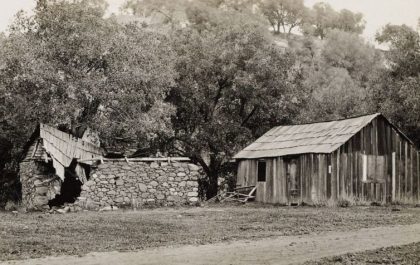

The first anniversary of the bombing of Pearl Harbor came and went with no end in sight for the war. December in California wasn’t anything like the way it was back in Illinois. I knew it wasn’t likely to snow, but I was surprised that it never even got cold enough for frost. It was hard to imagine that it was almost Christmas when it was 76 degrees outside and the sun was shining. I knew we were lucky. We had plenty of honey from the ranch bees, and milk and even butter from the goats, and oranges from the orchard, but rationing made holiday treats like candy and fruit scarce for most people. The government encouraged everyone to buy Victory Bonds instead of gifts, and to “make do, or do without.”

Despite the shortages, Aunt Maddie and I sent care packages to Kitty and her family. Kitty never complained but I knew that everyone at that camp was always cold that winter and that they missed ordinary comforts that the rest of us took for granted, even with rationing.

We also sent care packages to Aly, and my father, and even to Aunt Charlotte. Things began to arrive for us, too, although Aunt Charlotte’s gift would probably turn out to be socks.

“What’s wrong with socks?” Aunt Maddie said. “If you leave one out on Christmas Eve old Saint Nick might just fill it with goodies, you know.”

I wanted to give something really good to Aunt Maddie. With help from Mr Calzada I made a hat band for her favorite hat, the black felt one she always wore around the ranch. I made the band out of hair from the tails of all of the horses—it didn’t hurt them because tail hairs always come out when you groom them. Cosmo’s strands were red, Ariel’s white, and Monkey’s black. Braiding it took ages, and I kept losing track of the pattern and having to undo all my work and start over, but it was worth it when it was done. Woven together, the strands made a pattern a little like the stripes on the brightly-colored kingsnakes that we often saw in the garden. I thought Aunt Maddie would like that.

Remembering how much the key to his room had meant to Jacob, I made a keychain for him out of horsehair too, and then bracelets for Aly and Kitty. By then I was getting pretty good at it. Aly’s had a stripy pattern a little like a zebra, Kitty’s was especially pretty, because it had a blue glass bead woven into it. I’d found the bead at the beach. Aunt Maddie said blue beads were good luck, and that in places like Egypt people carried them to avert ill fortune. I figured Kitty could use a little extra luck.

There wasn’t any point in making a bracelet for Jessie—she would never wear it—but I’d found the perfect gift for her on the beach after a rainstorm. It was an Indian arrowhead—a really good one, made from shiny dark rock, and as complete and sharp as if it had just been made. I knew Mr Calzada didn’t approve of digging artifacts out of the ground, but this one felt like a real gift. It washed up almost right at my feet and the next wave would have swept it away again.

I knew exactly what I wanted to give the Calzadas. Mrs Calzada continued to teach me new words in Spanish. As I got better at understanding, she would tell me stories. She told me about the beautiful rosas blancas—white roses—that grew at her childhood home in Mexico and how Mr Calzada brought her white roses when they first met. I thought it would be easy to find a rose bush at the nursery that would look like the ones she described, but it wasn’t. It turns out that when you buy rose plants at the nursery they are just bundles of roots and twigs wrapped in damp newspaper and packed in wood shavings. Aunt Maddie assured me they would grow and bloom once they were planted, but there was no real way to know what they would look like except for the written descriptions. I chose one that was described as having “abundant, fragrant, white blooms,” and hoped for the best.

I wrote a piece of music for Mr Zelle’s gift. The type that’s called a tone poem. It was inspired by the canyon wren, a little bird whose song is a series of descending notes, like laughter. We had one in the orchard and I heard it every day during the spring, singing: “ha, ha, ha, ha, ha, tew, tew, tew.” It almost wrote itself into a piece of music. Writing that music down, and trying to make sure all of the notes and symbols were right so that someone else could play it and hear the same thing I heard in my head was the hard part.

I presented it to him after dinner on December 11. It was the last night of the Jewish holiday Hanukkah that year, and Aunt Maddie said that Mr Zelle must be missing his family especially much. I knew that the candles Mr Zelle lit every night that week were for Hanukkah. There were eight, and a ninth candle for lighting the others. He lit one candle every night at dusk. He told me that it was traditional to have them in the window so the light could shine out, but because of the black-out rule the candles had to be inside.

Aunt Maddie suggested that we invite Mr Zelle to have dinner with us that night, and she bought special pastries for dessert from a Jewish bakery in town. There was a coffee cake with chocolate and nuts, and little jam-filled cookies called rugelach.

Dinner was fun. Jacob, still usually silent around strangers, talked enthusiastically. He had got to be friends with Mr Zelle because of the Durocar. He was just as fascinated by the old car as I was when I first came to live at the ranch, and the three of us worked on it together most Sunday afternoons—it was coming along great, despite the challenge of finding parts.

After dinner, I presented the sheet of music. I felt embarrassed and self conscious, but Mr Zelle took the music to the piano without a word, and gestured for me to be seated. I played it through. I held my breath the whole time, but he smiled at me when the music ended. Then he switched places with me and played it himself.

“I am pleased and proud of how much you have learned,” Mr Zelle told me. “You are a good student and a good friend, James, and you have the makings of not just a true musician but a composer of music.”

He proceeded to take that little song apart and put it together again, showing me places it could be improved, but I didn’t mind. Mr Zelle showed me things about that simple tune that I could never have thought of, and when he played it back to me, it sounded like music, real music.

After that, Mr Zelle played a beautiful Bach partita as a thank-you to Aunt Maddie—he played it perfectly from memory. Then the two of us played part of a march by Beethoven for four hands. It was exhilarating but hard.

He embraced us all before he left. “Thank you,” he said. “You have been friends when I have never needed friends more, and family when family is far away, and I will always remember your kindness.”

I heard him whistling the notes of the canyon wren’s song as he walked back to his cottage.

“There goes a good man, James,” Aunt Maddie said.

Christmas morning was sunny and bright. Saint Nick really did fill my stocking. I was glad. My father announced when I was six that I was too old to believe in Santa Claus, but a kid couldn’t help wishing. On Christmas morning my sock was stuffed with nuts and candy, a battery flashlight, a pair of dice, a model plane, a banana, and a harmonica—a good one you could really play.

Aunt Maddie gave me stacks of wonderful sheet music and a watch, a nice one. Jacob got a watch, too—something he’d never had and always wanted. His watch was new; mine wasn’t. On the back of my watch was an inscription engraved in tiny letters. It said: “To JE from ME, Time Enough.”

“It belonged to your Uncle Jimmy,” Aunt Maddie told me. “They sent it back to me with his things after the war.”

“Did you give it to him?” I asked.

“Yes.”

“What does ‘time enough’ mean?” I asked. “He didn’t have much time, did he, because he was killed?”

“We had a tough time of it when we were young,” Aunt Maddie said. “And you can’t help wishing for things you haven’t got.” She smiled at Jacob, who nodded. He knew what that was like, too.

“Our mother used to tell us not to wish our lives away,” Aunt Maddie said. “But Dad would always say there was time enough to have those wishes come true in the future if we kept working towards them and didn’t give up. I think it was his way of saying have faith. When he was gone, Jimmy and I used to say ‘time enough’ to each other whenever things seemed impossible. Eventually things turned around. My career as a writer took off. That last Christmas we had together I got him the watch and had the jeweler engrave it. Jimmy took it to France with him. You’re right, he didn’t have much time, but he had time enough to make the world a better place while he was here. He would have wanted you to have his watch, James. The inscription is a reminder that it doesn’t matter how much time we have, it matters what we do with it.”

Those were nice surprises. The next one wasn’t. It was a telephone call from my Aunt Charlotte, and it wasn’t a merry-Christmas-sending-you-love kind of call. She was even madder than she was the time she called about Aly joining the WACS, and this time we didn’t get fair warning from my sister.

Long-distance calls were expensive and took a long time to put through, and Aunt Charlotte didn’t approve of them except for dire emergencies. The call came just as Aunt Maddie and Jacob and I were fixing breakfast. Aunt Maddie answered the phone and held the receiver away from her ear because Aunt Charlotte was coming as close to screaming as I’d ever heard her. From where I was, she sounded like an angry swarm of wasps. Jacob, who had been setting the table, muttered something about checking on the animals, and fled.

I prudently took the griddle off of the stove and covered the pancake batter, but I didn’t go. I wanted to know why she had called and what had made her so angry. I felt a wave of anxiety sweep over me like cold water.

It took a while for Aunt Maddie to calm her down enough to understand what she was saying.

It turned out that Aunt Charlotte had received a call that morning from my father, telling her that he was planning to get married again. He thought she would be pleased but she was furious. The lady was a nurse he met while he was recovering from rheumatic fever. They couldn’t be married right away, because nurses couldn’t get married while they were serving in the military, but they had gotten engaged.

Instead of congratulating Father, Aunt Charlotte announced that she was disinheriting him, and since he was now “as one who was dead to her,” and Aly was, too, she had called Aunt Maddie to vent her spleen.

Aunt Maddie let her vent. Eventually Aunt Charlotte remembered that the call was long distance and rang off.

The room was suddenly very quiet. Then Aunt Maddie began to laugh.

I stared at her in consternation. My father was getting married was all I could think, and he told Aunt Charlotte but he didn’t tell me.

“I’m sorry, James,” Aunt Maddie said. “I shouldn’t laugh, but your Aunt Charlotte reminds me of a stock character in a melodrama. She didn’t approve of your father marrying your mother, either. Just wait until your father has his first child with his new wife. All will be forgiven and she’ll never remember that she ever disinherited him.”

Another child? I was having a hard time with the idea of a stepmother. I hadn’t thought about other children.

“Father loved Mom. He always said he would never love anyone else,” I said, bewildered. “But now he does? I don’t understand.”

“Please pour us some coffee, James,” Aunt Maddie said, collapsing into a chair. “A person needs a restorative after dealing with your Aunt Charlotte.”

“Why didn’t he tell me?” I demanded, slopping coffee over the side of the cup and burning my fingers. “All that stuff about living in Hawaii after the war and he left out the most important part.”

Aunt Maddie handed me a napkin. “I don’t know any more than you do, James,” she said. “I’m sure we will, soon enough. Your father’s fiancée may be a lovely person. Remember, your Aunt Charlotte hasn’t met her either. She’s just determined to think ill of her.”

“I am, too,” I said, feeling miserable.

“I’m sorry, James,” Aunt Maddie said. “I miss your mother, too, but our grief won’t bring her back. Nothing we do will undo the past. We can only move forward. Your father is choosing a new path forward. It might be a wonderful one, and I hope for his sake and the sake of the girl he is marrying that it is, but you also have a new life that you’ve made for yourself, a good one, and you have a home here with me for as long as you want it or need it, no matter what. Now, let’s see if we can get a call through to your sister. She deserves to have the news broken to her, too, more gently I hope, and I was meaning to call her today anyway.”

It turned out that Aly hadn’t known either. She felt hurt, too. Aunt Charlotte blamed the girl, a “hussy” she had called her—it was a term that made Aunt Maddie laugh because she said it was old-fashioned. Aunt Maddie was doing her best to be diplomatic and give everyone the benefit of the doubt, but Aly was blunt.

“He’s a silly old goat,” she said.

“He’s a lonely man who has been sick and who is serving in a terrible war far from his family,” Aunt Maddie said with a sigh. “Young people aren’t the only ones who dream of happy endings. That doesn’t mean he’s not being a silly goat, but perhaps goats have dreams, too.”

“Do you dream of happy endings, Aunt Maddie?” I asked when the phone call ended.

“This is my happy ending,” my aunt said. “I have the great good fortune to be living mine.”

“What would you have done if the ranch had burned down?” I asked.

“But it didn’t,” she said. “And even if it had, well, the important thing is that everyone was—everyone is—safe, even the animals, and we are here spending Christmas together. We even got to share it with your sister and your other aunt, and that’s pretty amazing.”

“Now, go find Jacob, and let’s have breakfast,” Aunt Maddie said. “It’s Christmas, in case you forgot, and we shouldn’t give Charlotte the satisfaction of spoiling the morning for us.”