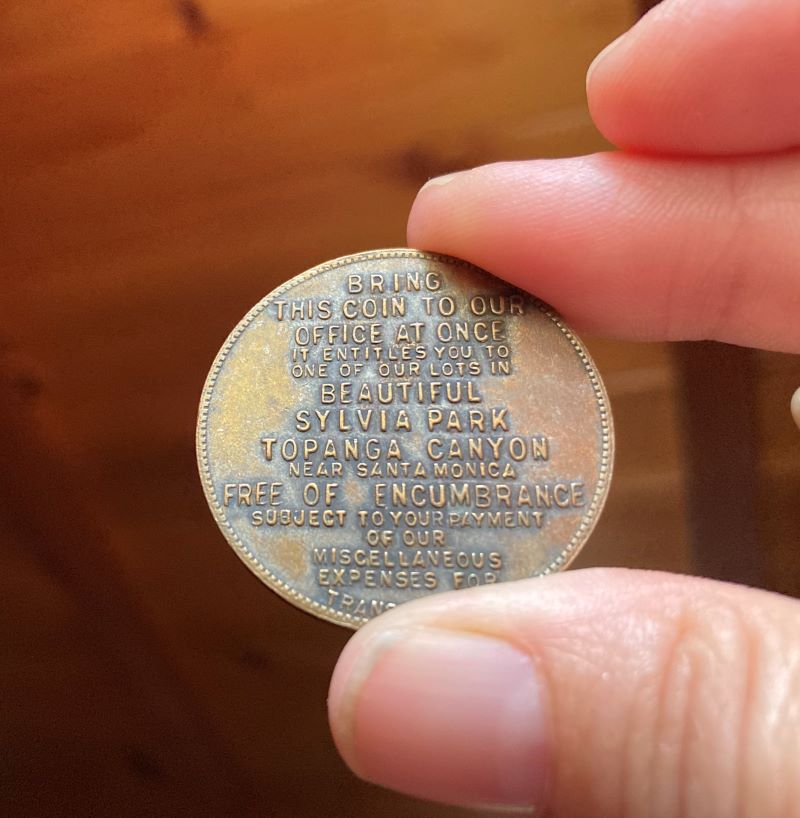

The coin is a little bigger than a quarter. It isn’t decorative, but it has a nice weight to it, and the words stamped on it remain clearly legible, even though this token was struck a hundred years ago. The token promises the holder a parcel of land in the newly created Sylvia Park development in Topanga, “free of encumbrance.” One needed only to bring the coin to the office in Downtown Los Angeles, and trade it for the deed to a small piece of terrestrial paradise. This talisman isn’t just an artifact of local Topanga history, it’s a pocket-sized reminder of the crazy, boom-or-bust real estate frenzy of the 1920s.

Whether they knew it or not at the time, the promoters of the Sylvia Ranch subdivision embraced the concept of boosterism, an idea that was big—really big—in the 1920s. The war to end all wars was over, the nation was booming, electricity, automobiles, and the transcontinental railroad were making the world a smaller, brighter place and putting far-flung and exotic places like California in reach. Real estate speculators, fueled by railroad interests, began to sell the Golden State as the ultimate paradise for health, happiness, and prosperity: a pastoral utopia, where gentleman farmers grew oranges and enjoyed a romantic, Spanish-themed fantasy lifestyle, and the only snow fell on the mountains in the background of life.

That trend peaked in the 1920s, the great decade for Spanish colonial revival architecture—all of the glamor, without the inconvenient parts like colonialism and genocide and cyclical droughts. In his book on the evolution of Los Angeles, historian and iconoclast Mike Davis wrote that the Mission Revivalism so popular during first decades of twentieth century relied upon a fictional past, one that was more closely related to the Land of Oz, with its Emerald City, than to the often brutal tragic real world history, and like the Emerald City, it was a fantasy made up of snatches of history, a liberal sprinkling of pixie dust, and a whole lot of theatrical sleight of hand.

Fantasy developments sprang up on a big scale in places like Hollywood, with its fairytale mix of architectural styles, and Venice—home to Venetian canals, complete with gondolas. Big scale developments and the imaginative advertising that promoted them inspired more modest efforts. The local mountains were soon targeted by aspiring real estate tycoons, with mixed results.

In 1924, real estate booster John Russell McCarthy wrote a whole book about it. “These Waiting Hills” is a poetic paean to urban sprawl. “Many are turning towards the Santa Monica Mountains, either for recreation or to live there, and in the firm conviction that this is a good thing…it seems to me that these hills are waiting for just such a human invasion.”

Malibu’s first real estate development, La Costa, featured fake Mission ruins in an effort to cash in on the old Rancho’s Spanish land grant history. The developer later served time at San Quentin, but he was charged with defrauding his investors using a Ponzi scheme, not false advertising.

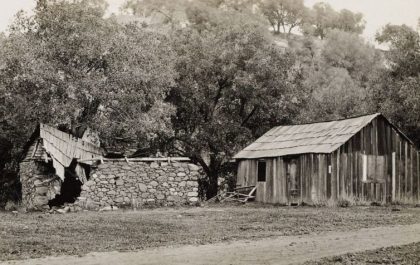

Brothers and would-be real estate tycoons Charles and Irvine Goldman set their sights on Topanga. Artists and vacationers had already discovered the canyon, but it was still mostly the domain of homesteaders, who earned a sometimes precarious living farming and ranching. Modern conveniences like running water and electricity were only just beginning to be part of the Topanga lifestyle, made possible by the expansion and paving of the canyon road in 1915.

In 1924, the same year John Russell McCarthy penned his book in praise of developing the mountain, the Goldman Brothers purchased part of the Cheney family homestead. It was a mix of agricultural acreage, oak woodland, and rugged hills. They divided it into small lots—a lot of small lots—and started advertising for buyers. One of the things that drew the Goldmans to Topanga appears to have been the promise of Mulholland Highway, which was intended to be a wide, multilane parkway instead of a narrow snake of pavement winding through the mountains in a series of hairpin turns.

Because this was the 1920s, the Goldman Brothers felt compelled to go big, or as big as they could on a small budget. They made the coin-like tokens that advertised the development and scattered them around the city (the story that they hired a plane to drop them appears to be apocryphal, and a good thing too—the tokens are heavy). They took out full page ads in the Daily News and invented dialogue to show prospective buyers how to broach the subject to a spouse or friends. “Marie, we’re going to live in the mountains this summer; I can drive to work every morning in 57 minutes or else get a cheap room and come out on weekends!” one ad enthuses.

The Goldmans priced their lots at $100— “only $15 more down and you can put your little tent or cabin up at once!” The prices were well below those in the nearby property, but the parcels were also much smaller and completely unimproved.

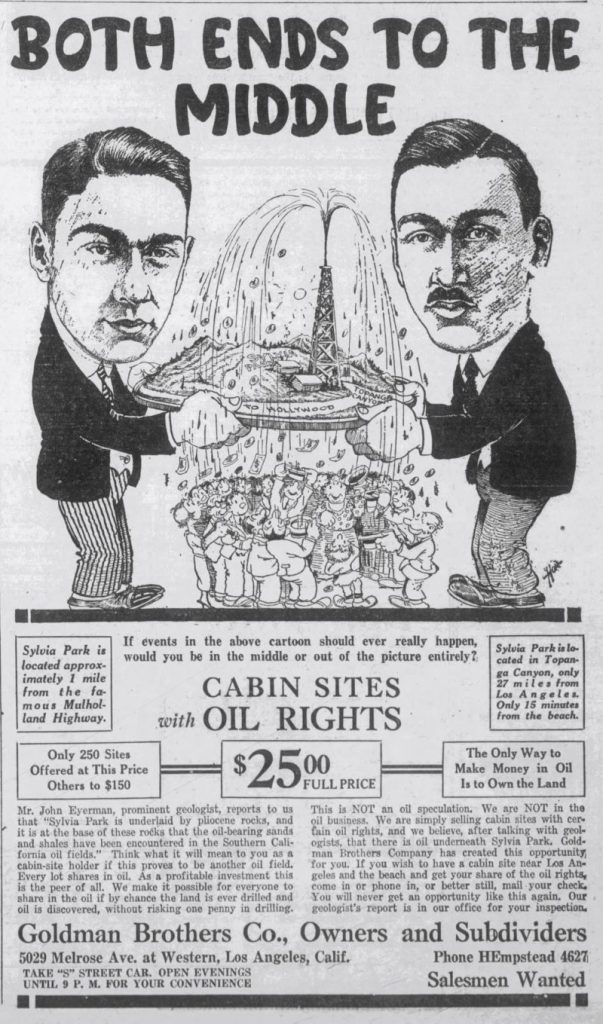

When the early ads failed to generate enough interest, the Goldman brothers advertised that everyone who bought a piece of land in the Sylvia Park development would receive the oil rights to their property.

Topanga historian Bill Buerge is the proprietor and owner of the Mountain Mermaid, formerly the Sylvia Park Country Club. He describes how the Goldman brothers published their own fake newspaper, predicting an impending oil strike and describing the potential to stick it rich.

“They even built an oil derrick,” he told me.

They did. Charles Goldman established the “Monarch Oil Corp.” and was responsible for drilling the test well, located near the intersection of what are now Sylvania and Paradise lanes. It’s still in the state’s archives, listed as a “dry hole,” one that was plugged in the late 1930s—a relief, no doubt, to current residents (not all test wells were plugged, some were abandoned). No oil was found, but the Goldman brothers struck water, which didn’t make them rich but did help facilitate development at Sylvia Park. They had to content themselves with establishing a water company instead of an oil fortune.

The Goldman brothers weren’t the only local landowners who pinned their hopes on the prospect of striking it rich during the oil mania that gripped the area in the first decades of the twentieth century. Down in Malibu, May Knight Rindge, desperately in need of funds to finance her costly legal battle with the state and county over the right of way for the coast highway, was busy drilling test wells. “Wildcat” oil derricks were springing up all over—there was one in Red Rock Canyon in Topanga (this one yielded traces of oil and gas), and another on the valley side of the Topanga Summit. Most of them turned up nothing except rock and dirt. The real value in this area would turn out to be the land itself.

The Goldman brothers’ best advertising angle wasn’t oil wells but the potential for purchasers to build a vacation home or cabin—Topanga already had a reputation as a rustic and scenic vacation destination. However, just weeks after the initial real estate offering was advertised, a quarantine was declared for the Santa Monica Mountains, in an effort to prevent the spread of a devastating outbreak of livestock disease. A photo of the coast route into Malibu from this time shows a ditch filled with some kind of chemical intended to disinfect the hooves—or tires—of anything passing through.

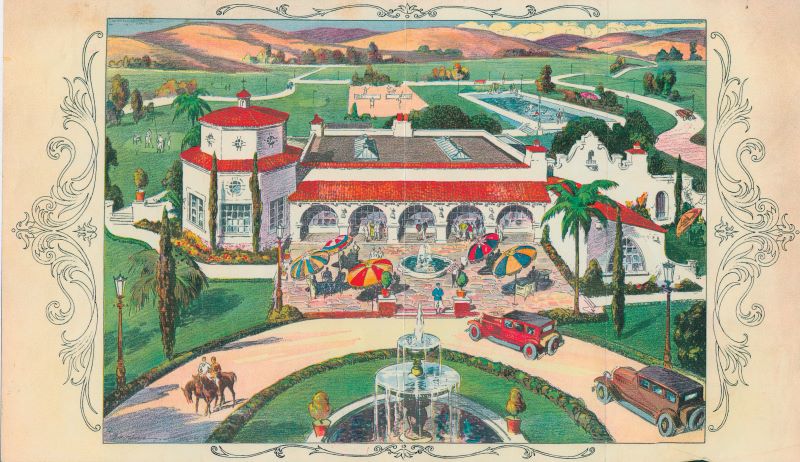

For the Goldman Brothers, the quarantine must have been a hard blow. It wouldn’t be the last, but they continued to plan. In the late 1920s they began planning an expansion. The Sylvia Park County Clubhouse would be built on a new addition to the original acreage. Purchasing a lot entitled the buyer to a membership. The elegant, Spanish Colonial style building, with its pool and lavish grounds, would be the centerpiece to the new community. Architect Charles E. Finkenbinder designed the structure, described in the Los Angeles Evening Express as, “a modern structure of Spanish type architecture.” Construction began on the $75,000 development in 1930, but the stock market crash of 1929 had already delivered a crushing blow to the 1920s real estate boom.

“Even today, we forget that when the market goes up, it goes back down,” Buerge told me.

Money was tight until WWII, when materials and manpower were in short supply. After the war, when things were looking up and a new building boom began, much of Sylvia Park burned in the devastating Topanga Fire of 1947. Tax records show that many of the lots, including some still owned by the Goldmans, were behind on taxes. Some were sold to pay the delinquent tax bills, their owners simply walked away.

The original Sylvia Park cabins and tents have been replaced by more permanent homes. Many of the tiny lots have been adjusted to make larger ones, others remain undeveloped open space—some of these, no doubt, would have been the “free” lots offered on the tokens, lots that were too small or too steep to build on. The oil derrick is a distant memory, but the Country Club—now the Mountain Mermaid—is still there. It has been a youth retreat, a gambling den, a gay nightclub, and a derelict ruin that provided stabling for goats and other livestock and was perilously close to demolition, before Buerge acquired it and restored it. It is now a historic landmark, and a perfect example of California’s optimistic, over-the-top, boosterism boom time.

“Real estate developers created much of California’s infrastructure,” Buerge told me. “We might think our communities were designed by someone with a higher calling, but it was mostly people trying to make money. Developments like this one came to a screeching halt when the bubble burst.”

Sylvia Park never became a country club development—or an oil boom town—but one thing the Goldman Brothers got right was how peaceful and beautiful this corner of the Santa Monica Mountains is.

A hundred years later, Sylvia Park remains a tranquil, rustic neighborhood, a retreat from the hectic pace of urban life. That was one claim that wasn’t an exaggeration, and it remains as true today as it was in 1924.