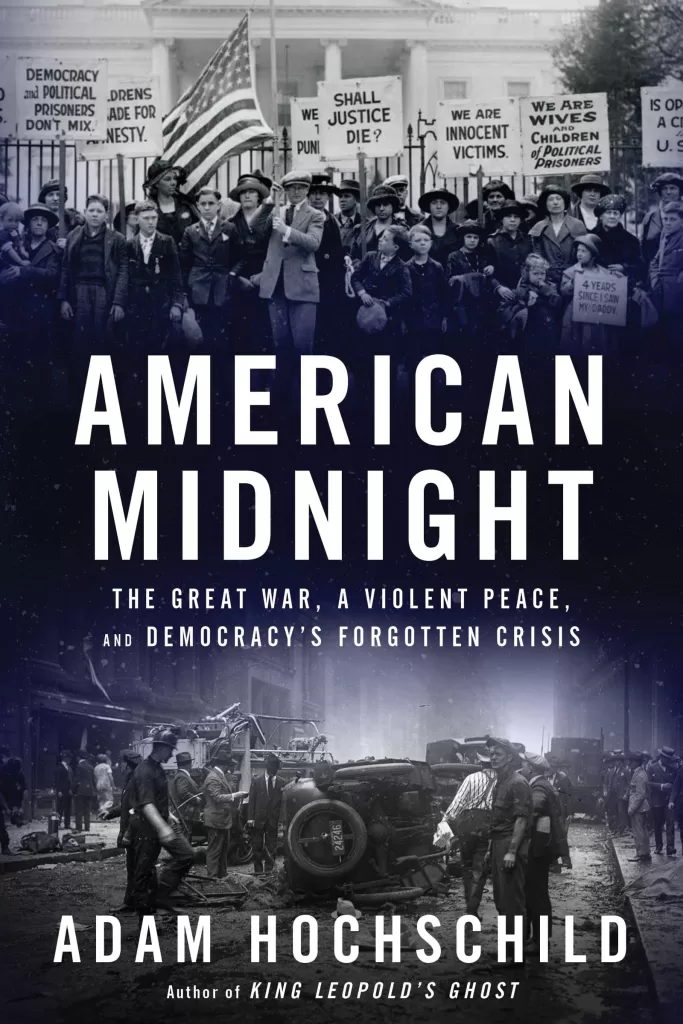

After reading American Midnight: The Great War, A Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (2022) by historian Adam Hochschild, it occurs to me that our nation’s current social, cultural, and political problems are not so much a product of the times we live in as much as they reflect, once again, just exactly who we really are.

This is a troubling thought, I know.

Hochschild’s wonderfully crafted and mind-opening narrative history zooms in on 1917-1921 as World War I gives way to the Roaring Twenties. However, as he points out, while the typical secondary history textbook often takes us from trench warfare and saving the world for democracy to women’s suffrage, flappers, and speakeasies, American Midnight explores the aggressive blowback of this age to two decades of social progress.

Today, far-right conservatives are lashing back against decades of civil rights progress and, even though moderates may not hold the harshest of views, they have become beholden to the demagogic and popularly appealing message emanating from that distant realm. The most outspoken among them blanket their true animosities with elusive language such as “voter fraud,” “woke culture,” and “critical race theory.” Yet, many of their own actual anxieties have deep roots in our nation’s past.

Hochschild brilliantly juxtaposes an eerily similar backlash to the Progressive Era (1890s to 1920 or so) and, in the process, provides a framework for dealing with the exasperating rhetoric of our own day.

Progressive Era reforms addressed the dramatic changes brought about as the country industrialized in the late nineteenth century. Millions of Americans abandoned the countryside in search of opportunities in rapidly growing cities. Beginning in 1910, millions of African Americans began fleeing the terror of the Jim Crow South and made their way to these same cities of the North, Midwest and West. At the same moment, these domestic migrants were joined by millions of immigrants arriving primarily from eastern and southern Europe.

Cities became cesspools of human and animal waste. Millions lived in squalor. Packed tenement houses were rife with rats and other vermin. Fresh water and food were non-existent. With so many laborers to choose from, employers had no incentive to pay decent wages or safeguard work environments. Injured workers were quickly replaced. Children slaved away in factories instead of attending school.

In this era of industrialization and urbanization, a handful of corporations monopolized the production of steel, the extraction and refining of oil, the mining of minerals, the manufacture of consumer goods including automobiles, the expansion of the railroads, and more. And all this took place without regard for the environment. A small handful of wealthy industrialists and an elite class of Americans thrived while millions were crowded into urban slums.

As it should be in a free and just society, trailblazing journalists of the early twentieth century exposed the abuses of corporate monopolies, wildly corrupt political systems, and the massive wealth inequalities they produced. Labor unions organized to protect worker’s rights, often under the banner of socialism.

These “muckrakers” provided the foundation for Progressive Era reforms. Laws were passed to ensure the quality of food, water, and drugs. Others began to address the degradation of the environment. Monopolistic business practices were attacked. Political systems were reformed. Social scientists began to debunk the notion that social problems were the result of bad character and that specific groups were naturally more inclined to commit crime. Rather, these progressives argued that social conditions, and therefore society itself, was to blame.

Now known as World War I, the Great War of 1914-1918 catalyzed the conservative backlash to these progressive reforms.

American Midnight opens within a country debating whether it will enter a war whose violent stalemate over three years had already taken millions of lives under the most horrible of circumstances. 1917 saw President Woodrow Wilson begin his second term in March after campaigning to keep the United States out of the war raging in Europe; only to ask Congress to declare war on Germany on April 2, 1917.

In June, the Espionage Act of 1917 was enacted under the guise of protecting the country in wartime. Unfortunately, the law was used to sew division, stifle free speech, crack down upon “unpatriotic” rabble rousers, and capitalize upon the moment. Speaking out against the war became a crime. Encouraging young men to resist the draft became a crime. “Fear that dissenters might resist the draft, or otherwise thwart the war effort,” Hochschild writes, “provided the excuse for a relentless erosion of civil liberties that American had long taken for granted.”

With President Wilson distracted with foreign affairs and then debilitated by a series of strokes, those around him organized their assault upon the left.

As in our own day, access to reliable information is an essential component of our civil liberties. “Within a day after the Espionage Act became law, [Postmaster Albert Burleson, close adviser to the president] instructed local postmasters throughout the country to immediately send him any newspapers or magazines that looked suspicious.” Periodicals across the country were denied the very lifeblood of free speech, access to the US Post Office.

“In his mind,” Hochschild notes, “some publications were automatically suspect, such as ‘those offensive negro papers which constantly appeal to class and race prejudice.’” Further, “[m]ost of the [questionable] publications that depended on the mail,” Hochschild adds, “were foreign language papers, journals of opinion, and Burleson’s prime target, the socialist press.”

American nativist feeling was exacerbated by the fact that the families of those who had established themselves in this country had come largely from western and northern Europe while the newest arrivals were coming from eastern and southern Europe. These differences were compounded by demagogues arguing that the country was being invaded by “Russians, eastern Europeans, and Jews who were the biggest source of ‘industrial and social unrest and danger…’”

It didn’t help that many of the new arrivals to the country had fled nations that were now at war with one another. And, in this perfect storm of suspicion-generating paranoia, Russian Bolsheviks (communists) took power in November of 1917—setting the stage for the formation of the Soviet Union. The new government then withdrew their troops from Germany’s eastern front, bolstering Germany’s ability to engage with American troops who were beginning to arrive on Germany’s western front. “That this ruthless, relatively small party had seized power in such a vast country,” Hochschild warns, “reignited an ancient American fear of secret conspiracies, something always stronger in unsettled times, when people fear their own positions in life are threatened or eroding and need someone to blame.”

With so many potential enemies, it took little to persuade the American people that something must be done about it; namely, identifying, arresting, and deporting these “threats” to America.

Ralph Van Deman, another close adviser to the president, used his influence within the War Department to create the Military Intelligence Section which developed a comprehensive domestic spy network to uncover subversive behavior within labor unions, ethnic neighborhoods, government agencies, schools, and more.

Professional spies (private detectives) were available for employers concerned about “subversive” behavior in the workplace. At one point, as Hochschild reveals, “the three largest detective firms alone employed 135,000 agents.”

A civilian force was authorized by the US Department of Justice Bureau of Investigation to spy on fellow citizens “[a]nd, for 75 cents, each member [of the American Protective League] received a small silver shield, the size and shape of a police officer’s…” Over 200,000 APL members operated in hundreds of US cities.

With so many looking for so few, tens of thousands of loyal Americans and newly-arrived immigrants were accused of seditious behavior. This far-reaching effort worked its way into the very fabric of American life. Hochschild cites historian David Brion Davis: “The years from 1917 to 1921 are probably unmatched in American history for popular hysteria, xenophobia, and paranoid suspicion.”

While groundbreaking progressives were struggling to address social problems with social science remedies, others fanned the flames of American nativism by clinging to the new “science” of eugenics which stood in defense of an ethnic and racial hierarchy of humanity.

“Just before the First World War,” Hochschild writes, “a prominent eugenicist examined a cross-section of immigrants arriving at Ellis Island and classified 80 percent of Hungarians, 79 percent of Italians, and 76 percent of Jews as ‘morons.’”

Further exacerbating the situation were disagreements over the causes and remedies for the Flu Pandemic of 1918 which claimed over 50 million lives across the globe; with over 600,000 deaths in the United States.

Disturbingly, as the American military prepared for civil unrest, “they were not worried about the ‘relatively large’ Black citizenry in the South, because ‘this danger is well understood and the white population in these regions can be counted on to control the population.’” Indeed, many of the tactics used by white supremacists were now being deployed against other “undesirables.”

At one point, those within Military Intelligence “portrayed their enemies as numerous beyond imagining… as they calculated that the country contained, among other dangerous groups, 914,854 Socialists, 322,284 Red radicals, and an alarming 2,475,371 ‘unorganized Negroes.’”

Apparently, the number of socialists cited in this report roughly equals the number of Americans who supported socialist Eugene V. Debs during his runs for the presidency in 1904, 1908, 1912, and—while in prison for sedition—1920. “[W]here the other numbers came from,” Hochschild quips, “no one knows.”

In 1905, Debs helped found the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), commonly referred to as Wobblies. Labor unions were targeted throughout the Progressive Era and, in 1917, under the authority of the Espionage Act, the US Justice Department, led by Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, engaged in an aggressive campaign, including a number of widespread crackdowns now known as the Palmer Raids, to destroy the union by arresting and jailing thousands.*

In a nod to our own problems today, Hochschild describes Palmer as “a demagogue who believed his own demagoguery.”

Despite the severity of these problems, Adam Hochschild offers up the hope that in difficult times such as these (and those), courageous people step up; often suffering personally for doing the right thing.

As I mentioned, socialist Eugene V. Debs was a candidate for president while officially recognized as Prisoner #9653.

Senator Robert La Follette of Wisconsin openly criticized America’s entrance into World War I and defended the rights of working people; the type of speech that put many Americans in jail. While characterized as a traitor, La Follette is now viewed as one of the greatest senators in US History.

Russian-born anarchist Emma Goldman was rounded up in the Palmer Raids and was convicted under the Espionage Act for encouraging resistance to the draft. She was sentenced to prison, fined, and then deported following her release.

Women struggling for the right to vote were also seen as dangerous. “In the eyes of millions of American men,” Hochschild writes, “ambitious women were as much of a threat to the traditional order as immigrants, socialists or Blacks.”

As the Assistant US Secretary of Labor, Louis F. Post defended the rights of immigrants and opposed efforts at mass deportations. He defended free speech and railed against the abuses of the Espionage Act. As one contemporary supporter said of him, “the name of Louis F. Post will be given a high place, because he dared in a trying time to defy the forces of madness and hatred and greed that now threaten to overwhelm us.”

American Midnight offers up many similar stories of those who pushed back against “the madness” reminding us that there are those among us today doing similar work. Reason has a way of reasserting itself, Hochschild suggests, if only a few principled and intrepid individuals stand firm.

Also clear is that the struggle will continue because, in times of strife, a great number of us tend to become susceptible to the ranting and raving of demagogues who speak of an America “under God” as it was “meant to be.”

In turn, these demagogues quickly convince many who feel threatened that there are “others” who are responsible for all that is wrong.

Inevitably, these “others” have easily identifiable characteristics of appearance and behavior that draw a stark line of demarcation between “us and them.”

In fractious times, the truth gets turned on its head, rational conversation disappears, and the very nature of reality—for many—is subsumed by the outrage of sloganeering profiteers.

Today, we are beginning to see the weakness in the far-right arguments that have so enraged a significant portion of the country; yet, not without the courage of a handful of individuals who have publicly stood up against the madness.

It can’t hurt, either, for all of us to understand that this has all happened before. Good history informs the present. Great history offers hope. American Midnight does both.

*This is a fascinating website dedicated to the Wobblies and the lengths those in power will, and the unseemly tactics they will deploy, go to prevent labor organizing. https://depts.washington.edu/iww/justice_dept.shtml