The Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area is turning 45 on November 10, 2023.

Almost all of the big western national parks were created from huge areas of undeveloped wilderness, but this living crazy-quilt of a park—spread across 153,250 acres and 26 zip codes in two counties on the edge of one of the most densely populated urban areas in the country—has had to be pieced together, a patchwork made from fabric acquired one square at a time by federal, state, and local agencies. It is quilted together by the National Park Service, the agency that oversees the entire area. The SMMNRA is now considered to be the largest urban national park in the country and probably the world, and it continues to grow, piece by piece, against all odds.

When President Jimmy Carter signed the SMMNRA into law in 1978, the National Park Service did not yet own one single acre in the Santa Monica Mountains. Creating this park was an almost impossible task, but that didn’t stop passionate activists from persevering in the face of the impossible.

Topanga was at the center of the push to create a local National Park from the beginning. Some of the most ferocious environmental fights over open space were fought to save what is now 11,000-acre Topanga State Park. Even today, when Topanga is part of the bigger 153,250-acre Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, this community remains in many ways the heart of the mountains.

The earliest effort to create a national park in the Santa Monica Mountains started in the 1920s. Sylvia Morrison, an early environmental activist who lived in Pacific Palisades, lobbied for the creation of “Whitestone National Park,” after real estate developer Alphonzo Bell proposed using dynamite to create a limestone quarry in Trailer Canyon (sometimes spelled Traylor). Morrison led hikes into the canyon, and encouraged the public to discover the area’s natural beauty.

“Our heritage of the hills must not be wasted,” Morrison stated at a 1928 hearing. The opposition she spearheaded attracted the support of Will Rogers and silent filmmaker Mary Pickford. The quarry plan was stopped in 1930; but the Depression put an end to her proposal for Whitestone National Park.

Topanga was the flashpoint again in 1963, when county planners began pushing for a massive development spread along the ridge lines from Topanga to Sullivan Canyon.

The Mountain Park development proposed ten “village centers,” housing more than 60,000, spread over more than 11,000 acres of previously undeveloped mountain terrain. More than half of the development would be in Topanga. The quiet mountain community of 3,000 would balloon to twenty times its size under the plan. To connect those “village centers” a six-lane freeway was proposed for winding, narrow, unpaved Mulholland Highway.

Celebrated Los Angeles architect William Pereira was brought in to design the project. Pereira designed the Los Angeles County Art Museum, Marineland in Palos Verdes, and the entire master-planned community of Irvine. He had a theatrical flare and a fondness for science fiction. A Los Angeles Times article on Pereira’s Mountain Park plan described “facilities concealed in architectural caves in the steep canyons,” and “cascade housing built into the hillside itself and served by ‘inclinators,’ [that will] take the place of high rise apartment towers.”

Pereira’s plans may have been impractical, but he possessed something the developers who hired him did not: an appreciation for the natural beauty of the mountains. His original plan was intended to take advantage of views and include greenspace. It was soon clear to him as well as to the people opposing the project that the developers had no intention of leaving anything unbuilt. This wasn’t the “city of the tomorrow” envisioned by the architect, it was high density development on a massive scale—the most destructive kind of urban sprawl.

“The impetus for this development has come chiefly from developers and not from residential property owners along the proposed route,” Los Angeles City Councilmember Tom Shepherd told the Los Angeles Times in an October 8, 1963 interview. Shepherd opposed the plan, but other officials in the county and the city were avid supporters of the proposal, and pushed hard for the development.

Topanga pushed back. A small group of residents-turned-activists founded the Topanga Association for a Scenic Community (TASC) in October 1963, shortly after the plans for Mountain Park surfaced. The group included architect Bob Bates and his wife Donna, architect Willian Earl Wear, actress and Topanga luminary Herta Ware Geer, and psychology professor and Holocaust survivor Herbert Gutman. TASC filed lawsuits, wrote letters, organized protests, and lined up volunteers to make the trek into downtown LA to speak at meetings. The volunteers gathered more than 10,000 signatures opposing the plan and advocating for the creation of a real park, but it would take almost ten years for that vision to become a reality, and the conservation battles were unending.

Just weeks after TASC was formed, its members entered another conservation battle, this time joining with the Santa Monica Canyon Civic Association in opposing the Santa Monica Causeway: a plan to build a man-made isthmus in the Santa Monica Bay extending from Olympic Blvd. in Santa Monica to Topanga Beach. An eight-lane freeway was planned for the causeway, connecting Santa Monica to Malibu. The freeway would be lined with housing tracts, shopping centers and marinas, built on almost 100 millions tons of fill created by flattening the mountains to create more space for housing tracts.

Mountain Park and the Causeway were among the most extreme threats to the local environment, but Topanga activists faced an epidemic of high density development projects. TASC continued to battle plans for everything from Sunset Mesa-style cut-and-fill tracts with hundreds of homes, to an entire city complete with an airport, and a plan to channelize Topanga Creek and build condos in the lower canyon.

Other communities throughout the Santa Monica Mountains were also facing major development issues. Pacific Palisades ended up with the actual Sunset Mesa, a 500-residence tract development built in 1962 on ecologically sensitive Parker Mesa.

Rapid development in the Conejo Valley threatened to turn tens of thousands of acres of ranch land and oak-covered hills into a sea of tract developments like the San Fernando Valley, including hundreds of houses and condos at what is now Paramount Ranch Park.

Malibu was not only fighting the causeway, but also a plan to build a six lane freeway down Malibu Canyon, along the beach, and through the heart of the community. Activists there were also battling two Marina Del Rey-style yacht harbors, the County Board of Supervisors’ vision for a Miami-style beach city of more than 160,000, and even a nuclear power plant—located on top of the Malibu Coast earthquake fault.

The Malibu Township Council, a community activism group founded in 1947 to combat an early plan to build a yacht harbor in the Malibu Lagoon, became the model for many other local community organizations. The modus operandi is simple but time-consuming: attend every meeting, review every planning document, find all of the things that violated zoning laws or environmental protections, make sure those issues are addressed, file legal action if they aren’t, and—most importantly—keep at it and don’t give up, even if it takes years.

The Santa Monica Mountains were already recognized as a rare and important Mediterranean ecosystem and a biodiversity hotspot, but there were few protections, and those protections were often ignored. Conservationists, beginning with Sylvia Morrison, reasoned that a national park would provide federal protections in an area that was becoming an out of control development free-for-all. The problem was, there wasn’t any public land to use as a starting place. That began to change in the 1950s.

The state established Leo Carrillo State Park in 1953, after purchasing 1,200 acres of coast and canyon at Arroyo Sequit on the edge of Ventura County. The park would soon grow to 2,513. It was followed by the first 6,700 acres of the historic Rancho Guadalasca/Broom Ranch in Ventura County in 1967, now Point Mugu State Park. Critics argued that those two parks weren’t enough to warrant creation of a national park, but conservationists continued to try. Alphonzo Bell, Jr., son of the quarry developer and an eight-term member of Congress, introduced the Toyon National Park bill in 1971. It didn’t pass.

An additional 5,800 acres was added to Point Mugu State Park in 1972, nearly doubling its size. The state acquired 3,700-acre Century Ranch—now Malibu Creek State Park, the same year, although the deal stipulated that the land be leased back to 20th Century Fox for three years before opening to the public.

In 1974, after the Mountain Park plan finally collapsed under pressure from activists, 11,525-acre Topanga State Park was finally added to the roster of public lands. There was enough public land to quell the loudest argument against a national park, but there was still opposition. Bell tried again in 1976, with legislation to create the Santa Monica Mountains and Seashore Urban National Park. That bill also failed to gain traction, but it helped to provide the impetus for the final effort.

Three activists: Sue Nelson, Jill Swift, and Margot Feuer, the “Mothers of the Mountains,” used the momentum to bring the crusade to create a Santa Monica Mountains National Park back to Washington.

Nelson, who lived in Mandeville Canyon, an area that would have been almost completely obliterated by the Mountain Park development, founded Friends of the Santa Monica Mountains Parks and Seashore. She also set to work documenting some of the key resources of the Santa Monica Mountains—flora, fauna and Native American cultural heritage sites.

Margo Feuer, active in the fight to save the Malibu coast from the county’s high density plans, became a Sierra Club lobbyist. She and Nelson made multiple trips to Washington to advocate for the park plan before Congress.

Jill Swift, a passionate naturalist and hiker, founded the Sierra Club’s Santa Monica Mountains Task Force. She led protests and public hiking events to oppose development and build support for the park.

The three activists and their allies gained the support of representatives Anthony Beilenson (D-Woodland Hills), and Philip Burton (D-San Francisco). Burton, chair of the Interior Subcommittee on Parks, included the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area in his 1978 Parks Omnibus Bill.

Critics mocked the size and cost of the bill, calling it “park barrel.” The SMMNRA was only a small part of the whole package but the proposal still attracted vociferous opposition. It wasn’t enough to get it removed from the bill, but it resulted in significant cuts to the amount of money earmarked for the new park. Even the pro-conservation Carter administration balked at the $180 million price tag for the project. The Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area was signed into law by President Jimmy Carter on November 10, 1978, but with a fraction of the funding needed to acquire more parkland.

The state had already begun adding more beaches, mountains, and canyons to its network of parks in the Santa Monica Mountains. Malibu Creek State Park, which now included 1,000 acres formerly owned by entertainer-turned-real-estate-developer Bob Hope, opened to the public just months before the NRA was approved. Some key smaller pieces, like 63-acre Point Dume State Beach, were added in 1979, but the National Park Service—tasked with overseeing the newly created NRA—still didn’t own a single acre.

The National Park Service acquired Rancho Sierra Vista in Ventura County in 1979. A decade earlier, the state negotiated with the owner, Richard Ely Danielson, Jr., to acquire what is now Point Mugu State Park from him. Danielson’s remaining 883 acres were earmarked for a housing development with hundreds of homes. The land was sold instead to NPS for $6.8 million.

An effort to purchase Paramount Ranch was more complicated. Originally a movie backlot ranch before it passed into private ownership, this 750-acre property was the home of the original Renaissance Pleasure Faire beginning in the 1960s. It was a priority acquisition because of its biodiversity, but it also had cultural and historic significance. That didn’t stop the owner of the property from planning a housing development and shopping center.

This was one of the first major tests of the newly created national recreation area. Paramount Ranch was a priority acquisition, but county officials showed every indication of prioritizing development over conservation. Many observers viewed the fight as a lost cause, but the Agoura Hills activists wouldn’t give up.

The National Park Service finally acquired 336 acres of Paramount Ranch in 1980. It was the first NPS land in the Los Angeles County side of the National Recreation Area, but it was a partial victory. The threat of high density development on the remaining acres remained. There was little money available even for the most critically important property on the priority acquisitions list, and the cost of land was skyrocketing.

Three years after the SMMNRA was created, James Watt, President Ronald Reagan’s newly appointed Secretary of the Interior and a passionate advocate for developers’ rights, declared war on the SMMNRA. Watt was unable to deauthorize the park, but he cut what little federal funding was available. A new strategy was needed for the park to succeed.

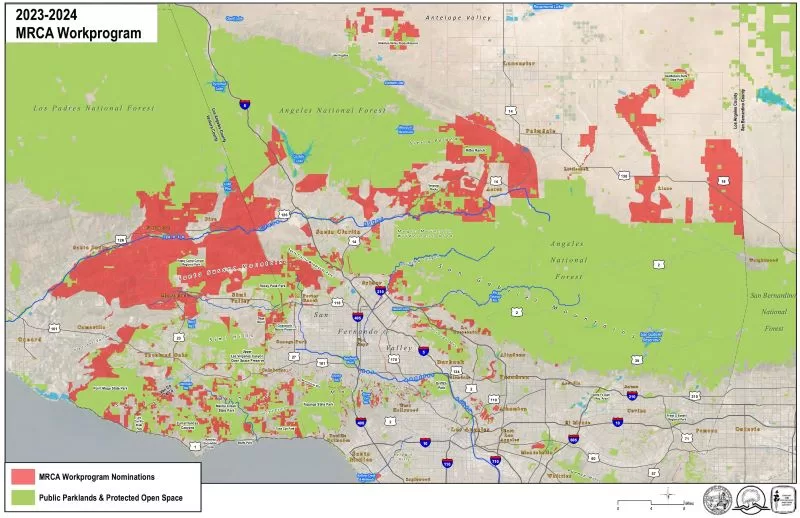

The Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy (SMMC) and the Mountains Restoration and Conservation Authority (MRCA) were created by Governor Jerry Brown in 1979, to enable the state to acquire key sections of parkland the federal government refused to fund. These two sister state agencies rapidly became the new National Recreation Area’s lifeline.

Joe Edmiston, the brilliant, controversial executive director of the two agencies, rapidly proved to be a highly effective negotiator, treating the process of acquiring the missing pieces of the park like a high stakes chess game.

When the owner of the remaining 314 acres of Paramount Ranch was killed in a private plane crash in 1991, and was found to have been in arrears with his bank, Edmiston’s agency swooped in and purchased the delinquent loans.

“It means we can now play Simon Legree to the developer,” Edmiston told the Los Angeles Times in a June 1991 interview. “I’m going to have to get a black silk hat and grow my mustache into a little twirl,” he joked.

The development company, which had already received permission to build condominiums on the site, now had no way to pay for their project. They folded. The conservancy acquired the property for almost $2 million less than they had initially offered the developer.

The SMMC used the same strategy the same year to circumvent a 500-home tract development and a garbage dump in Mandeville Canyon. By purchasing the trust deeds held by the creditors of the bankrupt Eastport development company, the agency was able to acquire 1,518 acres of critical habitat that had seemed just months earlier to be out of reach.

In 1987, the SMMC bought 211 acres in lower Solstice Canyon in Malibu for $2.5 million. The move neatly blocked a development plan for a housing tract at the top of the canyon. A year later, The Trust for Public Lands purchased the rest of the land. This canyon was a top priority acquisition from the beginning and it became the NPS’ first coastal property in the SMMNRA.

In 1990, Nelson, together with a new generation of TASC volunteers, including TASC chair Susan Nissman, and lifelong Topanga activist Rabyn Blake, took on another attack on Topanga: the 275-acre Montevideo development (later known as Canyon Oaks), proposed for the Topanga Summit. This development would have bulldozed the headwaters of Topanga Creek to build a golf course, and luxury country club estates.

Nissman joined TASC shortly after she and her husband, Arthur, moved to Topanga in the late 1970s. Nissman, an artist, grew up in a family that appreciated nature. She and her husband were drawn to Topanga because of its natural beauty. I interviewed her in 2019 for a feature on the Mothers of the Mountains. She told me how she first encountered the Topanga conservation movement.

“There was a table laid out below us in a field and people riding around on horseback,” she said. “They were all there protesting a new subdivision. My husband and I walked up, and boom!”

When the Montevideo development was proposed, Nissman jumped into the fray. She worked extensively with Nelson but also remembers Swift. “Sue had a tough intelligence,” Nissman said. “She never deviated from her core mission to protect the Santa Monica Mountains. She wanted to save it for everyone. Jill was intense. They both had tremendous focus.”

Nissman also worked with Blake. The women forged a strong friendship during the fight to save the Summit. Nissman described it as truly being like a military campaign in the sense that it was one that required grueling hours of strategy, rallying troops to pack dozens of Los Angeles County meetings in downtown LA, and a lot of patience and stamina as the fight ground on for 16 years.

They were aided by other extraordinary women—archeologist Lynn Gamble joined Nelson in Washington DC to give testimony to Congress; Resource Conservation District biologist Rosi Dagit shared her knowledge of mountain ecology; and Topanga Town Council president Marty Brastow rallied the volunteers. The activists knew they were facing a marathon, not a sprint and won in part by wearing down the opposition. In 1994, the development company agreed to transfer the property to the SMMC. Today Summit Valley Edmund D. Edelman Park is named for the Los Angeles County Supervisor who worked with the activists and managed the eleventh-hour play that saved the land.

Within 15 years of its creation, the SMMC, helmed by Edmiston, had acquired 20,000 acres for the NRA. Joe Edmiston has many critics, and the conservancy could not have achieved what it has without the support and determination of grassroots activists and the involvement of state agencies, non profits, local governments and the National Park Service working together, but the SMMC has facilitated what the federal government could not on its own: acquiring more than 72,000 acres of public open space and stitching together a major national park on the edge of one of the most urbanized areas in the country. These two agencies, the one with the power to acquire land, the other with the authority to manage it, have authority that now extends beyond the geographical confines of the Santa Monica Monica to include the rim of mountains that surround the LA Basin.

There have been mistakes, lost opportunities, outright failures, and sometimes unintended consequences, but today the SMMNRA extends from from Point Mugu in Ventura County, along the entire Malibu coast, through the mountains to Topanga and Pacific Palisades, and beyond, reaching as far east as Franklin Canyon above Beverly Hills. It has grown to include parts of the Santa Susana Mountains in the San Fernando Valley, and the Simi Hills.

Activists, nonprofits and government agencies have worked together over the past 45 years to save 5,400-acre Ahmanson Ranch, 2,300-acre Jordan Ranch, and 588-acre King Gillette Ranch, which, at the urging of Margot Feuer, became home to the Santa Monica Mountains Anthony C. Beilenson Interagency Visitor Center.

A plaque at the visitor center features this quote from Feuer about the creation of the National Recreation Area: “The public is so often chastised for not really hanging in to achieve action on a particular cause. This reaffirms the need for really hanging in. All those people who worked—for that length of time—did it.”

Currently, more than half of the Santa Monica Mountains is public open space. If all of the remaining pieces of the quilt in this mountain range are successfully acquired, the final size of the open space portion of the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area will be around 100,000 acres. But even within the 53,250 acres that are developed, there are important ecological resources and habitat in yards, gardens, and along the roadsides. Everyone who lives, works, or plays within the boundaries of the park is invested in this place. We are all stewards and stakeholders.

The SMMNRA continues to evolve. Deer Creek Beach, 1,241 acres, including 2.2 miles of coastline, was added to the SMMNRA just this year, after being on the priority acquisitions list from the very beginning. And there are plans to extend the park designation to the Rim of the Valley that may someday soon more than double the National Recreation Area’s size. The current Rim of the Valley Corridor Preservation Act senate bill, co-authored by California senators Alex Padilla and Dianne Feinstein, was quietly approved in committee earlier this year. It was placed on the Senate Legislative Calendar on July 25, 2023, almost exactly 45 years to the day that Burton’s Park Omnibus Bill arrived on the floor of the senate. The companion house bill, authored by Adam Schiff (D-Burbank) was already approved by the house in an earlier session. It was reintroduced in March of 2023.

Topanga State Park is now at the center of the “Big Wild,” an 18,500-acre open space area that extends from the Pacific Ocean at Topanga State Beach, along Topanga Canyon Blvd. almost as far as the 101 freeway in Woodland Hills, and all the way to the 405 freeway in West Los Angeles. Today, nearly 75 percent of Topanga is protected as part of the SMMNRA, and pieces of the patchwork continue to be added, filling in missing parts of the pattern. The push to create a local National Park began here more than a hundred years ago. Some of Topanga’s most ferocious environmental fights were fought to save it and even now, when this parkland is part of something much bigger, Topanga remains in many ways the heart of the mountains, the rare and special place that made all of this a reality.

I would love to meet you. I am involved with the Santa Monica Mountains Fund and my my mother was Susan Nelson. I live in the mountains near Cold Creek

Thank you, Sara! I would love that, too! You can reach me at suzanne(at)topanganewtimes.com.