Bands played, flags waves, dignitaries gave speeches from a bunting-festooned platform, and hundreds of motorists lined up at Sycamore Cove at the western edge of the Topanga Malibu Sequit Rancho for the grand opening of Theodore Roosevelt Highway. It was June 26, 1929, The long-sought, hard-fought state highway through Malibu was finally a reality, but instead of a well-designed, smooth-flowing corridor for commerce and transportation, the dignitaries were opening a Pandora’s box of problems that continue to plague Pacific Coast Highway (renamed once Teddy was no longer the man of the hour) from the Santa Monica Pier to Point Mugu.They are problems that were baked in from the beginning and continue to plague residents, visitors, and commuters.

May Knight Rindge, the last owner of the Malibu Rancho, spent much of the family’s fortune fighting to keep the highway out. A decade earlier, May successfully blocked Southern Pacific Railroad’s power play for a rail line through Malibu. It took numerous lawsuits and a loophole that said that there was only one railroad right of way. May established her own railroad company in 1905, and forced Southern Pacific to detour around the Santa Mountain Mountains to reach Los Angeles. But by 1915, when she was celebrating her victory over Southern Pacific, rail was already on its way out, eclipsed by the increasingly popular automobile.

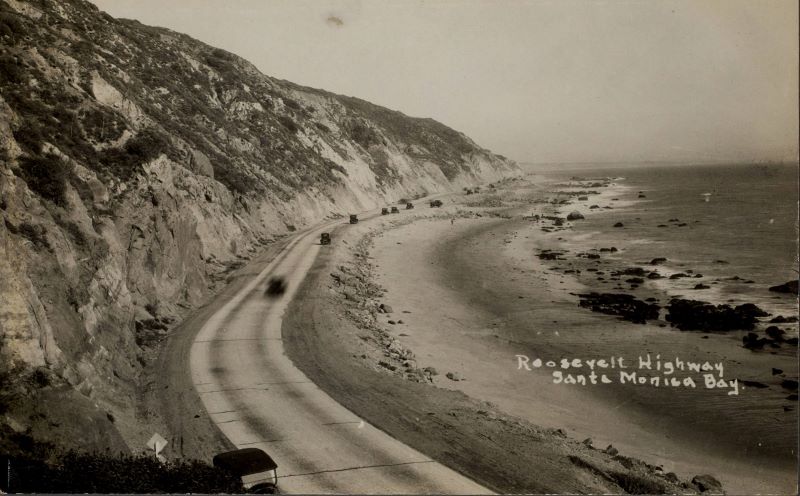

May could not prevent the state and county from bulldozing a highway through her property—the demand for new roads and the power of the newly created automobile lobby was too much even for this indomitable fighter. She lost that battle in front of the Supreme Court in 1926. Road construction began at once. It had already begun on the eastern side of the ranch. This wasn’t construction based on an engineer’s plan, it wasn’t designed to take into account the terrain or geology: it was a bunch of work crews—including teams of convicts—who were supplied with hand tools and mule teams. In some places, steam shovels and explosives were brought in when hand tools weren’t enough, but this stretch of coast highway was built mostly by hand by people who had little experience building a project of this magnitude. Malibu was so remote that it wasn’t practical to transport shifts out for the day. Workers lived in shacks and tent camps, without the benefit of running water or electricity.

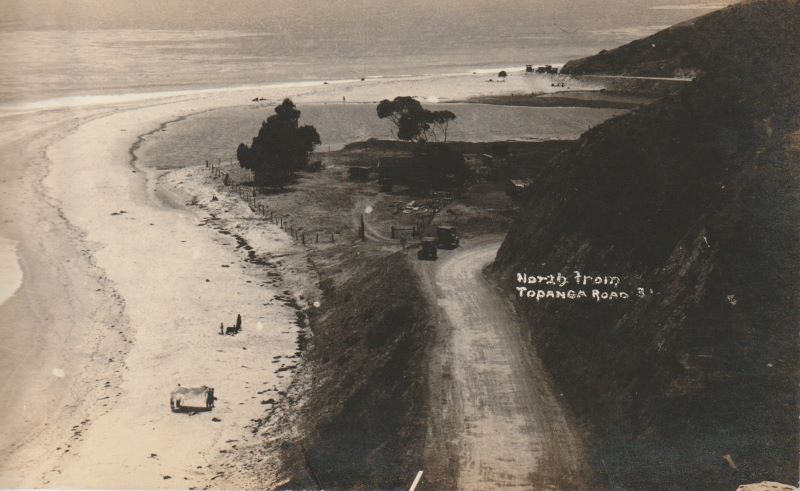

Prior to 1926, the coast route leading up to Malibu was also rough. It meandered along the edge of the beach, ending at Los Flores Canyon, where daytrippers could enjoy sandwiches and ice cream, while travelers bound for further up the coast waited for the tide to turn. The only way through the Malibu Rancho in those days was along the wet sand on the beach. When big surf and high tides coincided that could be a long wait, and a long journey that sometimes involved camping out on the beach and waiting for the next low tide.

Before May Knight Rindge and her husband, Frederick Hastings Rindge, bought the Malibu Rancho in 1892, the route was open to all travelers, although it also attracted cattle rustlers, highwaymen, and other outlaws. Wagons and stagecoaches were sometimes swamped by waves. Passengers had to get out and walk, or help the coach driver dig the wheels out of the wet sand. Traveling the coast route through Malibu took stamina and determination. For the homesteaders who lived in enclaves within the ranch or just outside it, that route was a lifeline, but travel was never easy.

After the Rindges purchased the Malibu Rancho they put up gates and stationed armed ranch hands at them. They also began buying up land on the western boundary of the ranch, closing down coast route access for the homesteaders who lived in the canyons. Those residents had a choice of trespassing or traveling a precarious route down into the Conejo Valley, where a stagecoach connected Camarillo to Calabasas.

Those lucky enough to be invited onto the ranch—or to find the gate open and its guardian absent—had the coast road to themselves. It was an unpaved single-track that crossed more than 27 miles of open land. In some places the road was right on the beach, running parallel to the Rindge railroad tracks; in others it followed along the precipitous edge of the cliffs. May Rindge was an early adopter of the automobile and the road was usually passable, although sections of it washed out in the winter, and obstacles included sheep, cattle, elephant seals, rockslides, and beach sand that could trap the unwary motorist.

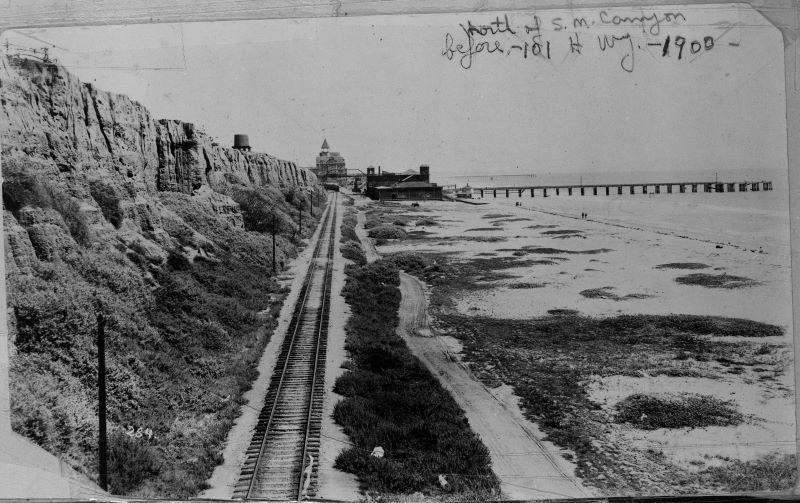

Those were hazards faced by travelers on the road out to Malibu, too, right up until the 1920s, when the coast route was paved and the Rindge Ranch route opened to the public. The earliest image of the Santa Monica coastline the author could find is a stereoscope image from the 1870s. It shows a narrow cart track winding its way north between the beach and the towering cliffs.

A decade later, that wagon trail was replaced by railroad track as part of an unsuccessful plan to turn the Santa Monica Bay into the Port of Los Angeles. Southern Pacific trains ran from Santa Monica, along the coast to the Long Wharf at what is now Will Rogers State Beach. Warehouses, boarding houses, and an entire fishing village of around 500 sprang up around the wharf, but the road north remained a dirt track.

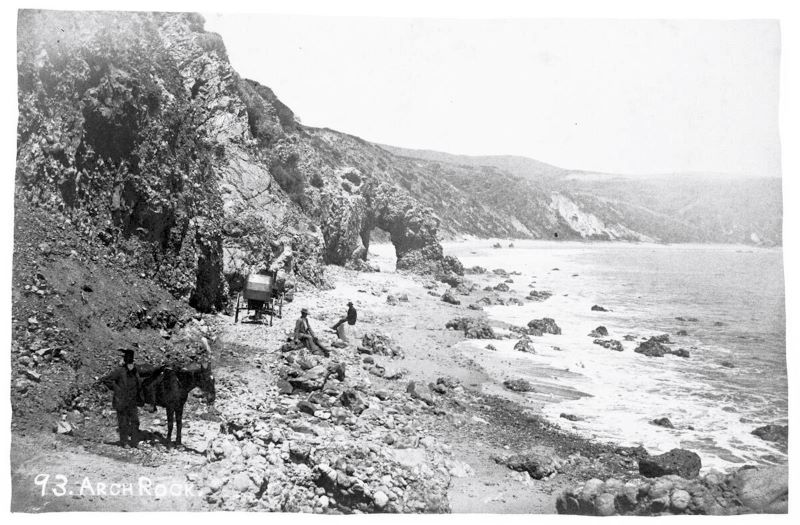

By 1905, Topanga began making headlines as a destination for adventurous motorists. That was the year that Arch Rock, a landmark and tourist attraction located where Maestro’s Ocean Club restaurant is today, mysteriously disappeared during the night of March 24, 1905. Many people blamed an over-eager county road building crew, others accused May Rindge of commissioning the demolition to enable the heavy equipment needed for her railroad project to traverse the narrow route, but the destruction could just as easily have been the result of high tide and big waves. Nothing on this stretch of coastline is as permanent as it seems.

Pioneering filmmaker Thomas Ince built a film studio on 18,000 acres at the mouth of Sunset Canyon in 1911. That brought the first onslaught of commuter traffic to the coast road, and put places like Topanga beach in reach for film crews for the first time, but the road remained a narrow track. Accidents and mishaps were frequent. When they involved the new celebrity class of silent film stars they made headlines. For several years, the coast route ran right through an elaborate Scottish village set built for the 1916 film Peggy, starring Broadway star Billie Burke. The church set endured long after the rest of the studio buildings burned in a wildfire. It remained a roadside landmark until 1933.

When the Supreme Court cleared the way for the coast route across the Malibu Rancho in 1926, county crews were ready to start work, but in the rush to complete the road the builders made mistakes: carving the route through numerous earthquake faults, landslides, and unstable bluffs; filling in creeks, canyons and wetland areas; and building too close to the ocean. This wasn’t a road designed for permanence, it was one hastily slapped together to meet a deadline.

The rock slides at Big Rock that resulted in road closures and traffic delays over the winter of 2023-2024 are just the latest in a series of rockslides in an area that has been geologically active for hundreds of thousands of years. The Malibu Coast Fault is responsible for the dramatic cliffs that line PCH from Santa Monica through Malibu. This thrust fault, which moves vertically, is thought to be more active at its eastern end, where it meets the Santa Monica Fault, but all along the upper plate of the Malibu Coast Fault, the steep natural slopes are made from large old bedrock landslides or from bedrock that has been weakened by tectonic shearing and fracturing. The exposed surfaces are further weakened by weathering. Malibu’s numerous landslides are prehistoric and tend to be slow-moving but they are still active. Pour enough rain on them during a wet winter and they rumble back to life. Cut the toe out from the bottom of an old debris flow to make room for the road, and dirt and rocks are almost guaranteed to fall the next time it rains.

In April 1979, a rockslide on the same stretch of PCH at Big Rock shut the road down for more than a month. Two days after the road officially reopened on May 7, a new slide closed the road again. The road remained closed for months. A water taxi ferried commuters and visitors from the Malibu Pier to the Santa Monica Pier for the duration.

In 1995, severe winter storms once again shut down PCH near Big Rock. The same series of storms also damaged the Malibu Creek Bridge. State transportation officials asked drivers to “avoid Pacific Coast Highway for several months,” while the bridge was repaired and the landslides stabilized. Residents were escorted by sheriff’s department squad cars through a single muddy lane on PCH while crews worked 24 hours a day to clear the road.

In February of 2005 a slide at Big Rock once again closed PCH in both directions for days, and there have been many smaller slides. The most recent closures were not a surprise for longtime residents and commuters, but that didn’t make the situation any easier.

The slide currently blocking the right lane just west of Sunset is another example of an ancient active landslide that was reactivated by heavy rains. News accounts record numerous similar events. One of the most famous slides occurred on February 11, 1956, when a 275-foot-high cliff in Pacific Palisades collapsed onto a 600-foot-long section of the highway, carrying portions of houses and gardens onto the road and shutting the highway for nearly a week, but less spectacular slides are also dangerous and inconvenient, like the series of three slides in in April of 1978, just north of Chautauqua Boulevard that shut traffic down for days while crews struggled to stabilize rain-saturated hillsides, or the one in June of 1998, that shut down the highway between Las Flores Canyon and Topanga Canyon.

Slide zones are present almost everywhere the road runs beneath the cliffs. Landslide remediation measures have ranged from dynamite to complex barriers of steel and concrete, and steel mesh nets, but a permanent solution that doesn’t involve reengineering the entire landscape remains elusive.

Caltrans also continues to grapple with coastal erosion at pinch points like Las Tunas Beach and Thornhill Broome Beach. In both locations the state has prioritized protecting Pacific Coast Highway, using hundreds of tons of rocks to armor the road. At Thornhill Broome, that effort—first undertaken in 2018—had to be repeated this winter, when the rocks used to protect the eroding road were swept away again. Another big storm like the ones we had this year will inevitably cause the cycle to repeat.

Other parts of the Pacific Coast Highway face similar problems. Up in Big Sur, a 1.5-mile stretch of the highway remains closed to the public due to rock slides. Access is for residents only, and requires police escort along one lane, with a lengthy wait. A recent feature in the New Yorker questions whether that stretch of PCH should—or even can—be repaired.

At Gleason Beach in Sonoma County, where erosion has caused several cliffside homes to collapse onto the beach and put the coast route at risk, officials have been forced to develop a plan to move an entire section of PCH inland.

For much of the Santa Monica and Malibu areas, where the highway is sandwiched between steep cliffs and the high tide line, relocation isn’t an option. The houses that line the ocean side of the highway may be some of the most valuable real estate in the country but they are also some of the most vulnerable to rising sea level.

Just because one can build a road doesn’t mean one should, or that it will last forever—especially in a dynamic, constantly changing environment like the coastal edge of a continent, a landscape that continues to be shaped by tectonics and erosion. May Rindge lost her battle to keep Pacific Coast Highway out of Malibu, but she may still have the last laugh.