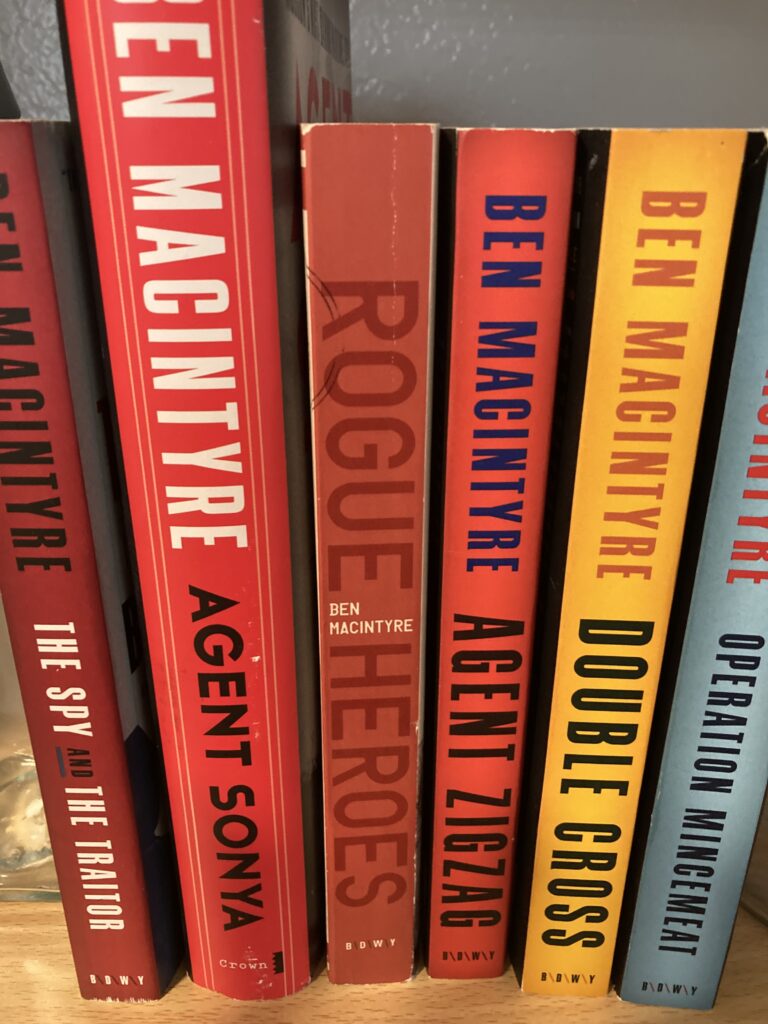

During the past two decades, acclaimed British espionage historian Ben Macintyre has helped us see the major global conflicts of the twentieth century through a different lens.

Early 1942 was a rough time for the planet. Europe and North Africa were swimming in swastikas and Japan’s “rising sun” served as a dark cloud hanging over eastern Asia and much of the Pacific. By the end of that year, Allied forces made their way into North Africa from which an invasion of continental Europe could be staged. But, where would the Allies strike?

Macintyre answers this question in Operation Mincemeat: How a Dead Body and a Bizarre Plan Fooled the Nazis and Assured an Allied Victory (2010) by taking a deep dive into recently released records of the British intelligence services to weave a story grounded in solid historical research and written with a delightfully British wit. In the process, a dead pauper and the spies who re-invented him became national heroes.

Operation Mincemeat confused the Axis Powers (Germany, Italy, and company) by floating a dead body off the coast of neutral Spain where it washed ashore and into the hands of German spies. Remarkably, the misleading “intelligence” made it to the desk of Adolph Hitler, and the deception became a critical component of the success of the Allied invasion of Sicily.

By 1943, the entire world awaited the Allied attempt to breach Hitler’s Atlantic Wall, most aggressively fortified along the coast of France. This spy story is told in Macintyre’s Double Cross: The True Story of the D-Day Spies (2012).

While D-Day (June 6, 1944) is celebrated as a critical turning point in World War II, its success was not guaranteed. The reality is that, had it not gone off as it did, Hitler would have been in a position to sue for peace and therefore kept much of Europe under Nazi control. Unimaginably, the war that essentially defines the one in which we live today might have ended, not in the defeat of Nazism, but in a stalemate.

So precarious was the D-Day invasion that its military commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, carried a note reading, “If any blame or fault attends to the attempt it is mine alone.” Fortunately for the free world, he never had to deliver the grim yet honorable message.

D-Day’s success was made possible by convincing the Germans to deploy the bulk of their forces away from the actual invasion site at Normandy. Thanks to a code-breaking program known as “Ultra” and “Most Secret Sources,” British intelligence had clear access to communications between German spy stations throughout Western Europe. This information was used to feed German officials the intricate details of a fictional invasion far removed from the beaches of Normandy.

Operation Fortitude, perhaps the greatest military deception in human history, included the creation of fictional armies made up of inflatable dummy tanks, fake aircraft, and hundreds of radio operators simulating the traffic of a massive buildup of Allied forces.

Agent Zigzag: A True Story of Nazi Espionage, Love, and Betrayal (2007) is Macintyre’s biographical account of Eddie Chapman who is described as a “charming criminal, a con man, and a philanderer.” We soon discover in Chapman that personal charm combined with a broken moral compass nurture the skills necessary to become a first-rate spy.

Trained by the Nazis in occupied France of 1942, Chapman is parachuted into England with orders to spy on the British. He immediately turns himself into British intelligence (MI5) and is set up as a double agent.

While there is no grand military invasion at the mercy of Chapman’s work, Agent Zigzag is a free-wheeling account that, as Macintyre writes, deftly explores “the thin and shifting line between fidelity and betrayal.”

In Rogue Heroes: The History of the SAS, Britain’s Secret Special Forces Unit That Sabotaged the Nazis and Changed the Nature of War (2016), Macintyre documents the formation of Britain’s Special Air Service, “the brainchild of David Stirling, a young aristocrat whose aimlessness belied a remarkable strategic mind.”

Like Eddie Chapman, this seemingly rag-tag group of unlikely heroes is fueled by the chaos of war. Operating primarily in North Africa and the Middle East, the SAS makes its way northward into the heart of the Third Reich. In April 1945, after a number of daring raids, SAS forces are the first to liberate the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, “a place that would become synonymous with Nazi barbarity.”

Macintyre’s most recently published volume spans World War II into the early days of the Cold War and reminds us that the bad guys had spies too… and sometimes those spies were gals. In Agent Sonya: Moscow’s Most Daring Wartime Spy (2020), Ursula Kuczynski is a German Jew who, in 1924 was bludgeoned by a Berlin policeman while marching in a May Day parade in support of the working classes.

As Hitler rose to power and the oppression of Jews escalated, Ursula (Agent Sonya) turned her allegiances eastward. From 1928-1950, and from the Far East to the United States and throughout Europe, Sonya remained a steadfast communist in the service of an ideal.

One of Sonya’s critical weapons was the belief that a young woman with children was unlikely to come under the suspicion of those she was spying on. As Macintyre does in all his work, Agent Sonya is exposed as a conflicted figure, trained to lie and deceive in support of the perception of a greater good.

In a Cold War thriller, Macintyre’s The Spy and the Traitor: The Greatest Espionage Story of the Cold War (2018) documents the real-life heroics of KGB officer Oleg Gordievsky who became a double agent in the service of Great Britain’s MI6.

By 1983, President Ronald Reagan’s rhetoric stirred Russian paranoia while a series of unrelated events stoked the fire that threatened to turn the Cold war hot. In a potential conflict that no side could win, Gordievsky’s calm demeanor and unique role as confidante to both sides turned down the temperature.

Ben Macintyre is the real deal; a storyteller with the panache of John Le Carre and the street credibility of an historian who has done his homework.