Back to school. A hundred years ago in Topanga, it would have been on foot—and often barefoot—to the little, red, one-room schoolhouse by the creek in the bend of the dirt road.

Public education in California was still relatively new—and so was statehood—when the first Topanga homesteaders staked a claim in the mountains. The first public school in the state was established at Colton Hall in Monterey in 1849, the same year California became a state. The hall, which served as the regional government building, the school and the jail, was also where California’s first constitutional convention took place. Homesteaders didn’t arrive in the Santa Monica Mountains for another 30 years, despite the massive influx of immigrants from the United States generated by the 1849 gold rush propelled California’s acquisition as a state.

The U.S. government’s Land Act of 1862 set the local land rush in motion. It opened up surveyed public lands that had previously belonged to Native Americans to any homesteader willing to file a claim and pay a small fee. Claimants had five years to show that they were living on the land, and that they had made improvements that included building a 12-by-14-foot dwelling and growing crops. In 1889 the Land Office in Los Angeles began to open the last “free” lands on the West Coast, starting another land rush.

The earliest public school in the vicinity of the Santa Monica Mountains was founded in 1877 in the Conejo Valley, at what is now the corner of Westlake Blvd. and Hampshire Road.

The first wave of Topanga settlers didn’t arrive until 1880. There was already a scattering of mountain men (and women) scratching out a living from the wilderness. There are reports of hunters, trappers, Basque shepherds, hermits, cattle rustlers, smugglers and outlaws, as early as the first decade of the nineteenth century, but the Santa Monica Mountains, sandwiched between the huge old Spanish and Mexican land grants, were so rugged and remote that that they remained mostly uninhabited from the period when the Chumash and Tongva people were forced off the land and into the Mission system in the first years of the nineteenth century until the 1880s, when homesteaders began to arrive.

Not everyone who staked a claim succeeded in living off the land, but Jesus and Elena Santa Maria, the earliest Topanga homesteaders on record—1880—made a success of their Topanga farmstead. They built a wood cabin and raised a family that would grow to include 18 children

Manuela and Francisco Trujillo filed a claim in 1886. They already had two young sons when they arrived in the canyon.

Columbus Callen “Mose” Cheney and his wife Lucy arrived in 1891 and staked a claim on 160 acres. Their son Arthur was born 1894, the same year that a school district was created. It was named the Garapatos District instead of the Topanga District because many of the early homesteaders settled in the vicinity of Garapatos Creek—Santa Maria Canyon, Cheney Drive, and Greenleaf Canyon still bear their names.

Efforts were made almost at once to have a school, but there wasn’t a big enough population to officially warrant one in the early years. The first homestead families had a choice of either educating their children at home, or sending them to stay with relatives in a more populous area with schools. It wasn’t until 1894 that the state finally agreed to create a school district for the area.

Mose Cheney was appointed one of three school district directors, together with George M. Harter and Martin Allen (census data strongly suggests this is Topanga homesteader Morten Allen). The three men were “duly qualified to act” until an election could be held to officially organize the newly created school district,” according to the April 19, 1894 edition of the Los Angeles Times. The news story points out that, “Owing to the hilly character of the region, electors have from eight to ten miles to travel to cast their votes at the general elections.”

It wasn’t just a long trip, it was a dangerous one. Harter was killed in 1899 on his way into Santa Monica from Topanga. His team of horses bolted and his wagon overturned.

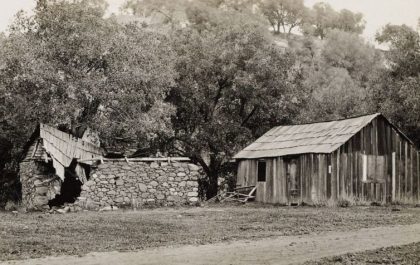

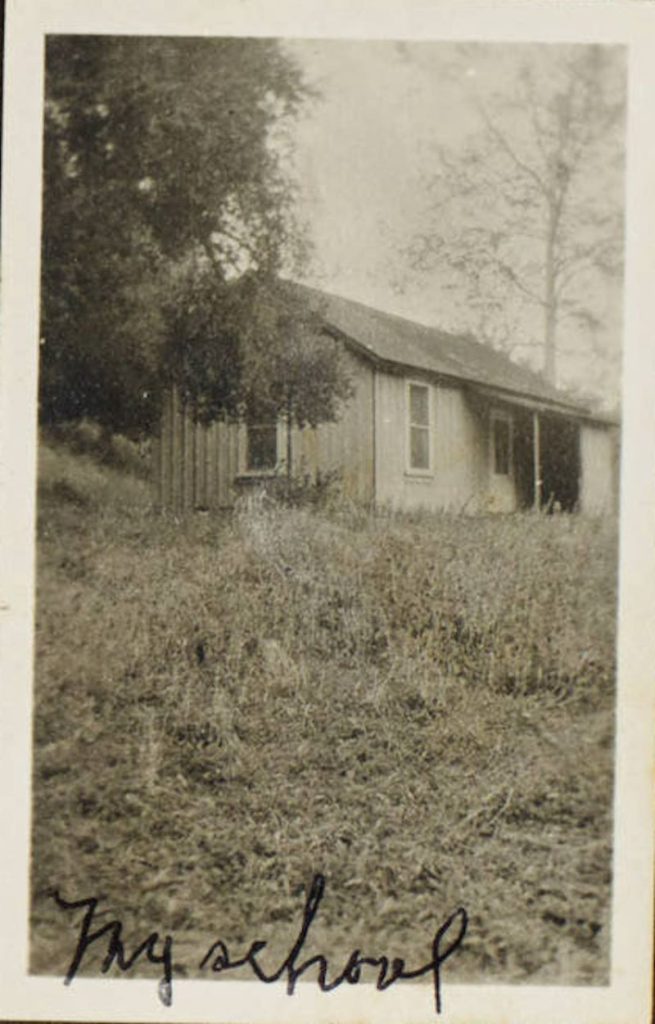

The school district was geographically large, but the school itself, when it was finally a reality, was small and not well funded. The newly established district received just $200 from the state in 1895, and often received less than $80 from the state in subsequent years. Local legend says Topanga’s little red school house began life as a barn or a shed, photos suggest that, while small and plain, it was purpose-built as a school, with ample windows, and steps up to the door. The thrifty homesteaders may have used lumber from a barn or shed to build it—getting supplied into the canyon was complicated, time-consuming and expensive.

The school appears to have opened its doors in 1893, before the school district was officially established. The remoteness of the community may have impacted efforts to find a teacher. A news item from the July 13, 1893 Los Angeles Herald listing school teacher appointments and bond allocations says, “…and the Garapatos district left out.” A teacher was finally secured for the school in September of that year, shortly before classes began. Her name was Emily Gardiner.

A 1950 article in the Topanga Journal recounts the adventures of another early Topanga teacher, Jessica Gardiner who was driven out in a horse-drawn buggy by the district superintendent just days before the start of school, when the previous teacher became ill. The road was so rough and steep that Gardiner and the superintendent had to get out and walk, picking their way on foot among the rocks and ruts, leading the horses.

The schoolhouse was lit with kerosene lamps and heated with a wood stove. There was no running water, but there were wooden outhouses—one for boys, one for girls. The schoolteacher taught all ages, from the smallest first year students to the eighth graders who might be lucky enough to go to high school in town, but more likely would be expected to leave school and go to work.

There wasn’t a bus, or even much of a road before 1915. In 1906, Calabasas residents petitioned to have their own school district. The terrain of the mountains meant a seven mile walk for those who lived on the Calabasas side of the Topanga Canyon—far more than even the heartiest students could walk. A few children rode to school, but most walked. Homesteader families expected their children to do a day’s worth of chores in addition to going to school. The day often started early, with cows and goats to milk, stalls to muck out, and livestock to feed.

Topanga was already a vacation destination by the time the community needed a school, but the tourists and summer people did not figure into the lives of the homesteaders except as a possible source of income. Town people came to hunt and fish, families stayed at camps and cabins, wealthy Angelenos built summer homes, but their children went to school in town.

Summer visitors attended dances, picnics, barbecues, and hunting parties at camps and cabins in the canyon—the Cheneys catered to the hunting crowd, offering venison barbeques, Stella MacAllister, the widow of a retired courtroom clerk and the sister of the Mort Allen who probably served as one of the district’s first school directors) ran a boarding house for visitors and served home cooked meals. She also provided room and board for the school’s teacher. The number of houses in Topanga continued to grow, as the automobile made access to the canyon easier, but the school district struggled to maintain enough students to keep the schoolhouse open in the early years. Despite that, the little red schoolhouse provided a meeting place for local families.

A 1907 feature in the Los Angeles Times authored by Cloudsley Johns, describes monthly gatherings in the little building, where neighbors gathered on “the Thursday night when the moon was fullest” to enjoy a congenial evening of music and homegrown entertainment. “The dwellers in the canyon gather in the Garapatos schoolhouse to show what each can do to amuse the others,” Johns wrote, adding that the moonlight was necessary to ensure that participants could find their way safely home in the dark.

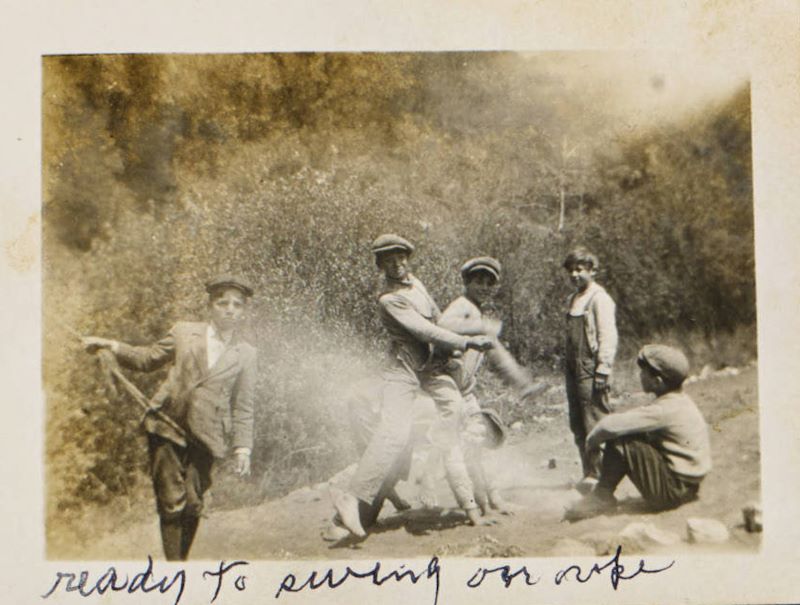

There is little information on the early years of the school or the first canyon teacher, other than her name, but we know a lot about what life was like in the canyon and at the school 20 years later, thanks to Theresa Sletton, the Topanga schoolteacher from 1912-1918.

Louise York, the primary author of the Topanga Historical Society’s encyclopedic book The Topanga Story, wrote extensively about the school. She quotes Sletton about her life there. “I taught all grades,” Sletton told her. “We started at nine o’ clock and were out at four…I really think the little school did more and better teaching than any of the large city schools. We didn’t have so many little odds and ends things to do, but we sure taught reading, writing and arithmetic.

Sletton, just out of school herself when she came to Topanga, wasn’t that much older than her students. She was adventurous, energetic, and an enthusiastic amateur photographer. She documented her life in the canyon in the early years of the twentieth century. Sletton’s candid portraits of her neighbors and her students provide a vivid look into the lives of the homesteaders. She also chronicles a time of transition, as the automobile and the roads built to accommodate it, began changing the landscape and the people of Topanga.

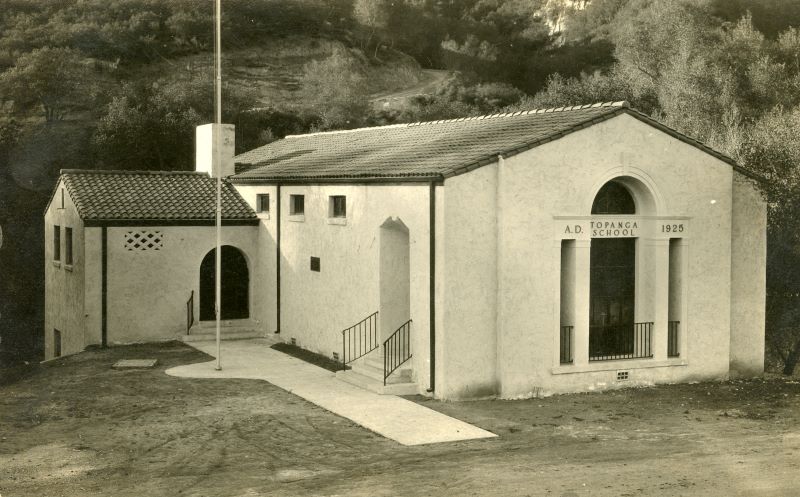

There were eight children in Sletton’s class in 1916. By 1924, the Little Red Schoolhouse was finally outgrown. In 1925, the school moved to the building that now houses Froggy’s. The new school had electricity, running water, a little library, and a lot more room, but it wasn’t enough.

After World War II, the school spilled down the hill, into the classrooms that are now part of Rosewood. TNT’s office is located in a classroom where the postwar generation learned to read and write. The public school, having outgrown even this addition, moved to its current home, not far from where the original wooden schoolhouse stood at the bottom of Greenleaf Canyon. Topanga was annexed to the Los Angeles Unified School District in 1961, during the canyon’s biggest population boom.

The Garapatos Schoolhouse wasn’t the first one-room-school in this area, and it wasn’t the last. The Decker School, which served students in western Malibu and the Yerba Buena District, was in use until 1955, when Juan Cabrillo School opened in the newly created development of Malibu Park.

Just like the settler families, high school students still have to travel into town for school, and just like the first homesteaders, many Topanga families also homeschool their children. Not many contemporary children are expected to rise with the sun and milk the cows, but a certain amount of that pioneering spirit is still alive in the canyon.