Instead of Topanga’s rugged mountains and oak-forested canyons, imagine a city with a population of 60,000, straight off the cover of a 1960s paperback sci-fi novel—sky towers clustered on mountaintops, and high rises cascading down steep cliffs—all that is missing is an extra moon or two and a rocket ship. In the 1960s, that was architect William Leonard Pereira’s vision for a vast swath of the Santa Monica Mountains in Topanga.

The postwar Los Angeles building boom covered nearly every square inch of the Los Angeles Basin in urban sprawl. By the 1960s, developers turned their attention to the Santa Monica Mountains, and who better to build a city of tomorrow on the mountain tops than William Pereira?

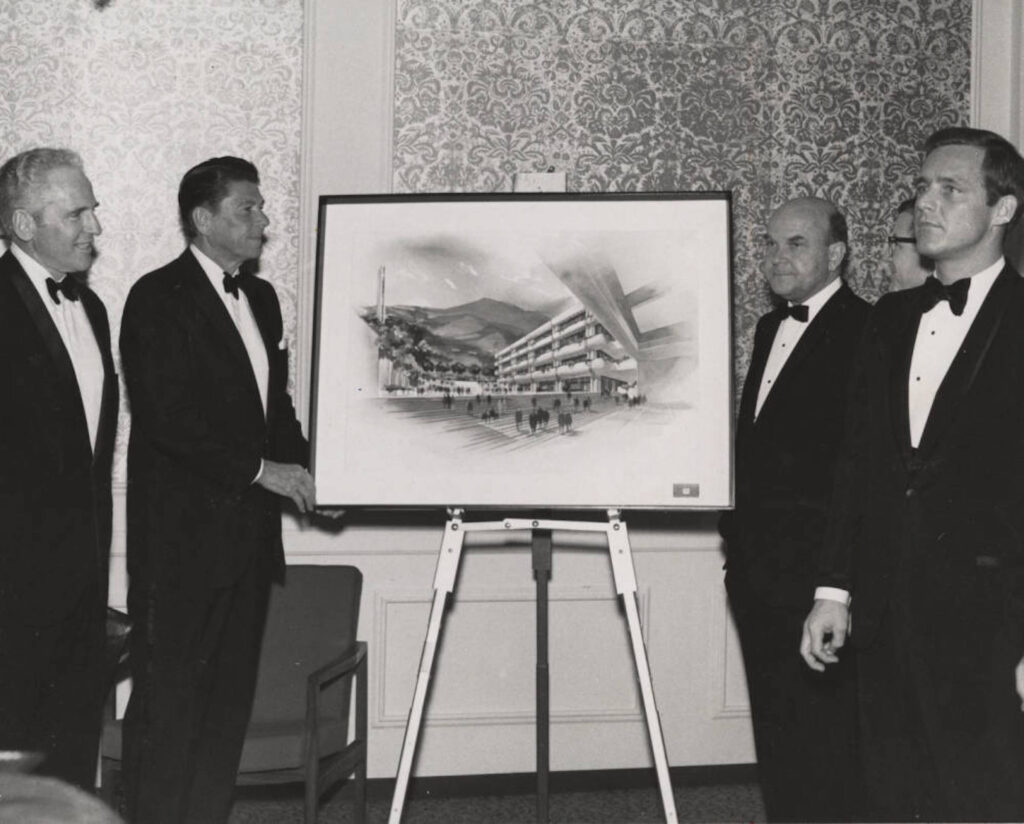

A charismatic architect with a love of science fiction and fast cars, Pereira put his personal stamp on mid-century Los Angeles with more than 300 futuristic designs. Pereira was born in Chicago in 1909. He received his degree in architecture from the University of Illinois’ School of Architecture, and moved to Los Angeles in 1933.

A talented artist as well as an architect, Pereira initially worked in the film industry as an art director. His credits include Gone With the Wind and Cecile B. DeMille’s 1946 film Reap the Wild Wind, which earned him an Academy Award. Pereira soon established himself as a professor of architecture at USC, and rapidly became one of the most sought-after architects in the country. By the time he was approached for the Topanga project in the early 1960s, Pereira had a formidable reputation. His most famous building is the Transamerica Pyramid in San Francisco, but his resume is extensive and diverse. It includes the original Los Angeles County Museum of Art; the Disneyland Hotel in Anaheim; Marine Land in Rancho Palos Verdes; the CBS Television City, in Burbank; and the Brutalist 1972 addition to the original Los Angeles Times building in Downtown L.A. He even designed parts of NASA’s Cape Canaveral facilities, and many of his buildings suggest something that just landed from outer space or is about to blast off.

When Pereira was selected to design Mountain Park—the name selected for the proposed new city in Topanga—he was in the process of developing a master plan for 93,000 acres of undeveloped land in Orange County that would become the cities of Irvine and Newport Beach.

The 10,700-acre Mountain Park project site was located between Topanga and Sullivan canyons, bounded by Mulholland Highway to the north, and Sunset to the east. The land was owned by corporate interests, headed by investment banking firm Lazard Freres & Co. The investors were eager to build out the area, but were aware that there were geological constraints and vociferous opposition from Topanga residents and other neighboring communities.

Pereira was selected to design a ridgeline city that would set this development apart from what he described as the “peanut butter spread” of urban sprawl. The plan he developed featured 10 “mountain villages,” each with housing, churches, shopping centers, schools, industrial facilities, and a park. The “villages” would be connected to by a six-lane Mulholland Highway.

In defiance of the Santa Monica Mountains geologic activity, Pereira designed what he called “cluster housing,” dense concentrations of tall apartment complexes clustered around views and central parks.

Pereira also proposed gravity-defying “cascade housing” that would take the place of high rise buildings in steep terrain. These buildings would be constructed down from the cliffs and accessed by “inclinators,” described variously as a cross between elevators and escalators or as a kind of funicular.

Pereira designed “facilities concealed in architectural caves in the steep canyons.” An August 12, 1962 Los Angeles Times article describes them as “Industrial installations at the bottom of precipitous canyons, roofed over for complete control of temperature and air content, and noise.” The architect doesn’t appear to have suggested exactly what one would do in an architectural cave, but he confidently stated that by roofing over 100 acres of box canyon, jobs could be provided for half of the 60,000 new canyon residents.

Topanga only had a population of around 3,000, but the community rallied and pushed back, hard. Topanga resident and architect Bob Bates, together with his wife Donna, and a small group of dedicated activists founded the Topanga Association for a Scenic Community (TASC) in October 1963, the year the plans for Mountain Park surfaced.

In an effort to appease the critics, the plan was modified to include 1,400 acres of open space. The critics were not impressed. They argued that the land set aside for a park was too steep to be built, and was therefore no loss for the developers. The project’s opponents continued to protest. They called for a building moratorium and enlisted experts who raised questions about geology, earthquake safety, fire risk, road access, and environmental impact.

Together with the Santa Monica Regional Park Association, TASC volunteers gathered more than 10,000 signatures opposing the plan. They advocated for preserving the mountains and creating a real park. Pereira didn’t help his case when he stated, “Our need is not for a vast park.” The plan to expand Mulholland Highway into a six-lane freeway to facilitate the build-out didn’t do much for the architect’s case, either. The engineering challenges for that highway, and the massive expense of building it helped turn the tide in favor of the conservationists. Today, the area is part of Topanga State Park.

It’s unclear if any of Pereira’s imaginative designs for geologically unstable Topanga were feasible, and it was quickly apparent that the developers were seeking maximum buildout and had no real intention of pursuing the architect’s vision. Pereira’s futurist design for Mountain Park, not unlike the work he had done for the movie industry, was an illusion used to sell a story.

Even while Pereira was working on his masterplan, the developers quietly sold off 3,250 acres of the Mountain Park property that later became the Sunset Mesa subdivision.

Pereira had his chance to make his mark on the Santa Monica Mountains a decade later, when he designed Pepperdine University’s 830-acre Malibu campus. It’s not a radical design like the one he made for Mountain Park, but the red-roofed buildings are clustered on the ridges to take advantage of the view, in the way he envisioned the towers of Topanga, and the school regularly tops lists of the most beautiful university campuses in America.

Pereira died in 1985. Despite being one of the leading architects of his era, his legacy hasn’t fared well. Many of Pereira’s buildings have met with the wrecking ball. Irvine has largely abandoned its master plan, infilling and erasing the architect’s blueprint for the future. Even the last remaining part of Pereira’s Los Angeles County Art Museum, once praised as an “art acropolis,” was recently demolished to make way for Swiss architect Peter Zumthor’s twenty-first century replacement.

Pereira had a major impact on the shape of Southern California and remains a presence in the history of the Santa Monica Mountains, for what he created here and for what he didn’t. Pereira’s belief in the future—even if it wasn’t the future Topanga wanted—remains a part of his legacy.

Thank you for your acknowgement of Bob and Donna Bate. They are my heroes. The formation of TASC in 1963 had a group of courageous and strong people. Without them Topanga would not be what Topanga is today.

Many land use battles followed: The proposed Airport on the Messa, The fight that took. us to the California Supreme Court where we won another major land use battle and of course the 18 year fight to save Summit Valley at the top of the Canyon. In each case Topangans stood strong. We continue to protect our canyon. Forever Topanga.