Our good friends Pam and Rick moved to Idaho a few years ago and we finally got around to visiting them. With our small camper in tow, we recently meandered through parts of Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and into Idaho.

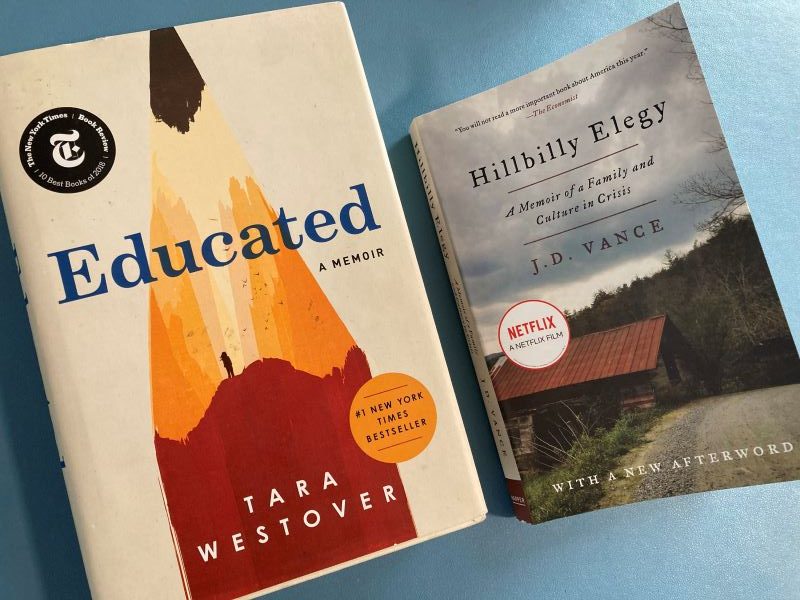

As we puttered north and west from Flaming Gorge Reservoir in Utah, Pam suggested a few sites we might visit along the way to their place on the western side of Grand Teton National Park. While her recommendations focused on outdoor recreation opportunities, she suggested that I might want to read Tara Westover’s Educated: A Memoir (2018) to “get a feel for the isolation here in Idaho…”

Reading and then writing about Idaho while traveling through Idaho seemed a great way to immerse myself in the place. After pitching the idea, it was suggested that I should also consider commenting upon another memoir, J. D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis (2014). Of course, Vance was recently selected by former president Donald Trump to be his running mate in the upcoming 2024 presidential election.

Tara Westover was raised in southeastern Idaho to Mormon parents that spent a great deal of energy preparing for the End of Times. Her father saw the government as evil and sought to protect his children from society’s corrupting influences including schools, hospitals, and even the organized aspects of their religion.

Hillbilly Elegy is a story of the current plight of formerly working-class whites left behind due to economic globalization and the exodus of American factory jobs. J. D. Vance grew up in Appalachian southeastern Kentucky and in Middletown, Ohio. His grandparents moved to Ohio along with many other “hillbillies” seeking work during the post-World War II economic boom. Frequent visits to Kentucky helped to maintain the hillbilly culture that Vance celebrates. Unfortunately, that culture has been economically devastated and is now a Culture in Crisis.

These are not politically-oriented books except to the degree that they both explore the social and cultural landscape that has given rise to Trumpism. Kentucky and Idaho have been reliably Red states throughout the twenty-first century while Ohio has become Red since the emergence of Donald Trump. This is the line that runs directly through these two fascinating stories; understanding that Westover and Vance grew up in wildly different environments which, by their very nature, are not known to the vast majority of us. And, if we are to ever move beyond the current state of divisiveness in this country, I believe it will require understanding these other Americans and, most importantly, how they came to admire or reject a demagogue.

J. D. Vance’s candidacy for national office should go a long way to doing just that as he undergoes the scrutiny leveled at someone who hopes to become our next vice president. Given his youth and the advanced age of his running mate, the next few months may signal an enduring turn in our national history. I believe that reading his book, among other things, will help make sense of all this as we move forward.

Vance describes his community’s “distinctive embrace of cultural tradition [including] an intense sense of loyalty, a fierce dedication to family and country… We do not like outsiders or people who are different from us, whether the difference lies in how they look, how they act, or, most important, how they talk.”

While Vance describes these latter characteristics as some of the “bad traits” of his people, it is difficult to imagine that, from what we have seen so far, these traits have not continued to shape his views.

He was also taught early on “to challenge scientists on the theory of evolution. I learned about millennialist prophecy,” he writes, “and convinced myself that the world would end in 2007. I even threw away my Black Sabbath CDs. Dad’s church encouraged all of this because it doubted the wisdom of secular science and the morality of secular music.”

In the late 1990s, during the birth of cable news, Vance embraced the conservative argument that there was a “war on Christmas.” “I had an acute sense that the walls were closing in on ‘real’ Christians,” he wrote. He read a book “about the various ways that Christians were discriminated against. The Internet was abuzz with talk of New York art displays that featured images of Christ or the Virgin Mary covered in feces. For the first time in my life, I felt like a persecuted minority.”

These sentiments seem to ring true with current Republican opposition to DEI—Diversity, Equity and Inclusion—programs and “woke” ideology that encourages sensitivity to our social, cultural, and racial differences.

Seeming to speak directly to the origin of our current state of affairs, Vance writes that, “All of this talk about Christians who weren’t Christian enough, secularists indoctrinating our youth, art exhibits insulting our faith, and persecution by the elites made the world a scary and foreign place.”

Vance’s celebration of hillbilly culture belies the trajectory of his own life. If you were to look at only his first seventeen years, you would find yourself scratching your head that he is only one election and one heartbeat away from arguably being the most powerful single person on the planet. After four years in the United States Marines, Vance embraced self-discipline to earn a Bachelor’s degree from Ohio State University in Columbus. He then went on to graduate from Yale Law School in 2013.

Oddly, these later experiences seem to offer much less insight into his current political positions—opposing abortion, LBGTQ rights, same-sex marriage, and gun control—than those aspects of his days growing up with his Kentucky family in Ohio: within a culture riddled with violence and addiction. Raised primarily by his grandparents, Vance’s commitment to these traditions seems to reach back to a 1950s sensibility; making him a perfect fit for those hoping to “Make America Great Again.”

Most recently, it has been revealed that Vance may have some darker motives. An On Point Podcast, “JD Vance and the Rise of the ‘New Right,’” a production of WBUR in Boston, the VP contender is quoted as saying in 2021: “There’s this guy, Curtis Yarvin. Who’s written about some of these things. A lot of concerns that said we should deconstruct the administrative state. We should basically eliminate the administrative state. And I’m sympathetic to that project. But another option is that we should just seize the administrative state for our own purposes. [Italics mine]”* (You might want to read that again.)

In contrast, Tara Westover’s experiences see her gradually realizing the toxic nature of the environment in which she was raised: violent, misogynistic, and dedicated to the preparation for the end of the world. Much of the trauma Westover experienced was at the hands of her psychologically and physically abusive older brother Shawn. “The first time I wore lip gloss,” she writes, “Shawn said I was a whore.”

As the abuse is piled on, and her parents refuse to believe her reports of it, Westover begins to deeply question herself. After one incident she recalls, “It was not that I had done something wrong so much as that I existed in the wrong way. There was something impure in the fact of my being.”

Hers is a story of conflict over her commitment to family while slowly learning that there is a larger world out there that bears little resemblance to the images conjured by the biblically-inspired harangues of her father and the abuses of her brother. Her other brother, Tyler, who had been to college and serves as an inspiration, teaches Westover how to read. As her curiosity is piqued, she clamors to get her hands on whatever books she can find… and hide them from her overbearing and suspicious father.

As she reads, her entire world view is transformed. “The skill I was learning,” she writes, “was a crucial one, the patience to read things I could not yet understand.” She eventually discovers that while her father speaks with a fallacious certainty that comes hand in hand with his rabid faith, the actual world is filled with those seeking knowledge and exploring the mysteries of the universe.

By 17, the largely self-taught Westover learned enough to be accepted into Brigham Young University as measured by the ACT (a standardized academic achievement test measuring basic knowledge in English, Reading, Math and Science). Filled with self-doubt, it was only her innate curiosity and raw intelligence that guided her through these first months in a culturally alien environment. Overcoming this doubt, and encouraged by a handful of instructors that recognized her gifts, her work at BYU earned her admission to the University of Cambridge where she earned a Master’s degree and then a PhD in intellectual history.

Her enlightenment journey was enhanced while studying the history of our country at BYU. After learning about American slavery and its abolition in the 1860s, she sees America’s story as one of moral progress and commitment to the fulfillment of her founding ideals.

However, her college history professor, Westover writes, “began to lecture on something called the civil rights movement. A date appeared on the screen: 1963. I figured there’d been a mistake. I recalled that the Emancipation Proclamation had been issued in 1863. I couldn’t account for that hundred years, so I assumed it was a typo. I copied the date into my notes with a question mark…”

Her hopeful observation about American moral progress turned to confusion and despair as she learned of Black Americans still struggling over many of the same inequalities a century later.

It wasn’t long until that same history began to touch her personally. On another slide was the date 1955 and “I realized that Mother had been four years old in 1955, and with that realization, the distance between me and Emmett Till collapsed. My proximity to this murdered boy could be measured in the lives of people I knew. The calculation was not made with reference to vast historical or geological shifts—the fall of civilizations, the erosion of mountains. It was measured in the wrinkling of human flesh. In the lines on my mother’s face.”

As it turns out, both Vance and Westover were born in the mid-1980s casting them into the generational cohort of early Millennials. They also share the distinction of having written memoirs while only in their 30s, a task typically taken up by those nearer the end of their lives. The fortunate result is that their memories of childhood and beyond are closer in time although both admit that what one remembers is not always consistent with what others recall.

In contrast, and perhaps best illuminating our differences today, one of these authors seems to lay claim to deep knowledge of how the world works; while the other approaches life with curiosity and open-mindedness. Unfortunately, only one of these worldviews leaves one able to handle challenges to old ways of thinking when confronted with new information.

And now that I write this, I wonder if my original hopeful premise—that we can understand one another to get along with one another—may be a bit ambitious.

*https://www.wbur.org/onpoint/2024/08/01/vance-trump-new-right-republican-election