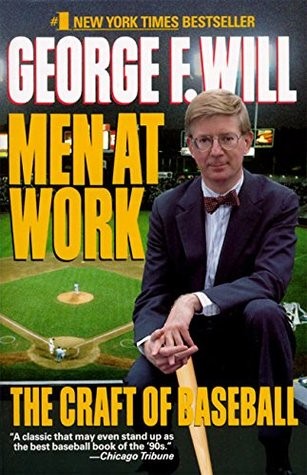

I recently revisited one of the finest baseball books of all time: George Will’s Men At Work: The Craft of Baseball (1990). I offer as evidence the book’s ability to stir in me some early baseball-esque memories.

When I turned 14 years old in May of 1974, I lived with my mother at 2371 Chickasaw Street in Cincinnati, Ohio.

She/we were at the tail end of a second failing marriage and the previous few years had been witness to a rotating cast of step-this and step-that along with the obligatory relocations that accompany such things; which is my way of saying that the privileged economic and familial situation into which I was born had deteriorated.

If you sense a bit of self-pity here, you wouldn’t be far off the mark. Chickasaw Street has become a thing for me, an albatross of sorts. I am unable to let go of the idea that I somehow deserved better…without, of course, any legitimate evidence to support the notion I had been cheated out of anything…armed only with the personal adolescent observation that “our neighborhood used to be nicer, right?”

Chickasaw Street has also become a symbol of rebirth for me, although this more positive outlook came about much later. It was where my mother, after five kids and two marriages, valiantly rebuilt her life. And she did this with hard work and a personal commitment to improving herself and her station; and all of it in steadfast defiance of the 1950s-hand she had been dealt. June Cleaver she was not.

And, here’s the baseball story in all that. Through the entire summer of 1974—and much of my life beyond that—baseball offered a comforting soundtrack, a rhythmic and reliable distraction, a daily reminder that there was a larger world out there.

From my perch on the heights of Cincinnati’s Clifton neighborhood, it was only a few miles south down to the Ohio River and Riverfront Stadium; home to the Cincinnati Reds who were in the early years of a dynasty that spanned the entire scope of the 1970s. They would go on to win back-to-back World Series championships in 1975 and 1976 but during that summer of 1974, they were already being referred to as The Big Red Machine.

As fun as these Reds were, I was already a devoted fan of the Detroit Tigers. Born in Ann Arbor, Michigan in 1960 as my dad attended the University of Michigan, I decided as an eight year-old in 1968 that the Detroit Tigers were to be my team; a conundrum for my dad, a life-long fan of the New York Yankees.

I would like to say that I chose Detroit solely due to geographic proximity to my place of birth—the typical manner in which fans become fans—but the Tigers were one of the best teams in baseball that year. Indeed, they went on to win the World Series in spectacular fashion; dousing any chance that at nine or ten I might be tempted to gravitate toward the next winner.

I demonstrated my obsession with Tiger baseball during the summer of 1974 by spending hours on the tiny porch of Chickasaw Street wiggling a radio antenna north in order to catch Ernie Harwell breaking down the game from one of the most powerful AM radio stations in the country…the 50,000 watt clear-channel voice of Detroit’s WJR.*

Supplementing all this was the daily Sports section of the Cincinnati Enquirer. While rooting for a particular team or player makes one a fan, “reading” box scores, poring over every team’s rise and fall in the standings, and checking out the leaders in a plethora of wonderful baseball categories made one a fanatic of the game itself. More than any other sport, as George Will reports brilliantly, baseball fans love swimming around in the game’s deep reservoir of statistics and numerical milestones.

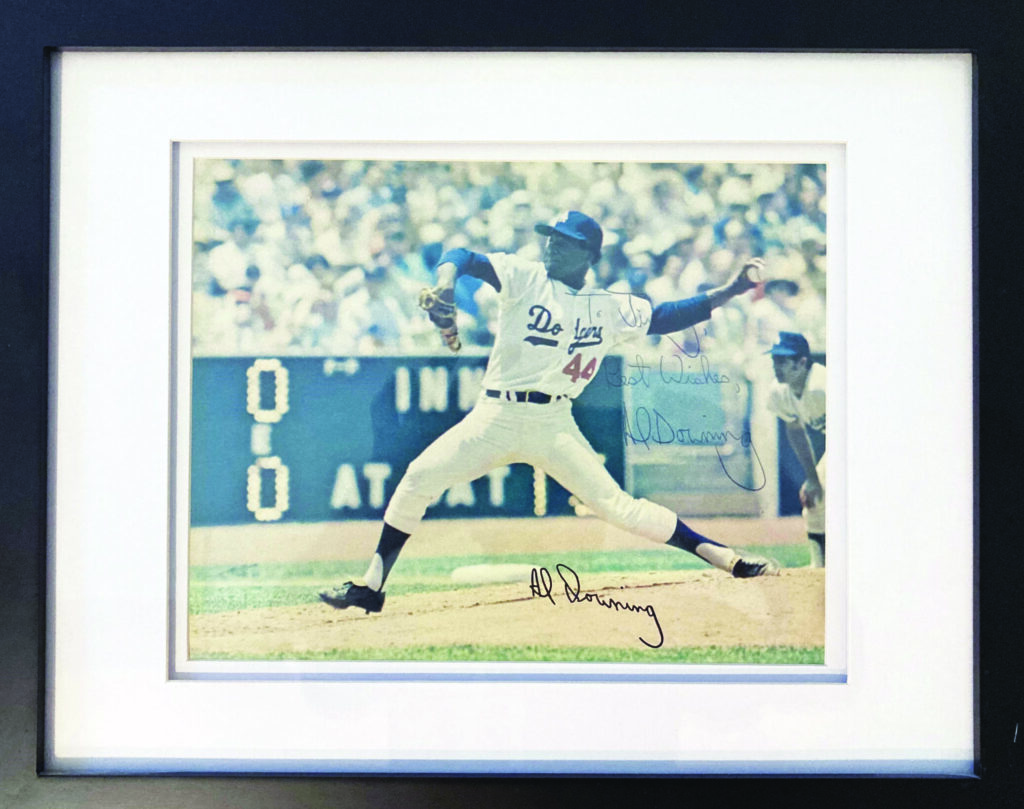

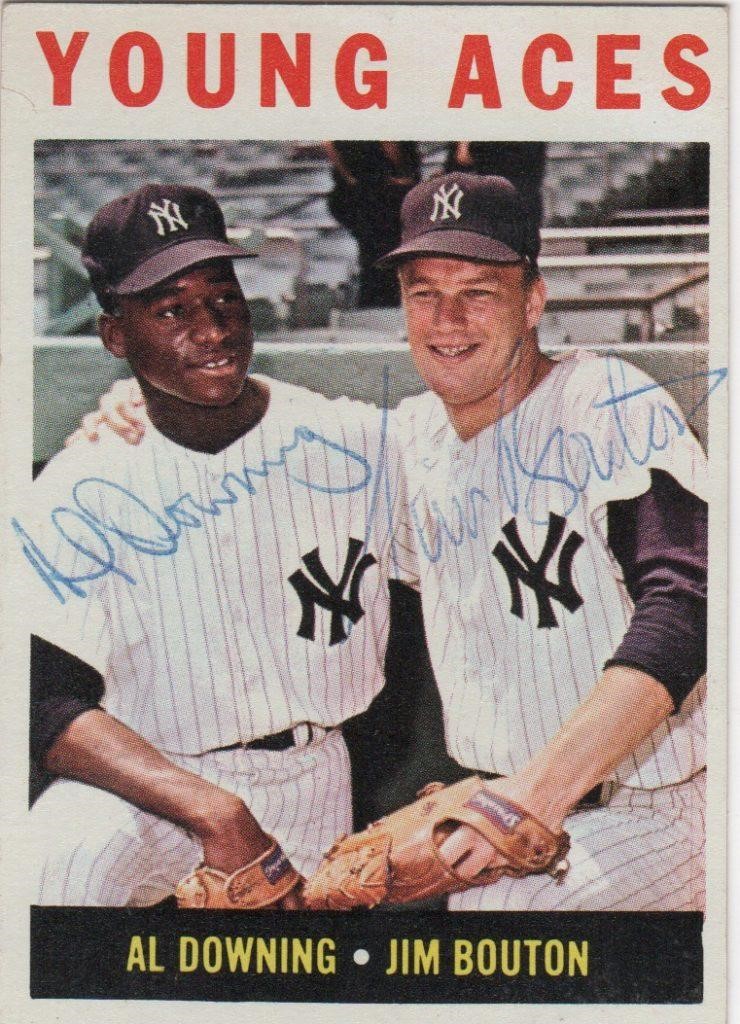

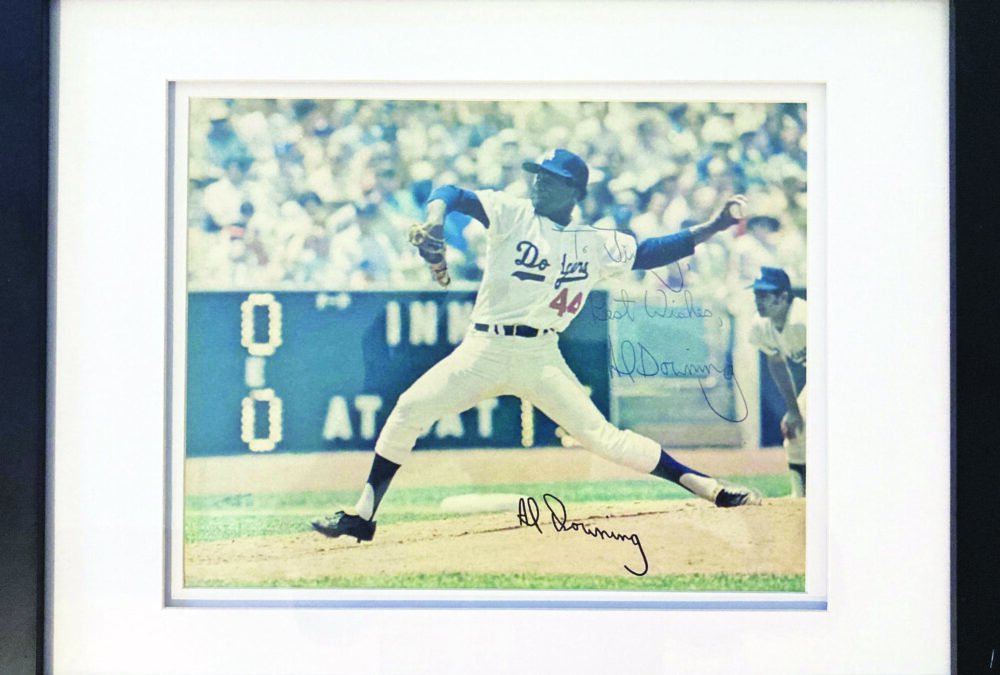

For me, the most important part of this Men at Work-inspired baseball reminiscence is that, during a surreal couple of weeks of that solitary summer of 1974, I was somehow transported to Southern California where I was introduced to Al Downing, pitcher for the Los Angeles Dodgers and a friend of my father’s. Al had a stellar career. He played for the Yankees beginning in 1961 and is seen as their first African-American starting pitcher. In his first year with the Dodgers in 1971, Al became the National League’s Comeback Player of the Year when he won 20 games and led the league with five shutouts.

Meeting Al Downing that summer meant a great deal to me.

After leaving LA and returning home to Cincinnati, I couldn’t help notice that life on Chickasaw Street little resembled my time in Santa Monica, Malibu, and Dodger Stadium. My disappointment was relieved a bit when Al and the Dodgers visited Cincinnati for a three-game series in early September and I took Al up on his invitation to call for tickets.

The Reds and Dodgers split the first two games. On Saturday evening, I made my way to the Dodgers’ hotel. In Al’s room, we were sitting down and watching a little TV before going down to dinner. I made a comment and looked over at my new friend. He was sound asleep. At the time, it occurred to me that baseball, like George Will proposes, is indeed work; and in Al’s case, exhausting work.**

On Sunday afternoon, the Dodgers won 7-4 to clinch a series that would help determine the National League West division champion; a stepping stone for the Dodgers’ appearance the next month in the 1974 World Series where they lost 4 games to 1 to the Oakland Athletics.

While I love baseball and the manner in which it has served as a sort of metric to my life—that I clearly enjoy ruminating upon—I didn’t truly understand The Craft of Baseball until reading George Will’s book.

While examining the technical aspects indicated in his subtitle, Will breaks down the game into four general categories: managing, pitching, hitting, and fielding. Twenty years after writing about the 1988 and 1989 baseball seasons, he described his approach this way: “One can…observe something, be it politics or art or opera or baseball, without comprehending it. Like a novice visitor to a museum or cathedral, I needed a baseball docent.” He found four of them: Oakland A’s Manager Tony La Russa, LA Dodgers pitcher Orel Hershiser, San Diego Padres batting champion Tony Gwynn, and renowned shortstop, Cal Ripken, Jr. of the Baltimore Orioles.

Through the eyes of these craftsmen, it is revealed that their greatness derives only in part due to that which we see on the field. It is their cognitive approach to the game—especially in regards to the manager La Russa—that has them working constantly to gain an advantage in a game that can unfold in an infinite number of possible situations and outcomes. In an environment such as this, baseball, as practiced by its masters, becomes a commitment to exploring tendencies. In doing this, the playing of the game becomes work, and the successful execution of an ultimately predictable scenario becomes a work of art. So, as Will puts it, “taking in” a game, not just watching it, becomes a philosophical endeavor whose purpose is nothing less than the enrichment of the human spirit.

As testament, he invokes ancient Greek philosophers who “considered sport…morally serious because mankind’s noblest aim is the loving contemplation of worthy things…By witnessing physical grace, the soul comes to understand and love beauty. Seeing people compete courageously and fairly helps emancipate the individual by educating his passions.”

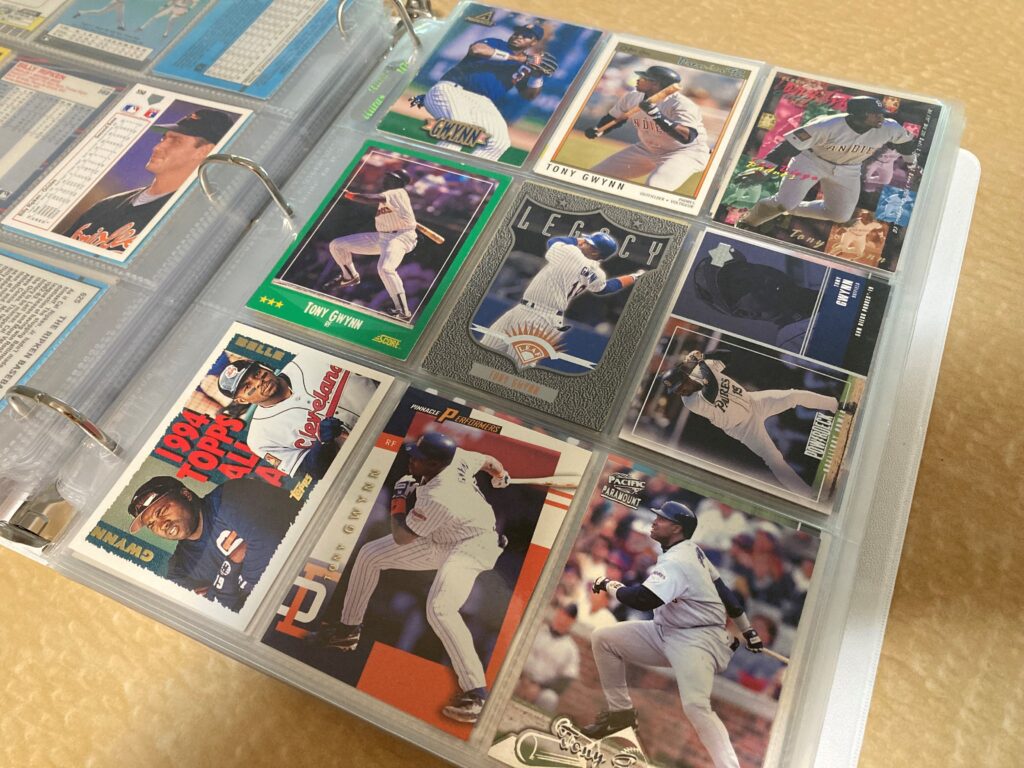

My own passion for baseball includes collecting baseball cards; which is, by the way, the secret of my youthful demeanor. Two of Will’s docents are favorites of mine. Tony Gwyn is one of the greatest hitters of all time; winning eight National League batting titles over a 20-year career, all with the San Diego Padres. The only other player with more batting titles (12 in the American League) is Ty Cobb of the Detroit Tigers who accomplished the feat before 1920. Gwynn’s brother also played in the big leagues which adds to the luster of my Gwynn cards.

Cal Ripken, Jr.—aka Ironman—holds the record for most consecutive games played (2632). That’s over 16 full seasons without missing a game during a career spent exclusively with the Orioles. He also played with his brother Billy while both were being managed by their father, Cal Ripken, Sr. I collect all Ripkens.

Tony Gwynn and Cal Ripken, Jr. were masters of their craft and dedicated to breaking down the game to its finer elements. They are also first-class citizens who were inducted into the baseball Hall of Fame in 2007.

Baseball is methodical and ever-present for those who pay attention. It is also intensively complex for those who play it at the highest level; a point George Will drives home with the rhetorical and literary skills of a veteran political commentator.

In writing Men at Work with his docents to guide him, George Will has become a student of the game. At heart, though, he remains the fan he has always been; baseball took a hold of him at an early age and never let go. As proof, after regaling some of the spectacular baseball moments of 1941—the last full year of baseball before being interrupted by World War II—Will laments that “it was my bad luck to have been born on May 4 of that year, so I missed a full month of the season.” And, in showing off his romantic side, Will designed a wedding ring that “features the MLB logo” because he wanted his wife “Mari to know that in my heart she ranked right up there close to baseball.”

George Will has assumed that readers of Men at Work have a baseline degree of baseball literacy. If you are inspired to read this one and are not familiar with the basics of the game, I suggest reading with a friend who is a fan. You won’t be disappointed.

*Clear channel AM radio stations broadcast over a protected frequency to prevent interference from other signals. At 50,000 watts, WJR—and Tigers baseball—could be heard across the country.

**I would learn later that Al Downing suffers from narcolepsy, a condition affecting sleep and sleep patterns. The only other narcoleptic I know is Sonny, who—during a recreational softball game playing for Dollar Bill’s Saloon in Cincinnati circa. 1981—fell asleep while playing right field. “Wake up Sonny, wake up,” I hollered from first base. Startled, he replied, “I’m awake Jimmy, I’m awake.”

Next article Cap’n Morgan!! I hope you still have your baseball card collection and didn’t have the occasion to visit a pawn shop to pay for other vices 😉