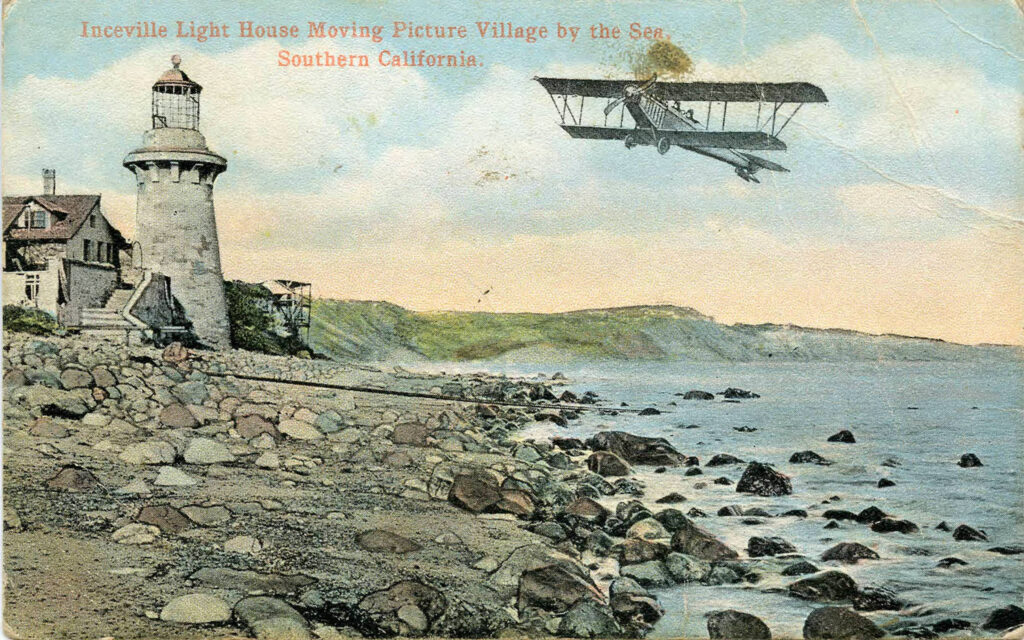

Inceville. Anyone who has ever checked a traffic app or looked for directions on the way up the coast from Santa Monica to Topanga or Malibu has seen the name on the map, but it doesn’t really exist. The only way to visit this particular corner of the Twilight Zone is in the dusty old reels of silent films from the earliest days of the movie industry.

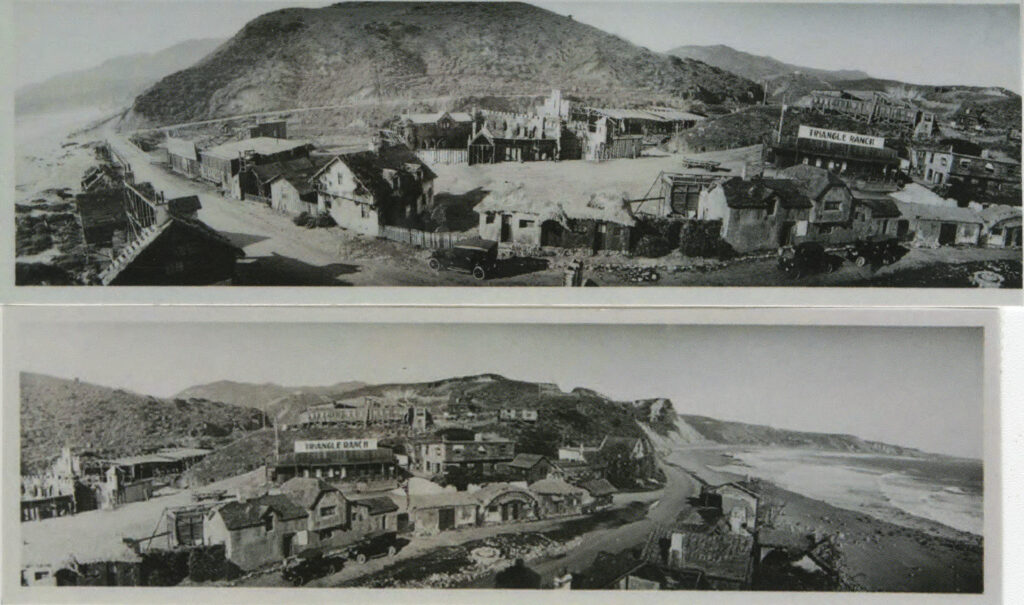

Established in 1911, Inceville was one of the first movie studios. Built by film pioneer Thomas Ince at the intersection of what is now Sunset Blvd and Pacific Coast Highway, it covered 18,000 acres at its peak, and included housing for 700. The temporary population was always shifting, but included film crews and an entire Wild West show complete with cowboys and Indians—as many as 100 Lakota Sioux, brought in from Oklahoma to work as extras in Ince’s popular westerns.

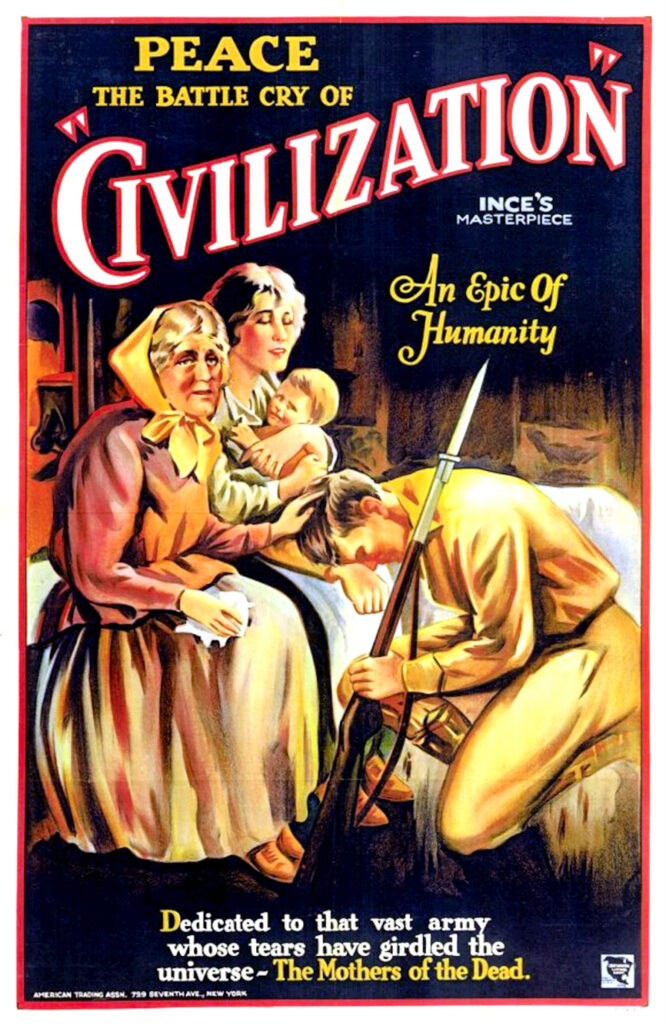

There was a Scottish village and church, a New England puritan settlement, a full-sized lighthouse, a pirate ship, and a wild west frontier Army fort, complete with log palisade. An elaborate set for the film Civilization was built near what is now Marquez Elementary School, and what is now the Self Realization Fellowship was at the heart of the old movie studio. The Santa Monica Mountains provided a backdrop for the Wild West, the American Civil War, and the European Alps. The ability to film exterior shots nearly year round gave Ince’s study a major advantage.

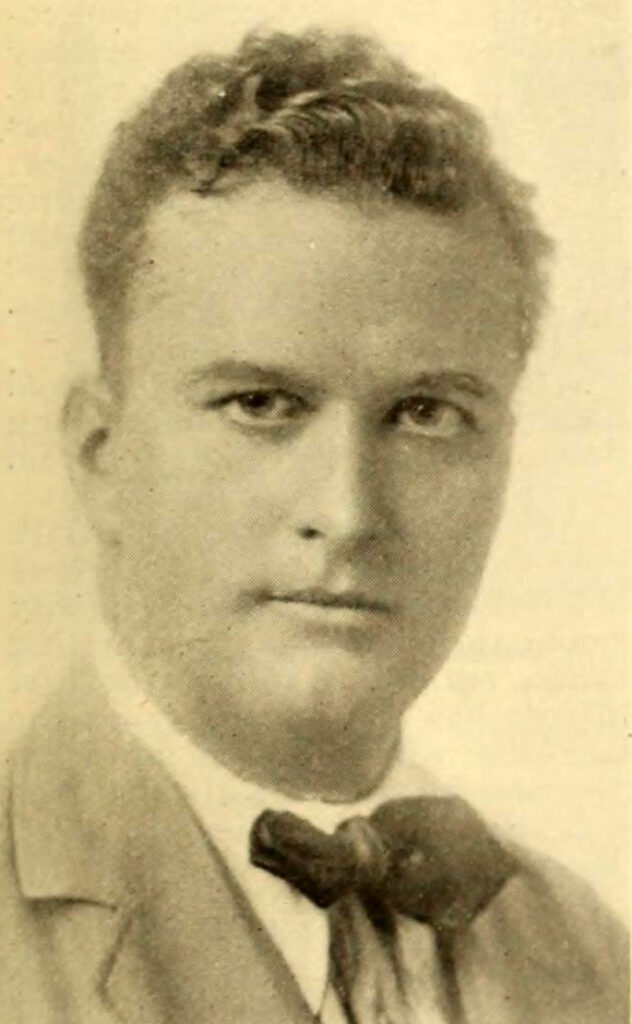

Ince had a hand in almost every aspect of the films he produced. He worked on scripts, cinematography, and often directed. He even wrote the title cards. At Inceville, he often rode his horse from one film shoot to another, sometimes directing from the saddle. His wife Elinor was often at his side. She had an active role in the business.

Ince, christened by media “the Napoleon of Inceville,” and “the King of the Westerns”, built offices for himself and his staff, camps for the extras, luxurious bungalows for his stars, a cafeteria to feed the army of employees, sheds to store film equipment and props that included carts, wagons, stage coaches, and a fleet of prairie schooners. There was also stabling for hundreds of horses, as well as corrals for oxen, bison, and other miscellaneous livestock.

In her book Pacific Palisades: Where the Mountains Meet the Sea, local historian Katherine La Hue wrote that Ince kept herds of cattle and raised feed and garden produce. “Supplies of every sort were needed to house and feed a veritable army of actors, directors and subordinates.”

Movies were a brand new industry and artform, and Ince was a pioneer, establishing many of the filmmaking techniques and conventions that we take for granted today. He was the first producer to have his own complete film studio, and the first to have multiple crews working on different projects at the same time.

There were always at least two or three films in production at Inceville, and the site seems to have been a non-stop party. Intrepid tourists made the trip in the hope of seeing Western film star William S. Hart, a longtime friend of Ince from both men’s early years in New York, and a major part of the success of Inceville from its inception. Legendary film femme fatale Louise Glaum was also a major draw. She was one of Hollywood’s first “vamps.”

Dignitaries were entertained with rodeos and picnics. Aspiring actors arrived in the mostly vain hope of being discovered, their dreams fueled by rags-to-riches stories in the newspapers of the day. Those fortunate enough to have a car traveled in style up the coast from Santa Monica. Everyone else took the red car trolleys as far as the Long Wharf at the base of Temescal Canyon and either walked the rest of the way or caught a ride in one of the studio cars. Some of the earliest reports of traffic accidents on the coast route involve visitors to Inceville.

Theater actress Billie Burke created a frontpage news sensation when she arrived at Inceville in 1915. The actress is best remembered now for her performance as Glinda the Good Witch in the 1939 film Wizard of Oz. She arrived in Los Angeles on a private railcar attended by her maid, and was wined and dined by Ince at Inceville, then swept off for a luxurious holiday on Catalina, in an effort to get her to sign with the studio. She did.

Burke’s first film with Ince, the romantic comedy drama Peggy, was a smash hit for the newly renamed Triangle Pictures Company. Burke delighted audiences. The film featured her scandalously attired in pajamas, a daring fashion choice that caused pearl clutching in the conservative media, and did a lot to popularize PJs for women everywhere. The film is one of many from the silent era that didn’t survive, but it propelled Burke to cinema stardom. She rapidly became one of the highest paid film actresses of the silent era.

Despite the successes, Inceville was plagued with problems. In 1915, a wildfire burned through Inceville, destroying many buildings. In February 1916, a fire that broke out in the cutting room next to Ince’s office, badly injured the filmmaker and eight of his employees. Early nitrate film was highly flammable, but the blaze may have been started by an arsonist. There was a fire the same night at Ince’s brand new Culver City studio.

In April of 1916, a landslide north of Santa Monica Canyon cut off access to the film studio for several weeks, further delaying filming and rebuilding work. In 1917, three crew members were killed and three more seriously injured when a mudslide caused scaffolding to collapse on the site of a William S. Hart western.

A third devastating fire occurred in October 1923. This was a Santa Ana-driven wildfire. The Los Angeles Daily News reported the incident on October 15, 1923, and stated that the fire ignited at the top of Santa Ynez Canyon and burned all the way to the sea. It “virtually wiped out Inceville, a well-known collection of motion picture sets,” the article states. “Only one building, a church front, remained after the fire had spent itself.”

Some accounts state that part or all of Inceville had already burned in July of 1922. There aren’t any news reports of a 1922 fire, but filming appears to have stopped at the famous studio in 1920, and it no longer appeared in the news. Whether there was anything left to burn in 1923 or not, Inceville was already a ghost town. The stone church, built for the film Peggy in 1915, endured for another decade as a local landmark. It was pulled down in October 1933.

Ince died in 1924. He was only 44. Rumors surrounding Ince’s death cast a lasting shadow over his legacy. The official cause was a heart attack and the facts support that finding, but allegations of murder have never been fully disspelled. That’s unfortunate, because this silent film pioneer, who made more than 800 films in just two decades, deserves to be remembered for his contributions to his craft.

In a 1919 interview in the San Francisco Call, silent film star Dorothy Dalton described Inceville as “the most romantic of all motion picture encampments.” Today, all that is left of Inceville is the name on the map, the ghost of a short-lived but larger-than-life chapter in American cinema. Many of the films shot at Inceville have not survived, but William Hart’s allegorical Western Hell’s Hinges, released in 1916, offers a glimpse of Inceville in its heyday. Ince’s big budget 1916 extravaganza, Civilization, has also survived. The subject matter of Custer’s Last Fight, released in 1912, is challenging for contemporary audiences, but it offers a fascinating look at Ince’s army of extras, including some of the Native Americans he brought to California from Oklahoma. All three films can be viewed on YouTube.