Pirates Cove in Malibu is small and isolated—a crescent of white sand surrounded by forbiddingly steep cliffs. It faces the open ocean. This storied stretch of coast is said to have been named not for the “avast ye me hearties, walk the plank” variety of pirate, but for the smugglers who ran alcohol, drugs and sometimes trafficked human beings during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

As recently as the 1950s, this remote and sheltered cove was home to a colony of sea lions. By the 1960s, it had become a colony of an entirely different sort: a gathering place for nudists. That was a problem, but perhaps not for the obvious reasons.

This odd chapter in local history is one of the things I get asked about most often, and part of the material in this article appeared in print in my 2020 book, Life in Malibu II, but there is more to uncover.

The naturism movement—not to be confused with naturalism—evolved in reaction to the excessive modesty of the Victorian period. In America, it became a revolt against repressive mid-century modern conformity, and part of the new health and fitness movement that embraced the idea of getting back to nature. By the 1960s, it had become part of the Civil Rights movement, and it found the ideal climate to thrive in the local canyons and beaches.

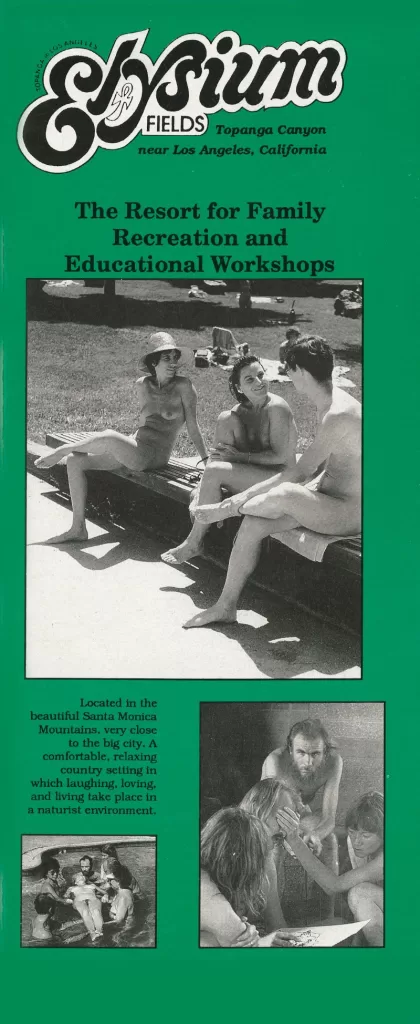

In 1969, Irwin Lange, known as Ed, established Elysium Fields, a clothing optional resort on seven acres of the old Dutton Ranch in Topanga Canyon. The resort defied a 1939 countywide ban on nudism. Lange’s civil disobedience was inspired in part by nudism advocate Lura Glassey, who tried to take the fight to the Supreme Court a generation earlier and failed.

Lura, a home economics teacher, her husband Hobart Glassey, a psychoanalyst, and their friend, Pete McConville, a former grocer, met while working at a clothing optional camp in upstate New York in the early 1930s. They came west in search of better weather, and opened a nudist camp called Elysia in Riverside County. It was swiftly shut down by the Riverside County Sheriff and District Attorney.

A year later, the trio acquired 330 acres in what is now the Cleveland National Forest. They created a second camp, and eventually settled their differences with the local officials. The Glasseys left in 1935, but McConville stayed on, renaming his club the Olympic Fields. It remained in business under a succession of names until 2007.

Lura Glassey had a rougher time of it. She and her husband moved to Los Angeles County and founded a new club for nudists—Fraternity Elysia—in Sun Valley, but her husband died in 1938, and Lura faced a constant battle with law enforcement. She was arrested multiple times for violating a newly created Los Angeles County law that prohibited nudism. In 1946, a sting operation resulted in Lura being sentenced to 180 days in prison. She wasn’t without friends—her supporters included Charles Richter, the CalTech scientist and professor who invented the Richter scale for assessing the magnitude of earthquakes—but the legal costs mounted. The Supreme Court declined to hear the case in 1947, and Lura Glassey was forced to sell Elysia.

Ed Lange followed Lura Glassey’s legal fight with interest and indignation. He had become an enthusiastic supporter of nudism in his teens, after encountering a magazine that promoted the lifestyle. Lange threw himself into the legal battle over nudity. A successful fashion photographer, he became a publisher, printing books and magazines promoting the naturist lifestyle. Like Lura Glassey, he faced lawsuits, but he also filed many of his own. One lawsuit resulted in a 1956 U.S. Supreme Court decision that enabled nudist publications to be sent second class mail; another persuaded Eastman Kodak to develop prints featuring nude subjects, instead of confiscating the negatives and refusing to print or return them.

When Lange opened the Elysium Fields in Topanga, he was arrested and charged with indecent exposure. He didn’t let it stop him.

The Elysium Fields was a rather austere place, with a focus on clean living and fresh air. People went there to play tennis, go swimming, and sit in the sun, not to participate in orgies—sex was verboten—but that didn’t stop puritanical Los Angeles County officials from trying to shut the Lange down.

It didn’t help that the Elysian Fields was often confused with a nearby ranch where orgies really were the order of the day. The Sandstone Foundation, up by Saddle Peak, was inspired by the writings of Ayn Rand. The founders, a husband and wife team, believed in open relationships and sexual experimentation. The ranch attracted the interest of New York Times journalist Gay Talesan, and gained national attention in his book Thy Neighbor’s Wife, an exploration of the sexual revolution in America.

Elysium Fields attracted plenty of media attention, too, and Lange used the publicity to promote the nudist lifestyle. He actively campaigned not just for private facilities, but for clothing optional public beaches, where naturists could sunbathe au naturel, undeterred and undisturbed.

One of those beaches was Pirates Cove. In the early 1970s, the county acquired Westward Beach and built a new parking lot. That made Pirates Cove less remote, although it was accessible along the shore only at low tide, and the headlands that had to be crossed to reach the cove at any other time were private property.

Pirates Cove is familiar to film buffs as the location of the dramatic denouement of the original 1968 film Planet of the Apes, but it remained the domain of solitude seekers and the few remaining sea lions—the species had a close call with extinction in the 1960s—until it became a destination for nudists.

This was before the era of social media, but word spread that Pirates Cove was a clothing optional beach and crowds descended: nudists, and voyeurs ogling the nudists, gathered in the hundreds in the small cove, and on the fragile cliffs above it. A county ordinance banning nude bathing was passed in 1974, but it only added fuel to the controversy. The nudists were now facing opposition not just from conservatives, but from conservationists.

Point Dume residents found themselves living in a Monty Python sketch. Nude beachgoers wandered around the residential neighborhoods seeking alternate routes to the beach. Nude rock climbers were routinely rescued from the cliffs, attempting to clamber down to the beach from above. The Sheriff ’s report section of the Malibu Times and the new Malibu Surfside News were full of confrontations involving nudists—one of them wearing a beef steak around his neck (eat your heart out Lady Gaga), another armed with a hatchet.

The controversy around the nudists and the crowds they generated eventually threatened to derail the complex and delicate negotiations underway to buy the headlands, including Pirates Cove, for the state.

The property belonged at the time to developer Roy Crummer, Jr., a major Malibu landowner who had plans to build a hotel above the cove. Although the recently passed Coastal Act made it legal for the public to be on the beach below the mean high tide, there was no way to get there when the tide was in except over private property. The argument was made that the hotel proposed by Crummer would be less damaging to the environment than a public beach, because once the hotel was built the public could be kept off the bluffs.

That argument gained traction after a 1978 protest attracted more than a thousand people to the cove, a place with no restrooms or trash receptacles. One volunteer still recalls the clean-up effort after that 1,000-nudist flash mob went home for the day, she says the mess was “indescribable.”

Ultimately, the state purchased the headlands in 1979, undeterred by the controversy. Pirates Cove was closed by the county in 1980, ostensibly to help it recover from extensive ecological damage, but the closure was overturned and the nudists returned.

The state’s response was a plan to pave the top of the headlands, to make it easier for the crowds to park. The nudists continued to push for official recognition, lobbying for Point Dume and seven other beaches, to be designated clothing optional. In response, the county began enforcing its anti-nudity laws. Once sheriff ’s deputies started writing tickets the number of nudists decreased significantly.

In 1994, the U.S. Supreme Court had the final word: nudity is not a Constitutional right. “Better not bare your bottom at the beach,” the Los Angeles Times quipped following the ruling.

The losers of the Malibu fight over public nudity were the sea lions. The rookery was never reestablished. The species is a conservation success story statewide, and sea lions still haul out on the rocks near Pirates Cove, but the local colony gives birth in the safety of the Channel Islands, not on the beach.

Thanks to local opposition, the parking lot plan was abandoned. The park, now the only undeveloped section of coastal bluff in the area, was given new protections as a nature preserve in 1992, the same year that Malibu finally became a city.

Lange lost the fight over beach use, but he continued to battle the county. The same year Pirates Cove became part of a nature preserve, Lange won his fight with the county over the Elysium Fields, and was finally issued a permit.

Lange died in 1995. The Elysium Fields closed in 2001. It remains part of Topanga’s colorful, countercultural history, but it is also part of a complex tangle of civil rights issues that are still in play. Anti-nudity legislation is used in many places to prohibit women from breastfeeding in public. New laws that ban activities like drag shows echo the language of laws prohibiting nudity.

In 2002, Attorney General John Ashcroft spent $8,000 on draperies to clothe a pair of Art Deco statues in the Great Hall of the Justice Department. The AG was uncomfortable giving press conferences in front of the naked breast of the Spirit of Justice. The drapes remained for the rest of Ashcroft’s tenure—three years. They were a gift for late night talk show hosts, but they also revealed more than they covered: a pervasive, puritanical discomfort that runs deep in certain religious and political circles.

Former Vice President Mike Pence, who is running for president in 2025, famously avoids dining with or even being seen in public with any woman who is not his wife. Is that because men and women can’t be trusted to behave, or perhaps because under their clothes, everyone is naked…?

It’s cold out there. Don’t forget your sweater.

Heard Sir Francis Drake was the pirate the cove was named for, hiding behind the point to attack the Spanish ships, loaded with treasure from the Philippines, that were headed down the coast.