“The past is a foreign country,” author L.P. Hartley famously wrote in his book The Go-Between. Perhaps that’s why we hold on to the postcards and snapshots, the matchbooks and other ephemera that fill the bottom of the kitchen drawer or the box under the bed. Seeing those things opens for a moment a window on favorite places we’ll never see again, on memories of ordinary things made extraordinary through their absence. “Do you remember? Were you ever there?”

Today, those relics have taken on a new significance, not just as items that jog the memory, like Marcel Proust’s stale madeleine cake in the Remembrance of Things Past, but as an important part of the cultural record of the 20th century. Matchbooks, menus and postcards have moved from the attic to the archive, forming part of the record of our daily lives.

There’s a significant collection of menus at the Los Angeles Public Library; Loyola Marymount is home to an impressive assortment of local postcards; and there is a growing repository of matchbooks and other ephemera at Pepperdine University’s Payson Libraries.

Melissa Nykanen is the former associate university librarian for special collections and university archives at Pepperdine University. In 2018, I interviewed her about the role materials like these have in research. She described it as a way to “expand history.”

The Tudor House matchbook, although somewhat battered, is the author’s favorite for the memories it evokes of elegant afternoon teas in an atmosphere straight out of an Agatha Christie novel. The tea room and shop were for decades the heart of the British expat community on the Westside, and a favorite destination for Anglophiles. The Malibu Pier Club was a short-lived restaurant that bridged the gap between the original Malibu Sports Club restaurant on the pier, and the much-loved Alice’s. The logo on the matchbook is just about all that is left from this late 1960s eatery. The Magic Pan was a small California-based chain of restaurants that specialized in crepes. There was one at the Promenade mall in Woodland Hills and one on Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills. It was wildly exciting to watch the patented crepe-making machine turn out perfect pancakes. The last Magic Pan closed its doors in 1995. Brunch is no longer served at the serene and inviting Santa Ynez Inn in Pacific Palisades, but the building that housed this local favorite retains its mid-century charm and feeling of tranquility in its current incarnation as a Waldorf school. The Raft was the Reel Inn’s previous incarnation. Its bar, “the Zoo,” was said to be popular with the Hollywood crowd and had a wild reputation. Photo by Suzanne Guldimann

“Ephemera is increasingly important,” she told me, explaining that it can offer insight into aspects of everyday life that could be almost impossible to find in more traditional archival materials like newspapers. Menus can reveal food trends and economic data—allowing researchers to track everything from when items like fresh coffee or apple pie become popular menu items, to the availability and price of oysters over time. Postcards offer a snapshot of architecture, cars, and even clothing, and provide a record of lost landmarks. Matchbooks are a miniature snapshot of the time and place, with logos, addresses, photos and phone numbers.

Ephemera, including matchbooks and menus, is part of a nostalgic and delightful exhibit up now at the Skirball Cultural Center that celebrates the Jewish Deli, its history and legacy.

“I’ll Have What She’s Having” is a nostalgic and entertaining look at a vanishing cornerstone of food and culture.

That show, co-curated by Skirball curators Cate Thurston and Laura Mart, together with writer and producer Lara Rabinovitch, a specialist in immigrant food cultures, inspired reflections on some of the ephemera right here at home. What I found is a cross between a Twilight Zone version of the Zagat Guide and an archeological expedition that reveals the curious culinary proclivities of a vanished era and a glimpse of places that live only in memory.

Our kitchen drawer is full of memories. A matchbook from Don the Beachcomber in the 1970s is only a ghost of the original Malibu Tonga Lei restaurant and hotel’s mid-century Tiki splendor, but one from the Sandcastle Restaurant at Paradise Cove preserves a glimpse of the pier that vanished in a 1983 storm. The Magic Pan in Woodland Hills,—one of a small chain of restaurants specializing in crepes—disappeared in the 1990s, taking its recipes for cherries royale and pottage St. Germaine with it, but the beautiful and elegant Chinese Restaurant Jade West in Century City, which opened in 1973, endured for decades, closing just a few years ago.

We’ll limit today’s culinary time travel trip to a few select stops on the coast, starting with the Tudor House, 1403 2nd Street, in Santa Monica. The matchbook may not look like much, but this was the heart of the Westside’s expat British community for half a century. The tea room served scones and Cornish pasties, Eccles tarts, and cucumber sandwiches artfully arranged on tiered trays. The shop supplied tea and teapots, biscuits, Christmas crackers, and Vegemite, for homesick Brits and Anglophiles.

The shop survived a move and three successive owners, all passionately committed to tea, but it couldn’t survive the 2008 economic downturn. It closed its doors in 2012.

Our next stop is the Santa Ynez Inn, 17310 Sunset Boulevard in Pacific Palisades. This quintessentially California ranch-style motel and restaurant opened in 1947. It was designed by architect Alfred T. Gilman, and featured the popular fireside room, a banquet room dominated by a massive mid-century stone fireplace.

“Delightful Dining, Hearty Hospitality, Superb Setting,” a matchbook from the 1950s enthuses. The Santa Ynez Inn was a favorite location for romantic assignations and the Hollywood set—regulars reportedly included Cary Grant, Joan Crawford and Howard Hughes, if the gossip columnists of the time are to be believed—but it was also a gathering place for family brunches on lazy Sunday mornings—eggs Benedict, Canadian bacon and fresh-squeezed orange juice, served under the bougainvillea vines.

Plans to transform the tranquil motel into 80 high rise condominium units were foiled in 1975 by a fledgling Coastal Commission, and in 1976, the property became the American headquarters of Transcendental Meditation, instead. Today, it’s a Waldorf School, its architecture—and feeling of tranquility—remain intact.

Like The Santa Ynez Inn, the Reel Inn, up the coast at Topanga and PCH, dates to 1947. It’s original incarnation was Marino’s, one of two restaurants by that name started by a family of Greek fishermen. According to author and Topanga Historical Society archivist Pablo Capra, Harry and Anna Marino started the business in 1933, cooking and selling fish caught by the family in long boats right off the coast.

The official history of the site, provided on the Reel Inn website, is worthy of a noir novel. It features remenicences by longtime former bartender Ralph O’Hara, who remembered when the business was a Mexican restaurant (the Caracol), owned by a gay couple, who were “muscelled out—literally— by “Fat Jack McGurk”, a 400+ lb retired wrestler. After a brief stint as the aptly named “El Gordo,” McGurk renamed the restaurant “the Raft,” shortly before selling it to Jim McDonald in 1967, who would later open the Sandcastle Restaurant at Paradise Cove.

The Raft’s bar, “The Zoo”, became a favorite spot for the Hollywood bad boys of the 1960s and ‘70s, including Lee Marvin, before the restaurant evolved into its current incarnation as the Reel Inn in the late 1970s, after a fire damaged part of the building in 1978. Topanga Fish Market proprietor Warren Roberts had a hand in the Reel Inn’s old-school fish market restaurant vibe.

With its perpetually punny black board and its rustic ambience, it remains a favorite with visitors and locals—a little bit of history not yet erased by the growing tide of gentrification. However, its days could still be numbered. At least one of the Topanga Creek restoration project proposals currently under consideration calls for the removal of the historic eatery.

There’s a restaurant nearby that is also owned by State Parks, but is safe from the wrecking ball, if not from sea level rise and climate change. Iconic is an overused adjective, but one could argue that the restaurant on the Malibu Pier, with its distinctive and instantly recognizable Spanish fantasy tower has earned the description.

A California State Parks’ brochure on the Malibu Pier’s history sheds light on the eccentric building’s history:

“During World War II, the end of the pier served as a U.S. Coast Guard daylight lookout station until an intense storm in the winter of 1943-1944. The end of the pier, including the bait and tackle shop, was destroyed and had to be rebuilt. The remains of the pier were sold to William Huber’s Malibu Pier Company for $50,000 with the proviso that he would construct a building for the Coast Guard to re-occupy. After the end of the war, Huber expanded the pier and built the familiar twin buildings at the end for a bait and tackle shop plus a restaurant…The building near the land end of the pier (intended for the Coast Guard) became the Malibu Sports Club Restaurant…”

The Malibu Beach Sports Club opened in 1956 and lasted until 1968. There is a lot of material from the 1950s about the restaurant, including a puff piece in the Los Angeles Examiner in June of 1958 with photos that show mountains of meat and seafood bedizened with paper frills and cellophane-topped toothpicks, rising from seas of artfully piped mashed potatoes.

In 1968 the Malibu Beach Sports Club became the Malibu Pier Club—”Except for the sound of the surf, you could imagine being on an ocean liner!” In the 1970s, the building changed its button-down yacht club aesthetic for a more pop culture feel, becoming Alice’s Restaurant. The name came from Arlo Guthrie’s song:

You can get anything that you want at Alice’s restaurant

You can get anything that you want at Alice’s restaurant.

Walk right in, it’s around the back

‘Bout a half a mile from the railroad track.

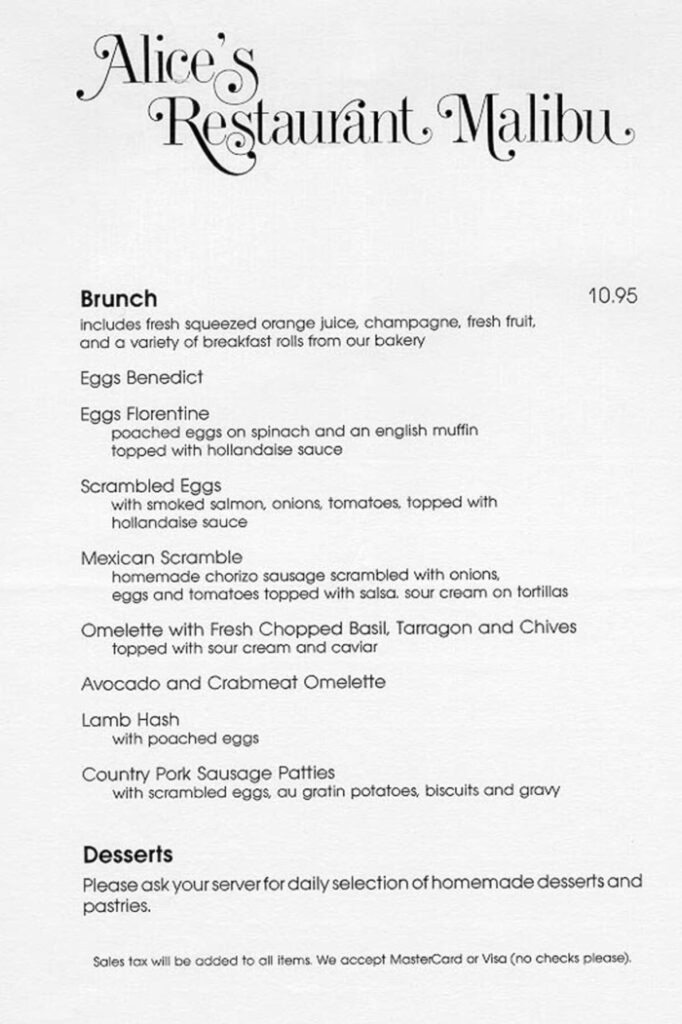

Guthrie himself doesn’t appear to have had anything to do with it, although he was a Topanga regular, and while the name suggested hippie culture, the menu was mainstream ‘70s and ‘80s cuisine, beginning with industrial strength French onion soup and ending with New York style cheesecake. Whether it was the food or the location, Alice’s was popular, and endured for nearly 25 years.

Curiously, the restaurant really was near the railroad tracks. Long after the grandly named and extremely short lived Malibu, Hueneme and Port Los Angeles Railroad vanished off the map, the train shed across the street from the pier lived on as a series of shops, including Malibu’s first bookstore and an early Malibu health food store called the Rainbow Grocery. The Lion’s Club members who meet at the Sports Club restaurant every month, to dine on lobster Thermidor and rack of lamb might be astonished to be served the raw Brussels sprout salad with quinoa and arugula that is on the menu of the Malibu Farm—the location’s current tenant—but the new menu might have been a welcome change from the Stroganoff and hollandaise sauce that dominated Alice’s menu for much of the restaurant’s tenure.

Because of its unique location at what is now a historic landmark and state park property, this space has enjoyed an unbroken tradition as a favorite restaurant—the decor and the menu may change, but the view of the pier and the water remains the same.

Restaurants come and go, but because we celebrate so many of our milestones at them they have a special nostalgia for us. They remind us of lost loved ones, and revive old joys. Perhaps that’s why we feel their loss so keenly and why we look back on them, through the rose-colored lens of memory with so much affection, and why we are reluctant to let go of that battered matchbook—because it holds memories, even when it no longer holds matches.

“It isn’t necessary to imagine the world ending in fire or ice,” Frank Zappa once quipped. “There are two other possibilities: one is paperwork, and the other is nostalgia.”

Ephemera is where those two fates come together. Eggs Benedict anyone? And, um, is there a vegan version?

For more information on “I’ll Have What She’s Having: The Jewish Deli,” at the Skirball Cultural Center, visit http://www.skirball.org/exhibitions/ill-have-what-shes-having-jewish-deli

Restaurants of all kinds depend on their patrons. Please support our current independent eateries, whether eating in or taking out.