Before they could vote or have equal protection under law, before there were roads or electricity or running water, a handful of women staked a claim for land in the Santa Monica Mountains. Their determination made a mark not only on the mountains but on history.

The U.S. government’s Land Act of 1862 opened surveyed public lands that had previously belonged to Native Americans to any homesteader willing to file a claim and pay a small fee. Claimants had five years to show that they were living on the land, and that they had made improvements that included building a 12-by-14-foot dwelling and growing crops.

A homesteader who could show proof of these improvements at the end of five years could file for a land patent, or deed. The patent was awarded to the head of the household, but not necessarily to a man.

More than a decade ago, historian and Moorpark College Professor Patty Colman, researching homesteads in the Santa Monica Mountains for the National Park Service, discovered that eight percent, or 31 of the 407 homesteads in the Santa Monica Mountains, were claimed by women.

Prior to the land act, most settlers in the local mountains were squatters rather than stakeholders, trying to make a life on the edges of the old Spanish and Mexican land grants. Many parts of the West experienced a land rush after the Land Act was passed, but not the Santa Monica Mountains. A period of devastating drought was a contributing factor, but the remoteness and steepness of the terrain was also an issue. In an era before roads, this small range of mountains was only accessible by horse or with a mule team.

The Santa Monica Mountains were an odd island of no-man’s land between several large Spanish and Mexican land grants. There had been few permanent residents in the area since the Chumash and Tongva people had been driven off the land and assimilated into the Mission system almost a century earlier, and the first homesteaders carved lives out of true wilderness, despite the area’s proximity to the rapidly growing city of Los Angeles.

The earliest Topanga homesteaders on record were Jesus and Elena Santa Maria, who arrived in 1880. They raised 18 children in the small wooden cabin that they built in the canyon. Manuela and Francisco Trujillo were the next to file a claim, arriving in 1886. Elena Santa Maria and Manuela Trujillo both took an active role on their ranches. Manuela served as ranch manager when her husband was away, which was often because in addition to working their land, he built a business freighting goods in and out of the canyon—an arduous and lengthy journey before the roads were built.

The early homesteads were scattered and remote. The nearest neighbors for the early Topanga homesteaders were in the Calabasas area. They included Matilda Ellis, a 60-year-old widow who arrived in 1885 and staked a claim on 10 acres near Stunt Road and Mulholland, but this was an empty and lawless land.

In 1889 the Land Office in Los Angeles began to open the last “free” lands on the West Coast. In 1895, Congress passed a new act, making smaller sections of land available for $1.25 an acre. A flood of homesteaders took advantage of the new opportunity. This second wave of settlers included Lillie Svenson, an immigrant from Norway who received a land patent in Topanga in 1910, and seized the opportunity to build a life for herself.

Lillie Svenson was one of five women homesteaders in Topanga identified by Colman. She grew grapes and planted an orchard on her homestead. Svenson worked part time as a teacher in Santa Monica, making the challenging trek from town to canyon. She never married.

Many of the women who filed for a land patent in the Santa Monica Mountains were widows, like Topanga homesteader Stella McAllister—known as “Mrs Mac.” She arrived in 1905 with her husband but was widowed a few years later, leaving her to grapple with being head of household on her own. She established the Topanga Tavern on her homestead to support herself, offering home-cooked meals and rooms for travelers.

Topanga homesteader Viola Cliett was estranged from her husband and fought a lengthy legal battle to retain her homestead and the title “head of household,” after a squatter attempted to force her off her land in 1914, using the argument that Viola could not be head of her own household because her ex-husband was still alive.

After a two-year legal battle, a Superior Court ruling upheld Viola’s right to her 120-acre ranch. A 1916 Los Angeles Times article on the decision describes Viola as “a woman of grit and intelligence,” and proclaimed that the ruling had set a “remarkable and far-reaching social precedent.”

The Times article gives a tantalizing glimpse of Viola’s daily life, describing how she took in paying guests to help support her two young children, and how she cooked and cleaned for her family and guests in addition to farming her own land, caring for the ranch livestock. She “did all the work that should have devolved on the head of the household,” the article states. An illustration shows her in an old-fashioned poke bonnet and apron, raking alfalfa in her field. The depiction may be romantic artistic license on the part of the illustrator, but it was a rough life for all of the homesteaders, and single women faced the greatest challenge. Stella died just four years later. She was only 41.

The reality for most was backbreaking labor and challenges that included wildfire, drought, bandits, and cattle rustlers in addition to more mundane hazards like crop failure or illness and injury. Modern conveniences like electricity, running water, and roads didn’t arrive in many parts of the local mountains until well into the 20th century—some of the homesteaders in the western end of the range wouldn’t have the opportunity to have electricity until the 1940s.

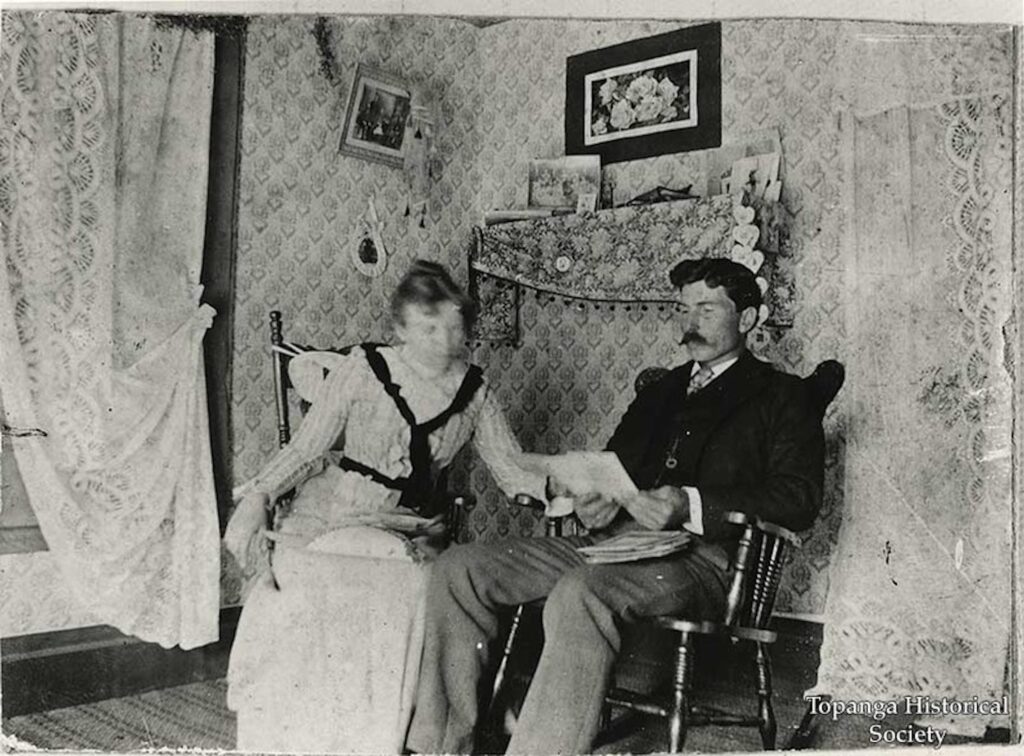

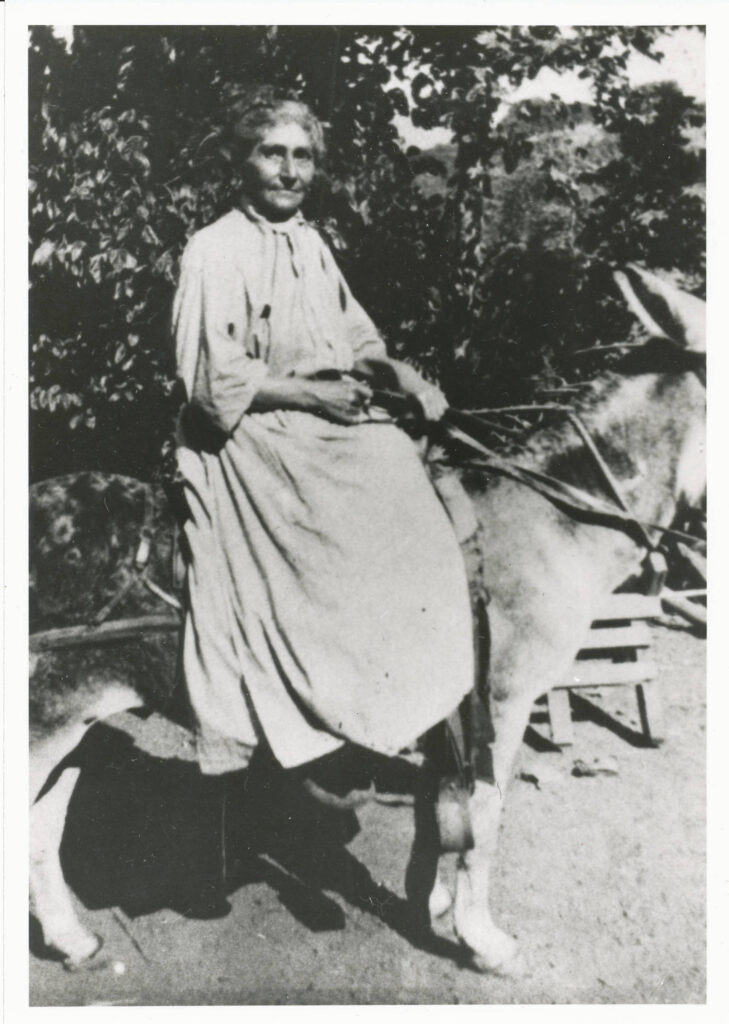

Photographs of the era reveal the hard work but also the pleasures of life in this last corner of the Western frontier. An image from around 1915 shows an elderly Manuela Trujillo, serenely and confidently riding on a burro; photos taken by Topanga school teacher Theresa Sletton in the 1910s chronicle hiking trips in the hills and picnics on the beach.

Sletton, the community’s first schoolteacher, was herself a pioneer. She lived in a tent cabin on the McAllister homestead, and spent her weekends exploring the hills and chronicling the lives of her neighbors in the close-knit, fiercely independent community.

The first generation of women homesteaders in the Santa Monica Mountains instilled their spirit of independence and determination in their descendants and successors. It still takes a certain amount of pioneering spirit to weather life here, but these remarkable women helped blaze the way.

The Topanga Historical Society’s digital archive is a treasure trove of material on Topanga’s early settlers, and the THS book is a must have for anyone interested in local history. Learn more at topangahistoricalsociety.org

Look where where my grandmother live Topanga somewhere in 1940s or 30s her name was Jeanette Daley

Wonderful history of strong women who helped pioneer settlement here in the Santa Monica Mountains. Great details. Delightful read. Thank you!

My grandmother was Clotilda Santa Maria Hurtado, one of the 18 children Elena and Jesus Santa Maria bore.

The Santa Maria Ranch was the first homestead in the Topanga area, followed soon after by the Trujillo family. My mother, Helen Hurtado Gillette was one of the six children of Chloe and Augustin Hurtado.

There is much history within the Santa Maria family, and descendants. It is a fascinating part of California history.

Two friends of mine are:

Ted Santa Maria

Robert Wiley

Thanks,

Thank you, Barbara. The Santa Maria family were true pioneers who overcame unimaginable hardships to build a life for their family in Topanga. I love that their descendants are still part of the fabric of our community!

Two of my personal friends are:

Ted Santa Maria

Robert Wiley

Thanks

Chris, remarkable people and true pioneers!