Jessie and I printed the The Malibu Coastwatcher the day after Kitty and her family were forced to leave for the internment camp. It wasn’t the same without our friend and our hearts weren’t in it. I carefully used the last woodcut she had made to print her illustration on the front page of each copy. Jessie wrote an announcement that said that the publication was being temporarily suspended, and that the editorial staff was grateful for the contributions of Miss Kitty Nakamura, and that the whole community missed her and her family and wished her well.

“I don’t know if they do or not, but it’s our paper, and I’m putting it in,” Jessie told me.

I saved the copy with the best and clearest woodcut print on it to mail to Kitty as soon as she was able to send us her address.

That issue of our newsletter marked the end of the entire enterprise. Temporary became permanent. Neither Jessie nor I felt like continuing without Kitty. She finally wrote to us in mid May. She and her family were at a place called Manzanar, in the middle of the desert in the Eastern Sierras.

“I am very sorry I could not write sooner,” Kitty wrote. “We were vaccinated for smallpox and typhoid when we arrived, and my arm is still too painful to write much, but it is getting better. We have all been busy getting settled, although we have just one room and not much to put in it other than ourselves. I’m writing this on the floor. We have no furniture yet except for beds with mattresses that are stuffed with hay. My family has found jobs here, but there is not much for me to do because there isn’t any school yet. It is cold at night and burning hot during the day. The wind blows all the time, and the country around us is empty and lonely, but the mountains are very beautiful. I miss you and do not know when we will ever be home again. The strawberries must be ripe already and we are not there to pick them. Please give my love to Yuki. I am lonesome without him and I miss you all so much. Your friend, Kitty.”

Thanks to Mr Samov and a group of neighbors, the Nakamura family’s strawberry crop was harvested, but weeds and neglect soon began to take their toll on the once-neat rows of berries and bright flowers, despite their efforts. It made me sad to see it.

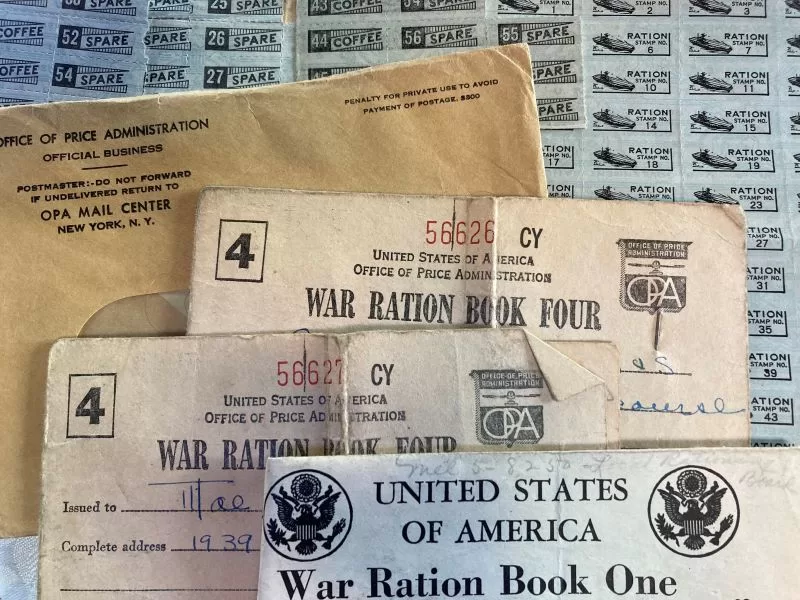

With Aunt Maddie’s help, Jessie and I put together a care package for Kitty to let her know we were all thinking of her. I put in a deck of playing cards, pencils and drawing paper, and one of my most cherished books—Robinson Crusoe, because the place Kitty described sounded a lot like being on a desert island. Jessie contributed brightly colored hair ribbons and a little hand mirror with an enameled picture of a mermaid on the back of it. She herself scorned things like that but she knew her friend loved pretty things. She also sent a big bag of lemon drops. That was a generous gift, because Jessie loved candy, and the government had started rationing sugar that month.

Aunt Maddie added cotton handkerchiefs, a bar of soap that smelled like flowers, and a pocket-sized watercolor set. The black-enameled metal paintbox was no bigger than a packet of peppermints, but it held eight cubes of paint and a tiny brush that folded up like a telescope.

“Watercolors—good ones—are hard to get because of the war,” my aunt told me. “These are from England. I bought this as a gift for your mother, who loved to paint and draw. I never had a chance to send it, but I didn’t have the heart to give it away until now.”

“Kitty will love it,” I said, feeling enormously fond of my aunt.

We also put in stationary and stamps—that was Aunt Mddie’s idea, too. “In case she can’t get them at the camp,” she said.

I added the copy of the Coastwatchers that I had saved for Kitty, a photo I’d taken of Yuki and me, a note saying how much we missed her, and three packets of garden seeds—marigolds, tomatoes, and radishes.

“I know she must miss her garden,” I said.

“Seeds are a good idea,” Aunt Maddie told me. “They are a symbol of hope, you know, and these types of seeds should be able to grow even in the desert.”

By the beginning of June, Malibu was even more of a ghost town than it was when I arrived in January. Gas and tire rationing had already made travel difficult, and new cars or even replacement parts were impossible to get. New “dim out” restrictions made driving hard for the people who had cars and gas. Dim out meant all windows and doors along the coast had to be light-proof so no light was visible outside at night, and no one could use their headlights after dark, which made it incredibly dangerous to drive on Pacific Coast Highway. You couldn’t even use a flashlight after dark.

There were stories of terrible accidents in town. The Malibu Bugle, the new newspaper in town, had a story about how two cars driven without lights, on the coast route, were smashed up in a head-on collision. The drivers were lucky. They weren’t badly hurt, but they were given citations for “Driving Through a Blackout,” and fined $25 each.

Aunt Maddie was able to get extra gas rations because of the training film project she was working on for the Navy, but getting home before nightfall on the days when she had to go to meetings was a challenge, and more than once she had to stay over in town. Mr and Mrs Calzada and Mr Zelle were there on the ranch, and I had Yuki and Mouse the cat for company, but those nights felt long and lonely.

Every day I hoped the mail would bring a letter from Kitty. I did receive a postcard from my father from Hawaii. It had a picture on it of a wide, sandy beach with coconut palms and blue, blue water on it, but it didn’t say much, except that he was OK. I kept it next to my bed, where l could see it when I went to bed and woke up in the morning. When a letter finally came it was from my sister Ally. Ally is really named Alice, and she was going to school to become a librarian. I missed her, even more than I missed our Father sometimes. She’s older than me, and ever since our mother died she has always been the one who explained things to me, and patched me up when I got hurt, and talked to me like I was a person instead of just a kid. She hadn’t written much since I came to California and she went back to her college, but she had sent cards for Valentine’s Day and Easter. This was a big fat letter. I was so excited I tore the envelope open right there at the post box.

Ally was coming to California! For a moment my heart leaped—maybe she would come and stay with us for the summer, and we could be together again. She was coming! But she wouldn’t be able to stay long, she wrote, because she had signed up to join the Women’s Army Corps and would be going to serve in the Pacific, just like Father, but she hoped to come see us before shipping out.

“Watch out for an explosion from Aunt Charlotte!” she warned.

Aunt Charlotte was Father’s aunt, which made her a great aunt, really. She wrote even less often than Father did and I no longer feared her constant disapproval. Ally was by far Aunt Charlotte’s favorite, and her anger over her must have been really volcanic because she called Aunt Maddie to complain. Aunt Charlotte hated to waste money on phone calls, and this was a long distance call. I’m pretty sure she hated Aunt Maddie, too—she was my mother’s sister—but that didn’t stop her from calling.

Malibu was still remote in those days and most people had what were called a “party line.” That meant that anyone on the line could listen in to anyone else’s conversation. Aunt Maddie had a private line. She taught me how to answer the phone when I first arrived: “Malibu 23410, Ellis Residence.” I liked to imagine I was a butler when I said it.

Aunt Charlotte’s voice sounded curiously flat on the phone. Hearing it gave me a shock. I was glad to hand the receiver over to Aunt Maddie. I could still hear Aunt Charlotte’s voice, buzzing like an angry wasp. Aunt Maddie held the phone several inches away from her own ear and waited until the buzzing stopped.

“She’s a grown woman, Charlotte.” Aunt Maddie said. “I understand that you are concerned, but Alice has every right to sign up for the WACs if that is what she wants to do. She’s an intelligent, sensible young woman, and she knows her own mind. You should be proud of her. You have raised her to think for herself.”

I don’t think Aunt Maddie liked it any better than Aunt Charlotte did, but she didn’t let it show. We were there to meet Ally’s train. I felt shy at first. She looked so grown up in her uniform, and she was wearing bright red lipstick and high-heeled shoes, but then she was hugging me and it was still Ally. I was shocked to see that even with the shoes she wasn’t as tall as she had been last time I saw her.

“You’re almost as tall as I am, James,” she said. “When did that happen? California must agree with you.”

We had four glorious days together. I showed her all of my favorite things at the ranch and took her to the beach and on all of my favorite trails. She and Aunt Maddie spent a lot of time together when I was at school. I don’t know what they talked about but I bet it wasn’t anything like what Aunt Charlotte would have said. Before she left, Aunt Maddie encouraged Ally to call Aunt Charlotte. They had a short, stiff conversation, but I think it ended with good wishes.

“There’s a last time for everything,” Aunt Maddie said. “Always try to part on good terms with people if you can, because you never know if that will be the last time you ever talk to them.”

My sister and I had one last wonderful afternoon together in Santa Monica. I took her to ride the carousel, and we ate ice cream on the pier while the gulls wheeled overhead. Then she was gone. A quick hug that smelled of apple blossom perfume, and she was off on an adventure that would take her half the world away from me. I waved until the train was out of sight. I hoped it wouldn’t be the last time.