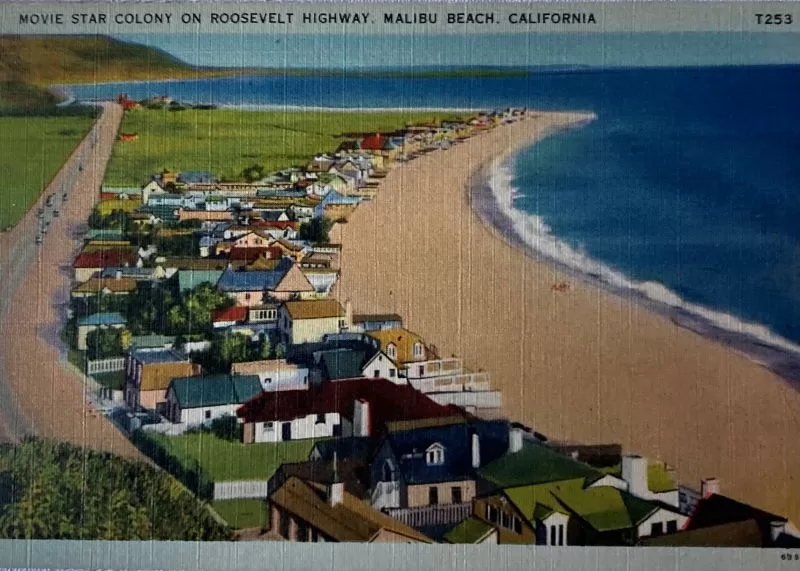

The Malibu Beach Colony got its start in 1926 as a tiny strip of bungalows by the side of the sea. It quickly became the Malibu Movie Colony, a refuge from Hollywood for Hollywood names and faces. By 1928 it was wall-to-wall houses, each one occupying a 30-foot-wide lot that was leased from May Knight Rindge, the sole owner of the 17,000-acre Malibu Rancho, for $30 a month on a 10-year lease.

May Rindge was reluctant to part with any part of her ranch, but she needed the money to help defray the cost of litigation over the state’s plan to build what ultimately became Pacific Coast Highway on her property. The price tag for the decades-long legal fight was estimated at $20 million.

May won an earlier battle with Southern Pacific Railroad over a train route in Malibu—that’s why the tracks turn inland at Oxnard and run through the San Fernando Valley to Los Angeles, instead of along the coast. But she couldn’t prevail against the county and the state over a highway. During that fight she faced not only government lawsuits, but the newly powerful Southern California Automobile Club lobby, and public opinion was against her. May lost the battle in 1926, the same year she began selling leases at the Malibu Colony.

The Supreme Court decision allowed the highway to be built across her land. The county, anticipating victory, had already paved portions of the route leading up to the rancho. Previously, the road was little more than a rough track that often ran on the wet sand and made for hours-long trips, now it was a “modern” two-lane highway.

“The coast road started at Las Flores and, in 1926, came as far as Malibu Canyon,” wrote local historian Glen Howell, in 2005. “That really opened up Malibu to easy travel.”

It made Malibu an ideal destination for the newly rich Hollywood set: easy to access, but remote enough to be private. Beach houses financed by film industry money were already going up along the coast in Santa Monica and Pacific Palisades.

The strip of coast at La Costa, on the easternmost edge of May’s private kingdom, was subdivided for a romantic fantasy-Spanish-Colonial-revival-themed housing development and placed on the market. The sandy beach that would become the Colony was different. It was near the land May planned to give her daughter Rhoda, and Rhoda’s husband Merritt Adamson, for a Malibu house of their own, and it was visible from the hill where she planned to build a grand Moorish-style mansion for herself—now the Serra Retreat—overlooking the Malibu Lagoon.

May didn’t want permanent neighbors at the site of the Colony. She would lease the land for ten years and require that all structures be temporary—easily removed when the leases were up. By limiting the size of the lots to just 30 feet wide, May hoped to limit the size of the houses. As an ardent supporter of prohibition, she also included a clause that stated that “lessees must not consume liquor.”

Finding anyone willing to pay $30 a month for a 30-foot-wide patch of sand—approximately $6,000 today—might have seemed like a challenge, but Realtors Dave Duncan and Art Jones, hired to undertake the task, approached their contacts in the thriving new Hollywood film community and quickly found takers.

Despite the peculiar terms of the lease agreement, there was no shortage of applicants. The combination of beach and privacy was a powerful lure. Fame was already impacting the lives of the first generation of film celebrities. The Hollywood Chamber of Commerce, which was using the new industry to promote tourism, published the first map of “the houses of the stars.”

Silent era leading man Douglas Fairbanks provided an inadvertent thrill for a group of elderly female voyeurs who broke into his backyard in Beverly Hills at the right moment to observe him taking a morning swim in his pool, au natural. On another occasion, his wife, actress and producer Mary Pickford, recounted looking out her window to find an entrepreneur with a pushcart selling hotdogs to a busload of tourists eager to see “the houses of the stars.”

Cowboy superstar Tom Mix found the attention amusing, and put his name in lights on the roof of his Catalina retreat. Leading lady Gloria Swanson was less amused. She sold her home in Los Angeles, frustrated that there was no way to keep the public out. She was one of many celebrities who found the privacy of the Malibu Colony a welcome change.

Some accounts say Swedish-born cinema star Anna Q. Nilsson was the first to sign a lease; others, the handsome and eccentric actor Richard Dix. Either way, there was soon a building boom, as Hollywood names vied for their own patch of sand.

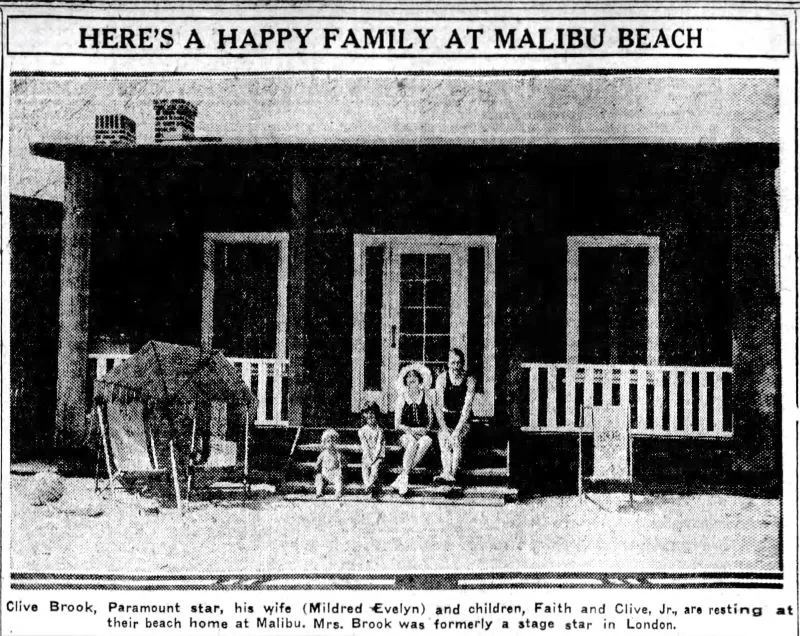

Nilsson and Dix were soon joined by actors Ronald Colman; John Gilbert; Adolph Menjous; Kenneth Harlan; Clive Brooks; Ernest Torrences; Neil Hamilton, Warner Baxter, and directors Raoul Walsh, Herbert Brenon, Allan Dwan and Gregory Lacava. Gloria Swanson snapped up three lots; Mary Pickford and her husband Douglas Fairbanks snaffled 10, according to the gossip column in the November 19, 1927 Star Weekly.

One of the most remarkable things about the colony is how many of the original lessees were single women. The early years of the film industry, before the studio system took over, offered an unprecedented opportunity for women to build a successful career. Throughout much of the country, women only won the right to purchase property in 1900, and in many places still could not get a mortgage without a male co-signer as recently as 1974. The first generation of successful Hollywood actresses, screenwriters, and filmmakers had the financial freedom to do what they wished, and if they wanted to lease 30 feet of sand on the strand in Malibu and build a beach house, they didn’t have to ask anyone’s permission.

Female residents of the Colony included “bathing beauty” Marie Prevost; former child star Bebe Daniels; silent era superstar Gloria Swanson; Alice Joyce—known as “the Madonna of the Screen; “It Girl” Clara Bow; “triple threat” Virginia Bruce; Delores del Rio—Hollywood’s first major Mexican-American film star; actress and aviatrix Ruth Chatterton; vaudevillian-turned-leading-lady Lila Lee; and Constance Bennett, star of stage, film, radio, and decades later, television. By 1930, the list included rising stars Myrna Loy, Barbara Stanwyck, and Joan Crawford.

Most of the cottages were only occupied on weekends. Dix and director Herbert Brenon were among the first to live at the Colony full time. They were joined by comedian Karl Dane who designed and built his angular Nordic-style home himself, and director Allan Dwan, who often worked with Dix, and who served as the Colony’s honorary mayor.

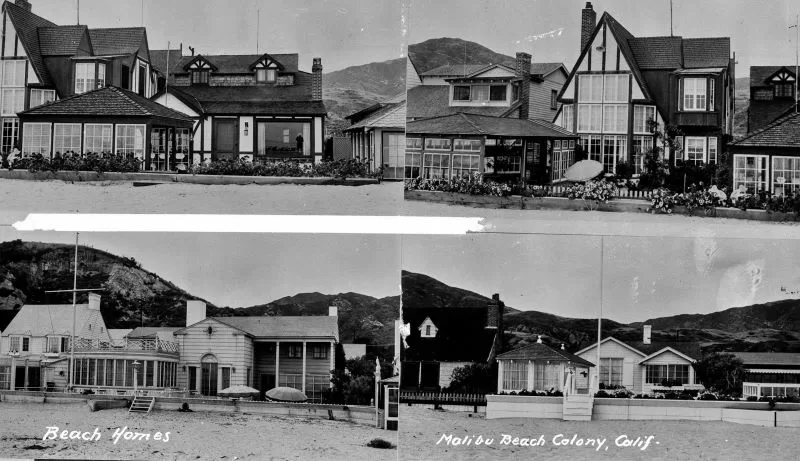

Each cottage reflected the owner’s taste. The buildings were meant to be temporary and the builders ran wild with a mad mix of styles and themes that suggested movie sets. Many were built by studio set builders using inexpensive studio lumber. Some were named for the film projects that funded them. Herbert Brenon, who directed the successful 1924 version of Peter Pan, named his Malibu Colony bungalow “Peter Pan Cottage.” “Beau Geste,” was the cottage of screenwriter and script doctor Elizabeth Meehan who wrote the screenplay for the film of the same same name. Scottish character actor Neil Hamilton, who starred in Beau Geste with Colony neighbor Ronald Colman, named his sailboat The Digby, after his character in the movie. Hamilton also starred in The Great Gatsby, scripted by Elizabeth Meehan and directed by Brenon, and he was a longtime friend and frequent co-star of Bebe Daniels, whose cottage was a few doors down from his.

Hollywood was a close-knit industry in the 1920s. The people who occupied the row of beach houses socialized with each other but they also knew each other professionally. Charlie Chaplin played tennis with Mary Pickford at the Colony—the two had co-founded United Artists with Pickford’s husband Douglas Fairbanks and producer D.W. Griffith and were among the most powerful people in Hollywood. Chaplin also played ping pong with Gloria Swanson on Raoul Walsh’s porch. Walsh directed Chaplin at the beginning of his career in the 1915 film The Regeneration, and would go on to direct Swanson at the height of her fame in the 1928 film Sadie Thompson.

One can’t help speculating that the lease on 30 feet of sand in the Malibu Colony was desirable not just because of the privacy and beauty of the location, but because it provided a unique business opportunity to network. The Malibu Beach Colony soon became known as the Malibu Movie Colony, although detractors called it the “Rich Man’s Hooverville.” By 1928 there were 50 cottages, and fabulous sums of money were reportedly offered for subleases.

A 1928 feature in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle proclaims the residents of the colony “fugitives from fame,” before ironically describing each house in painstaking detail and explaining exactly who lived where. However, the public was actively discouraged from attempting to sightsee by guards patrolling the private road and the beach—the Coastal Act which ensures public access to the beach wouldn’t be passed for another 50 years.

“The only passport that gets you into Malibu is a personal invitation from one of the colony, properly vised [sic],” the Eagle feature boasts. “Fabulous sums for transfer of leases are turned down flat. The so-called ‘fugitives from fame’ are enjoying the greatest luxury of their cinema careers: privacy.”

The houses in the colony had electricity and water—it’s said that the water wasn’t very reliable but the supply of gin never ran dry. There were no telephones. The management employed college students to run errands, and deliver telegrams and groceries. The world was kept away.

Bebe Daniels, who started her film career as a child and lived perpetually in the spotlight, is quoted saying that at the colony she was finally free from public scrutiny. “It is wonderful to do what you please,” she said.

Some residents really did do what they pleased. During prohibition, alcohol for Colony parties was reportedly delivered by boats owned by legendary Los Angeles rum-runner Tony “The Hat” Cornero. Colony parties were famous, and occasionally ended with midnight skinny-dipping. Clara Bow, who arrived in 1928, was a powerful swimmer and liked to surf. So did rising star Myrna Loy, and leading man Ronald Colman, who learned to surf from Hawaiian Olympic swimmer Duke Kahanamoku, a regular visitor at the colony.

Society columns describe Colony residents playing tennis in a court cut out of the cow pasture, and volleyball at a net installed in front of Allan Dwan’s cottage. They also gathered at each other’s houses for picnic lunches and BBQs.

The 1928 feature story in the Brooklyn Eagle shares the details of a beach dinner at “Hal-Louise Cottage”, the beach home of comedian Louise Fazenda and her husband, Warner Brothers publicist Hal Wallis. It included “fried chicken, ham, hot biscuit, corn, butterbeans, candied sweet potatoes, cauliflower salad, ice cream and spice layer cake,” and the conversation revolved around “talking pictures, beauty recipes, and reducing methods.”

“Reducing methods” really were a major concern. The author of a piece in the July 21, 1929 Evening Star snarks that, “about the only place in Malibu where you can get a decent meal is Lousie Fazenda’s cottage. Louise never has dieted…If Irvin Cobb wants to write a sequel to his amusing ‘Speaking of Operations,’ all he has to do is steal up on a group on the beach at Malibu and listen to what they are telling the sad, starving sea gulls.”

Colony resident Joan Crawford is said to have subsisted on cold consummé and jars of mustard—the gulls probably wouldn’t have wanted to share. Clara Bow’s diet consisted of grapefruit and Melba toast, but both women enjoyed surfing. Gloria Swanson was one of the first practitioners of yoga in the Hollywood community. She was also a vegetarian and health food advocate. The Colony offered sun, surf, and space to embrace alternative lifestyles, even if it was only on the weekends.

The golden age of the colony was short. On October 26, 1929, an electrical fire at No. 83—actor John Gilbert’s cottage—rapidly spread, destroying nearly 30 homes. The fire was blamed on defective wiring.

When new structures were built, many were larger and more permanent. The fire came at the end of the silent era. The new residents of the colony were a different kind of Hollywood elite. There were some who made the transition to talkies. Ronald Colman, with his dashing good looks and distinctive English accent, was one. Richard Dix was another, although he had already moved on from the Colony, finding a more peaceful and secluded home in the hills above Las Flores Canyon, where he kept chickens, turkeys, setter dogs, and scotties. Actress Ruth Chatterton not only had a successful film career, but she became a bestselling novelist.

Movie mogul Jack Warner was one of the “new” Colony residents. So were Dracula director Tod Browning, and song and dance man Bing Crosby. They built imposing permanent houses, instead of beach shacks, building up instead of out. And when May Rindge was forced to sell the land a few years later, they were ready to buy.

The Malibu Colony has remained exclusive, expensive, and a retreat for entertainment industry luminaries. The houses, almost all of them mansions now, not bungalows, are still a mad mix of styles, each one right next to its neighbors. The road is still private, and at high tide this neighborhood becomes an island, but the beach is a public beach. At low tide, anyone can enjoy a walk past this remarkable row of houses, but the beach is different now, far narrower. Instead of having sand in their backyards, contemporary residents have decks, stairs and revetments like seawalls.

If sea level rise predictions are accurate, May Rindge will ultimately get her wish: the lease may end up being 150 years instead of 10, but the ocean—the true leaseholder—will eventually reclaim this strip of coastline and all of the houses on it. The moral of this Hollywood movie story? Nothing is permanent.