Topanga has been blessed with a number of amazing father figures, but this Father’s Day we are spotlighting the life of Vance Joseph Hoyt, a trailblazing conservation and wildlife advocate at a time when Topanga’s chaparral was seen as wasteland and its wildlife as vermin.

Vance Joseph Hoyt was born in 1889. He was raised by his grandfather, Edward Jonathan Hoyt, a Civil War soldier turned circus performer. Edward Hoyt, better known as Buckskin Joe, taught himself to play 16 musical instruments, learned to walk the tightrope, and had his own Wild West show that traveled to the corners of the earth. He also found time along the way to prospect for silver and gold, open a grocery store, and serve as a U.S. Marshall.

The young Vance Hoyt traveled the West with his grandfather, and learned from him “how to read and speak the language of the wild.”

Vance Hoyt left the open road and trained to be an osteopath in Los Angeles. He married his wife Ruth and had a son, Albert. He seems to have prospered but he longed for open space. In 1922, at the age of 33, Hoyt bought land in Red Rock Canyon in Topanga and built a cabin for his family.

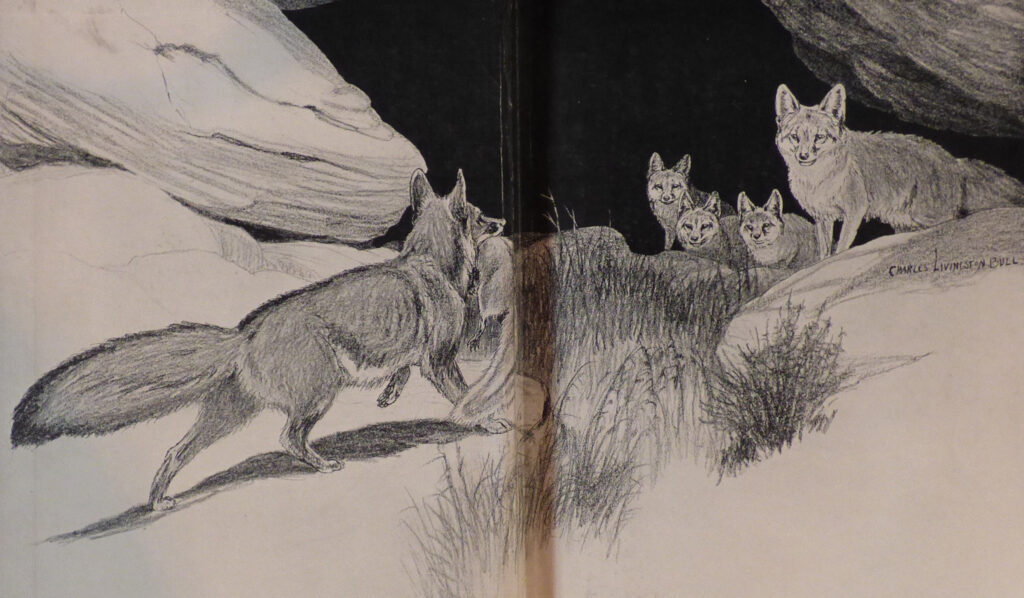

Topanga became a passion for the Hoyts. Vance, Ruth and Albert explored the mountains and filled the cabin with rescued wildlife that the family raised as pets.

Visitors to the cabin might find gray foxes or skunks asleep on the hearthrug or the cupboard full of squirrel kits.

Hoyt took meticulous notes on his family’s animals and the wildlife in the canyon that evolved into his first book, Silver Boy: Gray Fox of Topanga. The book, about a wild fox that became a member of the Hoyt family, was the start of a successful career as a writer. Books about the life of raccoons, mountain lions and deer followed Silver Boy.

Hoyt became a popular nature columnist, not just describing the natural world he observed but advocating for protections for animals and the unique chaparral ecology of the Santa Monica Mountains as well as for a more humane attitude towards wildlife.

He described the lives of wild animals and the plants of the native chaparral in detail for his readers, revealing the beauty of a hidden world with compassion and perception. Hoyt lamented that conservationists like John Muir were too focused on the mountain tops and that the wildlife and wildlands closer to urban areas were disappearing too quickly without anyone to advocate for protections.

“The trouble has always been that man has too often judged the creatures of the wild by the standards of his own behavior,” Hoyt wrote in a 1931 Los Angeles Times article on skunks, an animal that was killed by the hundreds of thousands in California for the fur trade and as vermin.

“Not only is this peaceful citizen of the animal world a square shooter, but a more cleanly, harmless and friendly beast I have never known,” Hoyt wrote, advocating for an end to the steel leg traps used on skunks and raccoons.

He was one of the first advocates for the widely reviled coyote. He argued decades ahead of his time that coyotes were critically important to control rodent populations, and described how coyotes care for their mates and young. He also documented coyotes hunting in the company of mountain lions and badgers, and made the case that “song dogs” communicate with each other across long distances when they howl, that the singing wasn’t just noise.

“Don Coyote, Canis latran—considered to be one of the most lowly and despised of all beasts is the animal that has successfully outwitted man,” he wrote in an article on coyotes in the L.A. Times in 1934. “And he has done this with a grin on his lips and taunting humor in his yaps.”

Hoyt opposed hunting in the Santa Monica Mountains in a time when hunting reports were front page material in the local papers and the mountains were a seasonal destination for every would-be hunter in L.A.

“I was appalled by the lack of knowledge of the average Californian regarding the chaparral and the animal-life we have here at the doorstep of Los Angeles,” Hoyt wrote.

In 1934, Hoyt lamented the declining amount of wildlife in Topanga. “Only at twilight and dawn can you see any more the coming and going, the stalk and frolic of the few remaining wild denizens of wood and field,” he wrote. “Those few are the ghosts of what was once recognized as the greatest resource of California.”

Hoyt continued to advocate for conservation and coexistence until his death in 1967. Although a bond was approved to purchase nearby Trippet Ranch in 1964, Hoyt died before Topanga State Park became a reality in 1974. The Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area was established in 1978, and the heart of Red Rock Canyon was acquired by the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy in 1986, ensuring lasting protections for the descendants of Hoyt’s beloved wild neighbors.

Hoyt’s son Albert shared his father’s love of Topanga and its wildlife. He worked to create the Resource Conservation District of the Santa Monica Mountains, where he was elected as a founding director; and he was a passionate environmental activist who helped to defeat development projects like the notorious Topanga Summit. He also served as Topanga’s postmaster for decades.

So this Father’s Day, why not raise a toast to the Hoyts? A father and son who were local heroes, passionate advocates for the things they loved, and who deserve to be remembered.

A great way to celebrate the life of Vance Hoyt is to take a family walk in Red Rock Canyon Park.

To reach the park, take Old Topanga Road to Red Rock Road, drive slowly and carefully through the neighborhood and continue on the unpaved road to the trailhead. Parking is $5. Facilities include restrooms and picnic tables. Dogs on leash are welcome on the trail.