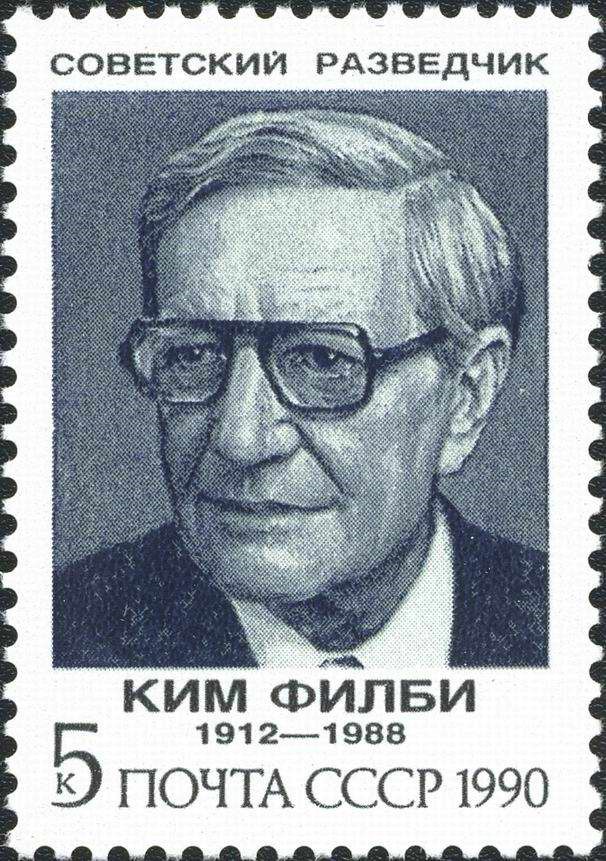

British intelligence officer Kim Philby spent nearly his entire career as a double agent (from 1934 to 1963), in the employ of the Soviet Union.

A bona-fide historical account of his enduring double life is told by journalist and historian Ben Macintyre in A Spy Among Friends: Kim Philby and the Great Betrayal (2014).

While attending Cambridge University during the Great Depression in the 1930s, Kim Philby and a number of his classmates (The Cambridge Five) were recruited by the Soviet Union’s intelligence service. As fascism took hold in Europe, these young idealists saw Soviet communism as the better political system. They also opposed the classism that demarcated British society and the imperialism that had created an empire. “His beliefs were radical but simple,” Macintyre writes, “the rich had exploited the poor for too long…”

Born into the upper ranks of British society, Philby claimed that it was his social standing that allowed him to spy so freely for the Soviets; because no true gentleman would ever do such a thing. He was also amazingly lucky, for there were many moments when it appeared that his game was up.

During World War II, Philby justified his betrayal as it was carried out in support of an ally of Britain against Nazi Germany. By the time the war ended and the Soviet Union became the sworn enemy of Britain and the West, Philby became a full-blown traitor who delivered mountains of intelligence to his Soviet handlers.

In 1949, Philby became the chief British intelligence officer in Washington, DC and he worked closely with the newly-formed Central Intelligence Agency. The CIA’s effort to arm and support those fighting against communism throughout Eastern Europe inexplicably failed time and again. Hundreds of CIA operatives were killed engaging in missions against an enemy that knew exactly how and when they were coming.

For his part, Philby later claimed that his work as a double agent prevented World War III and these deaths were a small price to pay to prevent Armageddon. Remorse is nowhere to be found.

After two of his Cambridge Five colleagues were pegged as double agents in 1951, they successfully flew the coop and made their way to Moscow. Philby was accused of tipping them off; accused of being “The Third Man.” While nothing conclusive was discovered, he was forced to resign from MI6 (Britain’s CIA equivalent). In 1955, a Member of Parliament publicly denounced Philby as a Soviet agent. The entire affair became a political lightning rod and Philby emerged, as he often did, unscathed. Incredibly, he returned to MI6 for another eight years where he reconnected with the KGB (Soviet version of the CIA).

During a filmed press conference celebrating the clearing of his name, Philby bamboozled everyone, as Macintyre writes, with “a display of cool public dishonesty… Philby looked the world in the eye with a steady gaze and lied his head off. Footage of Philby’s famous press conference is still used as a training tool by MI6, a master class in mendacity.”*

In 1963, Philby’s cover was finally blown. In true “Philbian” fashion, Macintyre suggests strongly that the double agent was allowed to escape to Moscow in order for the security service to avoid the embarrassment of a trial.

For the next twenty-five years, Philby lived in Moscow where, for many years, he was also under watch by the KGB who suspected that he might be acting as a triple agent. At one point, Philby appears to brush elbows with a young KGB officer Vladimir Putin, which reminds us that we are not as far removed from these events as we might imagine.

In 1981, Philby delivered a seminar to East German spies and a video account offers insight into this human enigma. While viewing, the enormity of his betrayal is quickly forgotten under his cheerful wit, and a lighthearted view of the world and all of its oddities. These are, of course, the disarming skills of a master spy.*

Macintyre’s history reads like a novel written by John Le Carre or Ian Fleming, two of the greatest espionage novelists of the twentieth century; a fitting comparison in a genre where truth and fiction walk hand-in-hand through the fog of deceit.

It is no coincidence that Fleming’s James Bond and Le Carre’s George Smiley were dreamed up by two former British spies.

Fleming the actual spy pops up several times in A Spy Among Friends and many of his Bond characters are modeled after those with whom he had worked. For Le Carre’s part, his career with MI6 (Britain’s CIA counterpart) came to an end, in part, as a result of Kim Philby’s subterfuge. One of Le Carre’s most famous books—also a fine movie and TV miniseries—Tinker, Taylor, Soldier, Spy, revolves around a “Kim Philby” character.

Macintyre freely admits that the Philby story, decades after-the-fact, continues to inspire controversy. Much of the official record has yet to be released which leaves this historian relying heavily upon the reports of those who have spent their lives deceiving others. As Macintyre writes, “Spies are particularly skilled at misremembering the past.”

Despite the shortcoming, Macintyre does a masterful job examining the relationships Philby developed as he led a double life. Close friends and family had no idea the hard-drinking British spy was a double agent.

Some operatives, such as Jim Angleton of the CIA and Nicholas Elliott of MI6, spent most of their careers sharing their tightly held secrets with a Soviet spy.

Kim Philby treated the entire affair as a perfectly reasonable way to live one’s life and he reflected later that the friendships he had with these men were sincere. Of course, in the end, Angleton and Elliott didn’t quite see it that way.

“On the subject of friendship,” Philby said in 1955, “I prefer to say as little as possible, because it’s very complicated.”

Complicated, indeed.

*This BBC report covers the Philby story quite well and includes the Philby press conference following his exoneration in 1955, his seminar before East German spies in 1981, and a take on the posthumous awards he received from the Soviets two years before the USSR collapsed.

https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-35943428