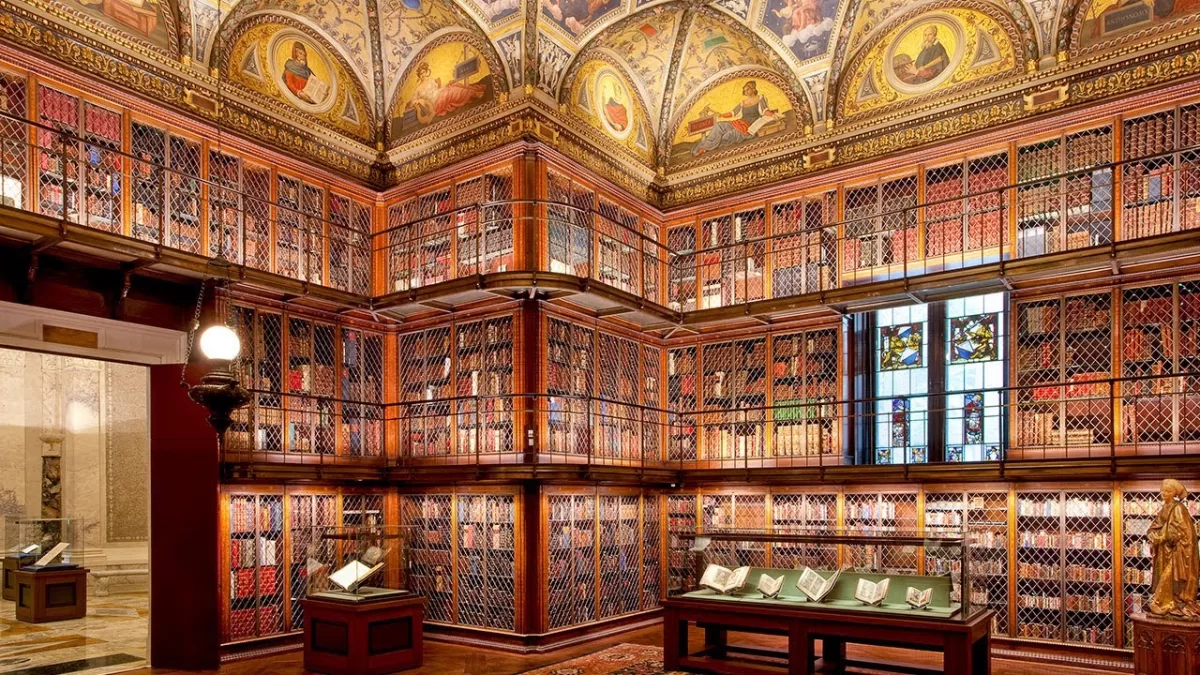

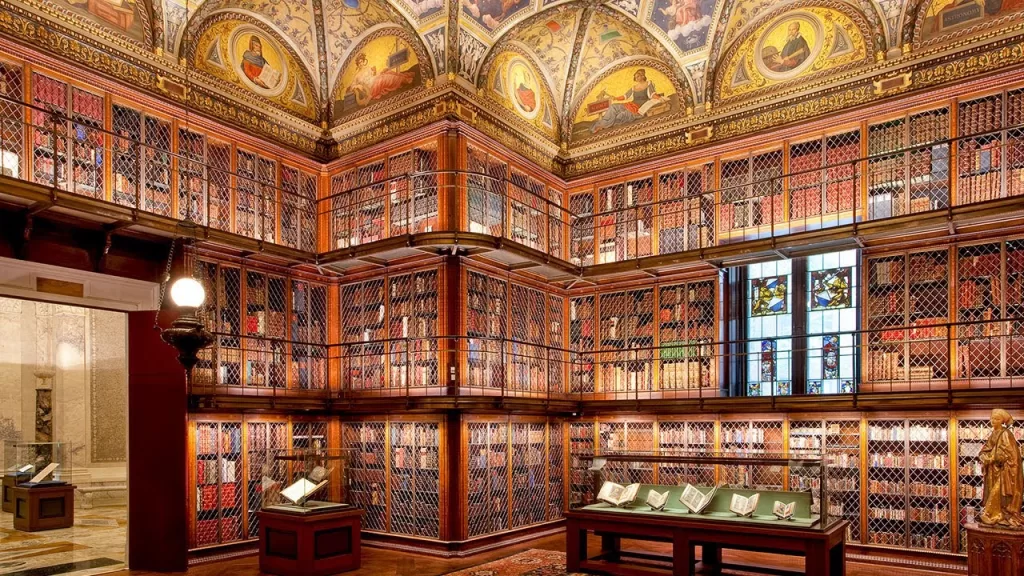

Among his many endeavors, financier John Pierpont Morgan (1837-1913) populated his private library in New York—now the Morgan Library and Museum —with some of the earliest books crafted by the moveable type printing press invented by Johannes Gutenberg in the 1440s.

Being one of the richest men in the world provided the resources to acquire these rare and valuable items, but much of the credit for ensuring the quality and authenticity of these manuscripts goes to Belle da Costa Greene who, unbeknownst to those who admired her most, was African American.*

Greene’s fascinating story is told in The Personal Librarian (2021) by Marie Benedict and Victoria Christopher Murray; a Black and white partnership that has flowered into sisterhood. While clearly settling into the genre of historical fiction, Benedict and Murray hew closely to the known facts of Greene’s widely celebrated life, including her complicated relationship with J.P. Morgan.

Born into an era when the hopes of Reconstruction—embodied in dramatic changes to the US Constitution guaranteeing the equality of the races—gave way to the ravages of racial segregation, Greene invented a Portuguese grandmother to explain away her olive complexion and pass as white.

Greene’s father was Richard Greener, the first Black graduate of Harvard University (1870), and a member of W.E.B. DuBois’ “Talented Tenth,” the small minority of Black men in America at the time with a college education and subsequently, access to a small dose of opportunity in a Black world bereft of it.

Despite the acclaim of her father, Belle da Costa Greene’s decision to pass as white left her in racial limbo. Indeed, as Greene mixed with the upper echelons of American society while developing a global reputation as a collector and curator, acknowledging her father would have destroyed her.

In brilliantly-rendered first person style, Greene says to herself, “I feel like there’s no real place for me inside my father’s world—or in the white one—and I am adrift.” With her race concealed, Greene faces other obstacles in a world dominated by wealthy white men. At one point, while pondering her exclusion from the private Grolier Club which “consists of moneyed bibliophiles whose aim is to promote the scholarship and collection of books,” she reflects, “…as a woman, I’d never be admitted, and to those men, my gender would not be my only sin.”

Within a few short years after being hired as Morgan’s personal librarian in 1905, Greene became his personal representative in the United States and Europe. She used this influence along with her personal charm and daring to acquire highly sought-after manuscripts in an intensely competitive environment. Greene would go on to serve as director of the Pierpont Morgan Library until 1948. After the death of Morgan, she worked for his son, J.P. Morgan, Jr., known as Jack. During that time, Greene oversaw the creation of a national treasure.

Sometimes referred to as simply The Morgan, the library’s website proclaims that, “In what constituted one of the most momentous cultural gifts in U.S. history, [Jack, at Greene’s persistent prodding] fulfilled his father’s dream of making the library and its treasures available to scholars and the public alike by transforming it into a public institution.”**

While the development of the library is an amazing story in itself, Benedict and Murray’s wonderful book explores the curious racial dynamics that seem an ever-present, albeit evolving, characteristic of American life.

In an upscale restaurant, a “colored” waitress holds Greene’s eye for a second longer than might be considered appropriate. It dawns on Greene that this woman—who is also having to participate in the ghastly dance of American racism—is aware of her secret. At first terrified that she is about to be exposed, Greene notices a glint in the eye of the waitress messaging that both of them quietly revel in putting one over on the white man. As throughout much of this engrossing tale, Greene’s inner thoughts, often in stark contrast to her behaviors, propel the narrative. “Why does she serve,” Greene ponders, “while I am served?”

Of course, these inner thoughts are part of the fiction in this historical account, yet they capture what surely must be the sort of things one thinks about in a country so long-obsessed with racially constrictive norms. In another dining scene, Greene reflects upon her conflicted life. “I look up at the colored waiter. I wonder if I have more in common with him than the white world in which I pretend to belong.”

Alienated from her father, in part out of the necessity to preserve her secret, Greene shares his dream of a more just America. She is encouraged to discover that some white people have the same dream. The brother of one of Greene’s white friends asks her if she has read The Souls of Black Folk (1903) by NAACP founder W.E.B. DuBois. While tapping the book, he asks her, “Do you know that this man right here [DuBois] was the first colored man to earn a doctorate from Harvard?”

“In this moment,” Greene is thinking, “I feel a surge of pride and long to tell him about the first colored man ever to graduate from that esteemed school. But I say nothing about Papa as the young man continues on about his love for this book and his hopes for racial equality. I can’t risk it.”

“Reading this,” the young man continues, “has given me such insight into what it’s like to be black in this country.”

“This white man,” Greene says to her inner self, “was born in a place of familial prosperity, but still yearns for equality; my father’s longing stems from a place of survival. It gives me hope.”

Benedict and Murray close The Personal Librarian with a fictional meeting between Belle da Costa Greene and her estranged father, in which Richard Greene imagines the very future that these two authors are writing about. “One day, Belle,” he tells his daughter, “we will be able to reach back through the decades and claim you as one of our own. Your accomplishments will be part of history; they’ll show doubtful white people what colored people can do.”

This is the very reason that books such as these have such power, that impactful and previously neglected stories of the past can help us conjure the idea of a better future. Indeed, in this historian’s humble opinion, making sense of where we’ve been is the essential ingredient in the recipe of creating a more just society.

*Due to the oppressive racial calculus of the day, other language was used to describe non-white people. As the authors write in their historical note, “while these kinds of cultural issues were being addressed and changing in society, Belle was not part of that change, and we felt it would have been difficult for her to see herself and others like her as anything except for the term that she’d grown up using, which was ‘colored.’” This is the term used throughout the book.