The Coastwatchers, TNT’s original fiction series set in Malibu during WWII, concludes in this issue. Our story began in December, 1941, just after the United States entered WWII, and ends on Christmas, 1942. Coastwatchers focuses on the experiences of its young protagonist, but there’s more to tell about what life was like in the local community.

Christmas 1942 was a bleak time in world history. It was the second Christmas of WWII—President Franklin Delinor Roosevelt announced that the United States was at war with Japan on December 8, 1941, but the impact of that declaration wasn’t felt right away. Christmas of 1942 was different. Millions of men had been called up to serve in the military and in war-related government jobs. It is estimated that more than 400,000 US service personnel were killed during that first year, not including more than 12,000 civilian deaths (for an in-depth look at just how precarious things were in 1942, check out TNT Historian Jimmy P. Morgan’s column on Tracy Campbell’s book The Year of Peril: America in 1942, https://topanganewtimes.com/2021/05/21/1942/ ).

In Europe, the situation was grim. According to the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum and Memorial website, 1942 began with the deportation to Auschwitz of 69,000 Jews from France and 27,000 from Slovakia. It ended with plans to evict and exterminate an estimated 50 million Slavs (Poles, Russians, Byelorussians, Ukrainians and others). On December 17, the Allies condemned the extermination of the Jewish people, but were not able to stop the mass killings.

The Allies were struggling in Europe, and losing ground in Africa. British civilians were grappling with food shortages and nightly bombings of the German Blitzkrieg. Refugees around the world had no place to go to escape the terror, hunger, and violence of the war.

Here on the West coast, more than 120,000 Japanese Americans were stripped of their constitutional rights and incarcerated in camps in places like Manzanar, forced to leave their jobs, homes and every aspect of their lives behind.

On the Pacific front, the U.S. victory at the Battle of Midway (June 3–6, 1942) would prove to be the turning point of the war in the Pacific—US forces destroyed the Japanese carrier force and prevented Japan from taking the offensive in the Pacific for the rest of the war—but at Christmas, those victories felt less important than the weight of the dead—7,100 fatalities and almost 8,000 wounded in the Pacific theater.

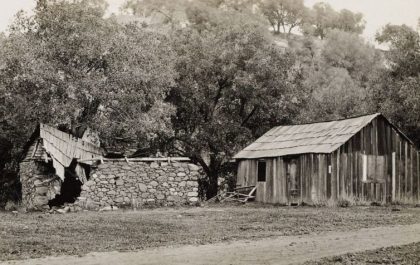

On the home front, volunteers were essential for Civil Defense, but there weren’t enough of them, especially in places like the Santa Monica Mountains. Topanga was part of the 300-square-mile, sparsely populated “Malibu District.” The government struggled to find men to serve as Civil Defense air raid and fire wardens, ambulance drivers, and other emergency personnel, reluctantly making the choice to accept women volunteers and older men in roles that would have been exclusively reserved for young men.

Women were also taking manufacturing jobs and other war work. Many Topanga residents found employment at the Douglas Aircraft Co. in Santa Monica, where they worked to build war planes like the C-47 Skytrain, and the A-20 Havoc. They were looking forward to having a paid holiday on Christmas Day—the only holiday recognized with time off and extra pay that year—all other holidays were canceled for the war effort.

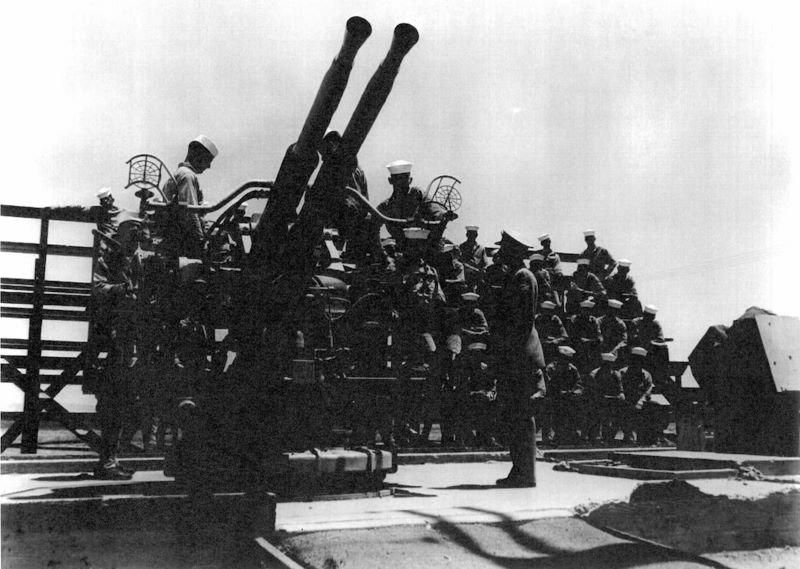

The Army arrived in the Malibu District shortly after war was declared in December 1941, and set up anti-aircraft installations overlooking the Santa Monica Bay at various locations, including Point Dume, Corral Canyon, Malibu Creek, and Pacific Palisades. The Coast Guard moved in during the summer of 1942, taking over the job of monitoring the coast from Civil Defense volunteers.

The Coast Guard was headquartered at the Adamson House in Malibu, next to the Malibu Lagoon. The officers commandeered the pool house—the government wanted the main house, but Rhoda Rindge Adamson and her husband Merritt Adamson declined, stating that they planned to remain at the house for the duration of the war. Many Malibu beach houses were empty—fears of invasion frightened many away.

The enlisted Coast Guard men camped in “hutlets”—glorified chicken coops—located between the house and the coast road. They were lucky. The house and its tall trees screened them from the wind and the constant wind-blown sand. Other local encampments, like the one up by Point Mugu, were right on the beach and offered little shelter.

The Coast Guard established two-man patrols of the entire coast. The men were eventually equipped with phones that could be plugged into jacks located on telephone poles at intervals, but in the early months they were entirely on their own, with only a dog for back up. The dogs were supposed to be military trained German shepherds, but there weren’t enough to go around, so the military drafted pet dogs. Many of them were used to a comfortable life of table scraps and sofas, and were not much use as a protection against invading enemies, but they were at least company for what was one of the loneliest assignments of the war on the home front. Local residents used to slip down to the beach to bring the men coffee and treats like cookies and donuts, at least, they did before coffee and sugar was rationed.

Rationing made even those few who might otherwise be untouched by the war feel its impact. Sugar was the first commodity to be rationed and the last to be restored. The local ration board was located at the courthouse in Malibu.

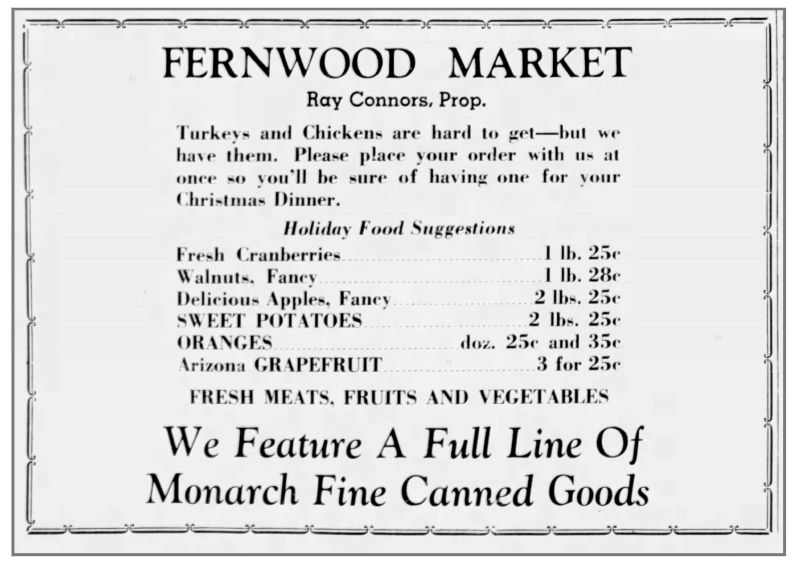

By Christmas of 1942, sugar, coffee, gasoline, and tires and other rubber products were all on the ration list, and many things that weren’t yet rationed were becoming hard to get, including parts for vehicles and appliances; and articles of clothing like shoes and women’s stockings. Turkeys, hams, and even pumpkins for pie, along with many other traditional holiday foods were requisitioned for the war effort to ensure that American soldiers would receive a lavish Christmas dinner that year—but back at home, the shelves were beginning to be bare. Fruits and vegetables were never rationed but they became increasingly scarce. Canned goods—even dog food—would soon join the list of rationed items. As the war dragged on, essentials like paper and soap started to disappear—oil and fats were diverted for the war effort, so was paper.

The Topanga Journal/Malibu Monitor, published by Hugh Harlan, was one of the small local publications that came into existence in 1942 as part of the wartime push to get information to the public. The paper is full of news about wartime fundraising activities, young men headed for military service, information on Red Cross classes, volunteer opportunities, and a hundred new laws and regulations related to the war effort, from the “dim out” rules that applied to all roads and buildings visible from the coast, to ration coupons.

Right before Thanksgiving, 1942, The Journal reported that no coffee would be available to purchase during the week of November 22-29, and that once it was made available again ration coupons would be required to obtain it. The limit was one pound per family member over the age of 15.

“The Journal believes Canyon housewives are resourceful enough to get the most from the least,” the paper stated, but a request for recipes for ways to do that went unanswered.

Sugar Stamp No. 10 was released on December 16, good for the purchase of three pounds of sugar per household—all that was available until January 31. Christmas cookies and other traditional holiday baking would be on hold for many for the duration of the war.

Every issue of the Topanga Journal featured a list of the local enlisted men. The December 4 issue reported the first Topanga member of the WACs—Mrs Jean Alexander was sworn into the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps in the last week of November. She would have a long wait before she could serve overseas. The Army had not yet figured out how to deploy the WACs. Many of the volunteers were frustrated to find themselves stuck in secretarial jobs in the states, instead of being sent to serve in the field.

Other news items from Christmas that year include a report on how the Women’s Auxiliary raised nearly $300 at a fundraiser held in Sylvia Park, and how Topanga school children raised $121.70 to buy War Stamps.

Many of those children would have been looking forward to Judge John Webster’s annual Christmas party for local children at the Malibu Courthouse. Each child received a gift, ice cream (donated by the Adamson Family’s Adohr Farms) was served, games were played, and everyone sang carols.

Public displays of holiday lights and Christmas tree lighting ceremonies were out that year. Santa Monica’s Ocean Park nativity display was dark that year. So was Altadena’s famous “mile of Christmas trees.” Hollywood Blvd’s metal holiday decorations were melted down for the war effort. On the coast, dim-out rules mandated absolute darkness at night—not even car lights were permitted. Fresh cut Christmas trees were still available, but that availability would diminish during the war years, because the manpower needed to farm, harvest, and transport the trees was diverted to the war effort.

In 1942, many Topanga residents were still homesteaders or the children of homesteaders. They were tough and resilient, used to growing at least some of their own food and doing without luxuries—but no one was prepared for air raid drills—the sirens were mounted on poles, rooftops and sometimes even on cars. The Fernwood neighborhood’s air raid siren was a homebuilt creation. The Topanga Protection Committee paid ten dollars for a siren. Zone Air-Raid Warden Jackie Robertson contributed the electric motor, and installed the siren in his own backyard. The sound “was heard in every section of Fernwood.”

Rationing; shortages of almost everything, including manpower; the absence of all of the men sent to fight in the war; and the constant fear that an invasion was imminent impacted everyone. Topanga residents, whether they agreed with the president’s policies or not, rose to the challenge that year. Their sons enlisted to fight. They raised money for the troops, collected metal and paper scrap for the war effort, and fought a major wildfire with grit and determination and not much else. Christmas 1942 was a welcome reprieve from the perpetual anxiety. Despite the shortages and fear—or maybe because of them—business boomed that holiday season, as shoppers embraced a wartime spirit of carpe diem. No one wanted to think about the war. The holiday represented the stability of tradition at a time when the world was falling apart—a welcome opportunity for festivity.

Families would have gathered around the radio on Christmas Eve to listen to the President’s message. They would know that he, too, was directly affected by the war. The Roosevelts went in big for large, festive, family Christmases. Even Fala, the presidential dog, had his own stocking full of goodies, but in 1942, the four Roosevelt sons were serving in the military, just like everyone else’s relations. The President’s message that year was austere and deeply religious. The bloodiest, most challenging months of the war still lay ahead. Roosevelt would have known that but his goal was to inspire hope and stiffen the nation’s resolve. He said:

This year I am speaking on Christmas Eve not to this gathering at the White House only but to all of the citizens of our Nation, to the men and women serving in our American Armed Forces and also to those who wear the uniforms of the other United Nations. I give you a message of cheer. I cannot say “Merry Christmas”—for I think constantly of those thousands of soldiers and sailors who are in actual combat throughout the world—but I can express to you my thought that this is a happier Christmas than last year in the sense that the forces of darkness stand against us with less confidence in the success of their evil ways.

Roosevelt might have sounded confident, but he had no way of knowing which way the war would go, and things were dire. WWII remains the costliest, most devastating military conflict in world history. America would lose nearly half a million military personnel. By the time it was over, an estimated 70-85 million people would be dead—approximately three percent of the total global population, but Roosevelt ended his 1942 Christmas Eve address with the wish that the Christmas message of peace and goodwill would “live and grow throughout the years.” Words of hope in a dark time.