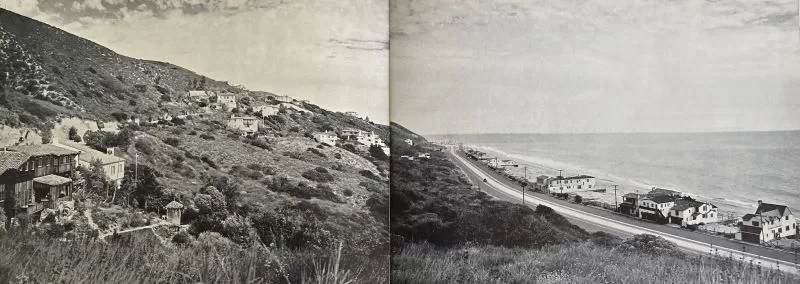

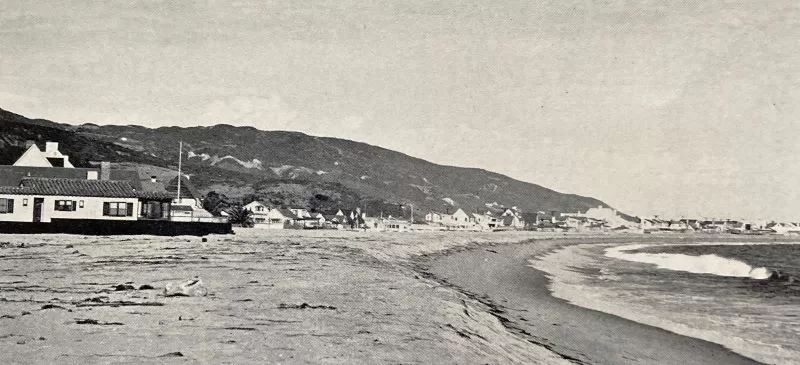

La Costa Beach is almost entirely hidden behind the houses that locals have nicknamed “the Great Wall of Malibu.” Also hidden here, among the homes that line the coast and cover the hillsides, is a colorful chapter of local history that takes place in the financially reckless Roaring ’20s—it’s a plot that could have come straight from a silent-era movie script.

In the 1920s, May Rindge, the last sole owner of the Topanga Malibu Sequit Rancho, contracted with real estate developer Harold G. Ferguson to subdivide and lease the Malibu Colony and build the La Costa Beach neighborhood. May was reluctant to part with even this small portion of her 17,000-acre Malibu ranch, but she needed the money to help defray the cost of litigation over the state’s plan to build what ultimately became Pacific Coast Highway on her property.

May took the fight to keep the highway off of her land all the way to the Supreme Court, and lost in 1923. She tried a variety of projects to make up the money she had spent during the lengthy legal battle and the amount she increasingly owed in taxes. For a time, it seemed that oil would be the answer, but no oil was found. One of May’s successes was the Malibu Potteries, established in 1926. The workshop used native Malibu clay to craft decorative art tiles for the burgeoning building boom in Los Angeles. It was a successful enterprise, but it wasn’t enough to keep Rancho Malibu afloat. May decided the only option was to dip into the ranch’s real estate potential. Her initial plan was to lease, not sell, some land.

The same year she established the potteries, May contracted with Ferguson to build and lease small summer cottages on the spit of land west of the Malibu Lagoon. Ferguson envisioned a Malibu Movie Colony that would attract film stars and Hollywood money and he had the connections to make that vision a reality.

Ferguson was born in Canada in 1888, but he grew up in Southern California. After serving as an officer in WWI, he went into the real estate business in the post-war boom years. He had already made a name for himself as a respected member of the business community when May Rindge contracted with him for her Malibu Rancho projects. Ferguson’s first major development project was a 258-acre subdivision in the Wilshire-Fairfax area of Los Angeles. In 1928, he was named the head of the Executive Committee of the Better Business Bureau of Los Angeles, and in 1929 he was elected president of the Los Angeles Realty Board.

May’s Malibu Colony development agreement with Ferguson stipulated that the buildings would be temporary in nature, so that May could have them removed if her fortunes had changed at the end of the 10-year lease period and she no longer needed the rental income. Ferguson succeeded in attracting Hollywood names and money, and the development—a row of quirky bungalows built, according to local tradition, by studio set builders—helped generate much-needed income for the ranch, but it still wasn’t enough.

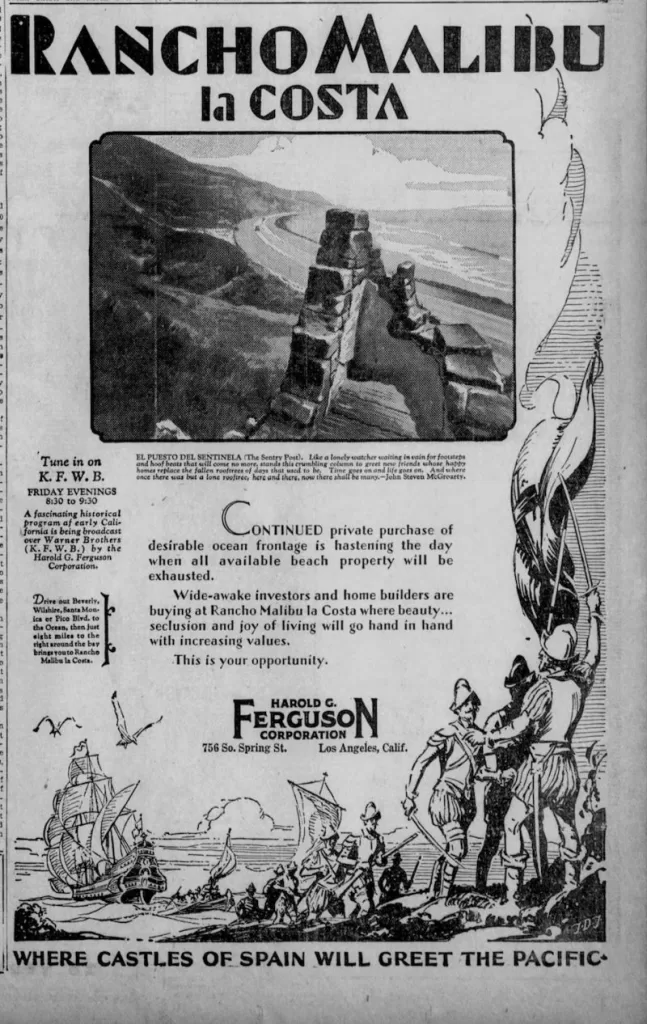

In 1928, May’s Marblehead Land Company negotiated to sell 593 acres of the Malibu Rancho east of Carbon Beach and west of Las Flores Canyon to the Harold G. Ferguson Corporation for just under $5 million.The sale included 7,500 feet of coastline. A deposit of $995,000 was paid by Bank of America in March of 1929. Ferguson began planning a “Riviera by the sea,” with houses in a Spanish-colonial fantasy style, and an exclusive beach club. He gave the streets Spanish names like Rambla Pacifica, and Paseo Serra, and began building not only houses, but imitation Spanish colonial ruins to add a bit of Ye Olde California Mission atmosphere to the development.

Ads for La Costa, featuring riders on horseback and beautiful young models posing amongst the picturesque and completely bogus ruins, traded heavily on the romance of Malibu’s history as an original 1804 Spanish land grant. Ferguson even gave radio talks on the history of La Costa—history he invented. He described the barracks that housed Spanish soldiers and fiestas held on the beach in loving and completely fictional detail.

In a 1929 promo piece in the Los Angeles Evening Citizen News, Ferguson describes “a scene 150 years ago of eventide gatherings beside a warm fire where the grapes gathered from the nearby hills were crushed and the juice stored in the making of the first California wines.” It was an activity that would have astonished the Chumash people who were the only residents of the area in the 1770s.

Ferguson even enlisted the talents of writer and poet John Steven McGroarty, a future California Poet Laureate who would also go on to serve two terms in Congress. McGroarty had plenty of imagination and no scruples over rewriting California history. He was happy to wax rhapsodic over Ferguson’s revisionist ruins and their equally inauthentic provenance.

In the same way Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind helped popularize and sanitize the antebellum South, Ramona, a 1884 bestseller written by Helen Hunt Jackson, romanticized the California missions and Spanish-Mexican colonial culture. Ferguson was attempting to cash in on the fad (so was May Rindge, with the beautiful Spanish and Moorish-style tiles produced at the Malibu Potteries).

The big advertising push for La Costa took place right before the catastrophic stock market crash that kicked off the Great Depression. La Costa, with its large, permanent and more costly houses, was a harder sell than the small, quirky cabins on the beach at the Malibu Colony. Unlike the secluded Malibu Colony, La Costa was bisected by the newly opened Roosevelt Highway. Sales were slow. Plans for building a yacht harbor and improvements like a private tunnel under the freeway to make it easier to safely cross the busy highway were put on hold, not just because of the challenging financial climate, but because Ferguson was headed not for fame and fortune in the Southern California real estate market but for a cell in San Quentin.

Ferguson’s Malibu Syndicate was just one of many he set up to fund the purchase and development of real estate throughout Southern California. The Harold G. Ferguson Corporation was also responsible for subdivisions at Lake Arrowhead, and Beverly Crest, among others.

Ferguson used his real estate company to create investment trusts for each project and then sold beneficial shares to investors to fund the purchase and development of the real estate. This allowed people to invest small sums of money in return for dividends, but it also opened the door for potential criminal activity, the kind that landed Charles Ponzi on the front pages and in a federal penitentiary in 1920. Ferguson’s approach to financing eventually attracted the attention of the California Corporations Commission.

The commission found that Ferguson was purchasing shares in one trust with funds from another and using the proceeds to show impressive dividends, as an inducement to attract new investors. Ferguson was found guilty on nine counts of violating the Corporate Securities Act and 10 counts of grand theft. The La Costa development was one of the swindles that sent him to prison. He was sentenced to nine years, and served three years and three months in San Quentin.

May Rindge’s Marblehead Real Estate Company was able to reclaim the title for the La Costa land, but the investors in the project weren’t as lucky. They were denied the recovery of $443,000 from the Bank of America National Trust and Savings Association and May Rindge’s Marblehead Land Company, the third-party companies Ferguson used to broker his Malibu deals.

Construction at La Costa moved forward without Ferguson, but at a much slower pace. The private La Costa beach club is still there, but the tunnel under the highway and the yacht club were never built. The scattering of houses Ferguson completed attracted solitude seekers, rather than the social set. The most famous resident was arguably Malibu’s first unofficial mayor, writer Edgar Rice Burroughs, the creator of Tarzan. In 1931, he bought one of the first beach houses constructed by Ferguson and lived and wrote there for nearly a decade. When Burroughs moved to Malibu he had few neighbors and a nearly 360-degree vista of unspoiled beach and mountains. Growth came slowly.

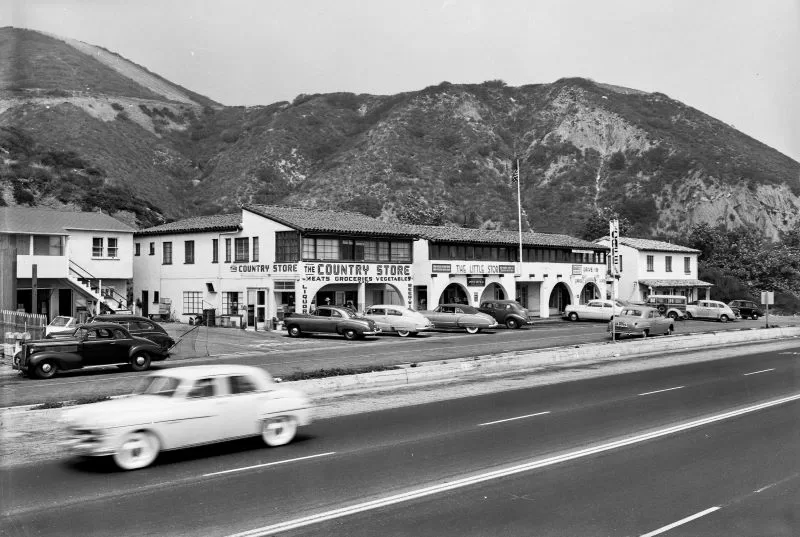

La Costa became home to the area’s first telephone equipment in the early 1930s, and to Malibu’s first gas station. The Olas Grandes Inn, a restaurant that was built in the late 1920s and was the first commercial building at La Costa—designed to cater to travelers on the newly constructed Roosevelt Highway—became a small shopping center, with groceries, a beauty shop, and Malibu’s first post office. The Spanish colonial-revival style Malibu Courthouse was completed in 1932. It was designed by the architectural firm Butler & Butler and lavishly decorated with Malibu Potteries tiles. It remained a county courthouse until the 1970s, when the Malibu Civic Center complex was constructed. The building is still there, but it stood alone for decades.

In 1934, a Court of Appeals reversed one of Ferguson’s 10 grand theft charges and all of the securities charges. He was pardoned in 1939 by California Governor Frank Merriam, but continued to face civil suits from investors seeking to recover their money. He died in 1963.

May Rindge’s expenses continued to mount. She sold the lots she had leased in the Colony, but once again, it wasn’t enough.

The Marblehead Land Company filed for bankruptcy in 1936, and the vast Malibu Rancho was divided into parcels and put on the market, but the sale of the land was impacted first by the Depression and then by WWII. The U.S. government closed the coast and commandeered Point Dume for the military from 1942-1945. Fear of imminent attack and the shortages of gas, tires, and automobiles turned Malibu into a ghost town during the war, and it wasn’t until the early 1950s that the next building boom began. May didn’t live to see her personal kingdom by the sea fully dismantled and sold off. She died in 1941, just before the U.S. entered the war.

After the war, the empty lots in the La Costa development gradually filled in, creating a patchwork of house styles. This community was hit hard by the 1993 Old Topanga Fire. Today, its architecture mostly reflects the post-fire recovery period, but the old Olas Grandes Inn building is still there. So is the former courthouse, and there are still a few of the original houses built in the late 1920s, including the home where Edgar Rice Burroughs lived, one of the first houses built on the beach. It’s a relic of the boom and bust period of Malibu in the 1920s— a silent era crime drama, complete with dramatic backdrops, a romantic backstory, and a cast of colorful characters.

Hello, I hope you are well, I wanted to check in and hope your home is not gone from the fires.