and sperm, or asexually, by splitting in two and cloning itself.

The anemone’s beautiful blue and green coloring is due to symbiotic relationship with algae or planktonic animals that live in the anemone’s tissues.

Although they appear fragile, anemone are tough and adaptable, able to survive in the high intertidal zone and in water that has high levels of contaminants. Starburst anemones uses powerful stinging cells—nematocysts—to defend against predators, and use camouflage to disguise themselves during low tide, gluing on bits of shell and other flotsam to disguise their exterior, and pulling their tentacles inside to protect themselves from exposure to the sun and air.

The brown sea hare, Aplysia Californica, can grow to be impressively large for a slug, often measuring more than 15 inches from nose to tail. It gets its name from appendages that suggest a rabbit’s ears but are actually scent organs. When the tide is in it is a graceful swimmer. During low tides it often finds itself stranded on the beach or in exposed tide pools, unable to move when its body is out of the water. The sea hare’s thick, viscous skin enables it to retain moisture. This species has an even bigger cousin, A. vaccaria, which can grow to be more than three feet long and weigh as much as 30 pounds. The black sea hare also turns up in the intertidal zone during low tides, but it is less common than its smaller relative. Both species are toxic to most potential predators. The brown sea hare is able to produce an acrid purple dye as a last defense. The black sea hare relies on its tough skin and toxic chemicals to keep predators away. Both species are preyed on by lobsters, the garbage crew of the ocean.

Tegula funebralis, the black turban snail or black tegula, is a common sight in local tidepools. This medium-sized marine sea snail has been on the menu for Coastal Indigenous people, including the Chumash, for 12,000 years. It’s also an essential food source for gulls, octopuses, sea stars and crabs. In 1971, this humble sea snail was found to have a new sense organ, a tiny pouch, called a bursicle, that contains powerful chemoreceptors that work like a highly specialized nose to detect the presence of potential predators and enable the snail to turn tail and run—as fast as its single foot will carry it. It must be effective, because turban snails that evade predation can live for as long as three decades. Black turban shells are a favorite with hermit crabs, who move in when the original owner has moved out.

Unlike the vegetarian black turban snail, Callianax biplicata, the purple olive or olivella snail is a voracious predator. These small snails are responsible for the maze-like network of trails that appear in the sand at low tide. They prey on smaller mollusks but also eat carrion, and they are preyed on in turn by moon snails and shore birds. Olive shells can be purple, white, brown or even orange.

The Chumash name for this species is “anchum”, and beads made from the shells served as currency and were traded widely. Archeologist Lynn Gamble has studied Chumash culture since the 1970s. She writes that shell beads have been manufactured for over 10,000 years in California, and that they were traded far from the coast where they were made. “Through sleuthing, measurements and comparison of standardizations among the different bead types, it became clear that these were probably money beads and occurred much earlier than we previously thought.”

She also states that the Chumash and their neighbors had a complex system of commerce that was facilitated by shell money, much of it made from purple olive shells. When olive shells turn up in tide pools, instead of on the sandy sea floor, they are usually being repurposed as homes for hermit crabs.

Like olive shells, sand dollars live in the sandy sea floor, usually in the low intertidal zone. The species native to the West Coast rejoices in the name Dendraster excentricus—the eccentric sand dollar. It’s called a sea cake, and biscuit urchin. Sand dollars are suspension feeders that prey on plankton and other microfauna. Their shells are favorites with beachcombers but the live animals are rarely seen.

The chestnut cowrie, Neobernaya spadicea, is the only surviving member of the family Cypraeidae on the California coast, and its range is limited to the south and central coast, from Monterey to Baja. That wasn’t always the case. The fossil record preserves the cowrie’s 22 extinct relatives dating from the Jurassic to the Miocene. The shell of the trivia snail looks like a cowrie but is actually more closely related to the Velutindae. There are two species on the California coast. The larger Solander’s trivia shell, Trivia solandri, which is only found on the Southern California coast, and the smaller, darker, California coffee bean, Trivia californica, which occurs from the Bay area, south.