“‘Just now our blood dances to other music.’ They fell a-twittering among themselves once more, and this time their intoxicating babble was of violet seas, tawny sands, and lizard-haunted walls.” The swallows in Kenneth Grahame’s Wind in the Willows voice the feeling that many have as late summer turns to autumn. There’s a restlessness in the air in late August. Perhaps it’s a vestigial remnant of migratory instinct, but, like Graeme’s swallows, I find myself dreaming of the desert. In the spring and autumn it’s easy to head east for a day or a weekend in the desert. In summer, the forbidding heat makes it more tempting to read about than to experience in person.

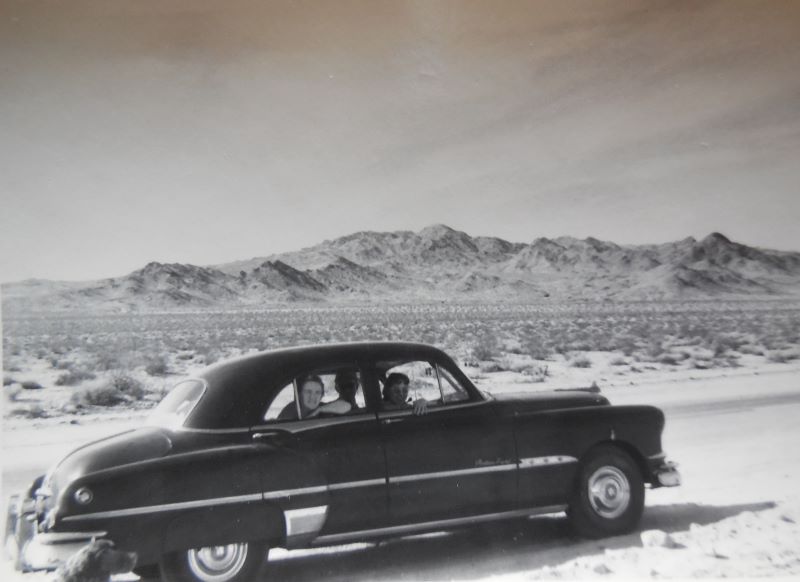

We had a whole shelf of books on the desert and the American West when I was growing up. My parents fell in love with the desert on their way to California from New York in 1953. Before my brothers and I were born, our parents spent almost all of their spare time exploring the desert. I grew up reading their books and learned to love the desert, too. I still have many of those books, and the shelf has expanded over the years to hold many more.

The books on this list are much-loved favorites, chosen for their power to evoke the landscape—and the people—of the desert, deserts as far apart as Mojave and Moab. The common thread? They are by and about people who have lived in the desert, understand it, and love it for its beauty and remarkable diversity. They share that love with readers between the pages of their books and across the years.

Edward Abbey, Desert Solitaire: A Season in the Wilderness, 1968. The opening words of Edward Abbey’s Desert Solitaire don’t exactly encourage the reader to head for the wide open spaces: “Do not jump into your automobile next June and rush to the canyon country hoping to see some of what I have attempted to evoke in these pages,” Abbey cautions. “In the first place you can’t see anything from a car; you’ve got to get out of the goddamned contraption and walk, better yet crawl, on hands and knees through the thornbush and cactus. Where the traces of blood begin to mark your trail you’ll see something, maybe. Probably not.”

Despite the curmudgeonly opening salvo, Abbey generously shares his experiences during a season as a park ranger at Arches National Monument (now Arches National Park) in vivid, concise and sometimes visceral language that brings the time and place to life—plants, animals, weather, geology, geograph, and human impacts. Abbey has harsh criticism for the park service, the government road builders, and the hordes of tourists who descend each year on the Utah wilderness, but he also captures the silence and immensity of the landscape and the intricacies of life there, down to the relationship between the mice in his ramshackle trailer to the rattlesnake under the doorstep. Fifty-five years after it was first published, Desert Solitaire remains full of indelible images: once read, never forgotten.

Mary Hunter Austin, Land of Little Rain, 1903. Mary Hunter Austin wrote Land of Little Rain more than sixty years before Edward Abbey’s Desert Solitaire. Austin lived for many years in Independence, above the Owens Valley, but the part of the country she describes in her book, what she calls the “Country of Lost Borders”—the vast area between the High Sierras and Death Valley, encompassing miles of the Mojave Desert, the rugged, dry, canyonlands of the Alabama Hills, the high mountain country.

In Land of Little Rain, Austin describes the beauty of the land, and the joys and hardships of the people and animals who made their home there. Her descriptions, like Abbey’s are vivid, and she does not sugar coat any aspect of them.

“Here you have no rain when all the earth cries for it, or quick downpours called cloud-bursts for violence,” she writes. “A land of lost rivers, with little in it to love; yet a land that once visited must be come back to inevitably. If it were not so there would be little told of it.”

Austin discovered her love of the desert and mountain country after she and her husband moved them to the Owens Valley in the 1890s. She learned to love this bleak, vast landscape, and to know it intimately, but the Land of Little Rain was just one chapter in a long, highly successful life as an author and early activist for conservation and Native American affairs.

This series of interconnected essays invites the reader into the world the author describes. “…If ever you come beyond the borders as far as the town that lies in a hill dimple at the foot of Kearsarge, never leave it until you have knocked at the door of the brown house under the willow-tree at the end of the village street, and there you shall have such news of the land, of its trails and what is astir in them, as one lover of it can give to another . . .”

Austin was a force of nature herself. She was an early feminist, an outspoken advocate for Native American rights, and a passionate advocate for conservation. She spent nearly two decades researching the Native American people of the Mojave. She was a friend of John Muir, and became an important voice in the circle of poets, writers, and visionaries who came together in Carmel in the first decade of the twentieth century. She spent the last twenty years of her life in New Mexico, where she was active in preserving local cultural heritage. She was also a prolific author of novels, plays, and nonfiction. Not everything she wrote remains relevant, but Land of Little Rain is timeless and beautiful, an enduring source of inspiration.

Peggy Pond Church, The House at Otowi Bridge: The Story of Edith Warner and Los Alamos, 1960. This is the story of Edith Warner, who at 30, traveled alone from Pennsylvania to New Mexico in 1922, and made a home for herself for more than 20 years on the edge of the San Ildefonso Pueblo, near Los Alamos, New Mexico. She quickly learned to love life in this harsh but beautiful country—”I know that no wooded, verdant country could make me feel as this one does,” she wrote. “I think I could not bear again great masses of growing things, …it would stifle me as buildings do.” Warner became a friend and confidant not only of the people of the pueblo, but also of the atomic scientists who took over Los Alamos during WWII.

Church, a respected New Mexico poet and author, used Warner’s journals to tell her story, but the language is her own, and it is poetic and powerful. The author and her subject were remarkable women who shared a love for the land and the people who lived there, and this is a beautiful—and astonishing—story. Pond intertwines the story of Edith Warner, who she knew well and loved, with the story of her own life. It’s a fascinating counterpoint to the highly acclaimed film Oppenheimer, but it has also stood on its own merits for nearly seventy years.

Church writes with love for the land and respect and affection for the unusual pioneering woman who came to the West and made a place for herself not only at a metaphorical crossroads but at a real one where a traditional past collided with the iconoclastic, atom-splitting future.

Zenna Henderson, Pilgrimage: The Book of the People, 1961. My copy of Zenna Henderson’s book Pilgrimage is battered, yellowed, and crumbling around the edges. It’s another of my father’s books. This volume of science fiction stories written more than 60 years ago may seem odd company for a book list that includes Edward Abbey and Mary Hunter Austin, but the pages of this old paperback contain vivid and evocative images of the American West written by an author who was born in Arizona’s canyon country, spent a lifetime teaching in small schools in mining and ranching towns, and who knew and loved the land and the people who struggle to make a life there.

In a way, this book shares some threads with The House at Otawi Bridge. It is also about the intersection of the past and the future, and how the two coexist—or don’t—in this raw and wild landscape. Pilgrimage is a collection of short stories published in a variety of magazines over the preceding decade. They are loosely tied together with a framework story of a troubled young woman who comes to the desert to end her life and is given new purpose through an encounter with some unusual inhabitants of Canyon Country. The stories themselves revolve around the People, refugees from another world who sought refuge on Earth in the 1890s.

Henderson was raised in a Mormon community in Arizona. She left her religion, but there are echoes of it here in the hostility the fictional People faced, including persecution, and in the sense of inclusive community they built in their new world. She witnessed another kind of alienation and xenophobia during WWII, when she taught school at an internment camp for Japanese American families forcibly relocated from the West Coast.

Most of Henderson’s stories are about children, many are about teachers. Some are filled with optimism for a better future, others are not, and even now, rereading them decades later, have the power to make the reader cry. Not all of her stories have aged as well as others, but they remain compelling. Henderson’s descriptions are vivid and her characters so convincingly drawn that she was reportedly pestered by readers convinced that the locations and the people in the stories had to be real. The desert landscape is part of almost every story, as vividly drawn as any of the characters. This is a book with a sense of place, wherever that place is.

“Then came one of the casual miracles of mountain county. The clouds suddenly opened and the late sun broke through. Almost frighteningly, a huge mountain pushed out of the featureless gray distance. In the flooding light the towering slopes seemed to move, stepping closer to us as we watched. The rain still fell, but now in glittering silver-beaded curtains; and one vivid end of a rainbow splashed color recklessly over trees and rocks and one corner of the sky.”

That’s a passage written by someone with the power not only to observe but to describe. Pilgrimage is long out of print, but in 1995, a volume with all of Henderson’s “People” stories was published by NESFA Press, under the title: Ingathering. I was not familiar with many of the later stories and found many of them more bleak than the ones published in the original volume, but still thought provoking. A second volume, published in 2020, collects Henderson’s other stories that do not revolve around the People. These two volumes, available via Kindle, hold the complete published writings of this compelling but mostly forgotten writer.

Tony Hillerman, The Blessing Way, 1970. Hillerman’s literary career had a very different trajectory from that of Zenna Henderson. The Blessing Way, published in 1970, introduced readers to Navajo Tribal Police Lieutenant Joe Leaphorn, and would go on to anchor a series of 18 best-selling mysteries. Hillerman died in 2008. His daughter Anne has continued to write new books featuring her father’s characters.

At first glance, Hillerman is an even less likely addition to this list than Henderson, but his love for the Four Corners region of the American Southwest, and his sympathetic and unsentimental portrayal of the inhabitants of the Navajo Nation was a revelation when the first book debuted.

The Blessing Way was the author’s first novel. It’s a little rough in places, and the mystery is less a whodunit than a piecing together of the chronology of events. Leaphorn isn’t even the main character in this first outing, but the landscape is breathtaking and the characters compelling. The desert is as much a presence in Hillerman’s book as the people who live and work in it.

The Blessing Way is fifty years old, but like the stories of Zenna Henderson, it doesn’t feel dated because it is so strongly anchored in its setting and time. Many new readers are discovering Hillerman’s books thanks to the popularity of a recent TV series Dark Winds, featuring Zahn McClarnon as the legendary lieutenant. The series offers an invitation to revisit the books, or explore them for the first time. Either way, they are worth the effort.

All but one of the books on this list date from the first half of the twentieth century. That’s significant, because the midcentury was a time of catastrophically damaging change in the deserts of America. Uncontrolled development: dams, mines, roads appeared everywhere, erasing cultural heritage, destroying and fragmenting the land. There is an elegiac quality to all of these writings. The words capture places that in many cases have changed beyond recognition, but while much has changed, much also remains: the wild, rugged, harsh beauty of the deserts and mountains of the American West endures, despite human folly.

Abbey described his book as an elegy for something that was already lost. If one looks hard enough, one can still find some of the things described by all of these authors, the “casual miracles of mountain country,” “news of the land, of its trails and what is astir in them,” sometimes even in one’s own backyard.