I’ve made a bit of an effort lately to keep my eye out for new, more diverse reading material and the exercise has paid off.

Sometimes the “recommendation” comes from seeing a familiar title or author that seems to pop up with regularity in the grid of a New York Times Crossword puzzle prompting the realization that a whole lot of people out there know this one and maybe I should too.

A similar feint of ignorance embraces me when I am enjoying one book that alludes to another and the author goes to no effort to explain the correlation beyond the implicit assumption that the reader should have arisen to a degree of cultural literacy that no explanation is necessary; that by simply invoking the name of an author or the title of another book, no more need be said as to its meaning.

At other times, when people learn that I write a lot about books, I’ll be asked if I have read this one or that one and, while not quite embarrassed to admit that I know nothing of it, I do feel a bit of a void followed by the nag to fill it. This is especially true when the book is recommended by the thoughtful, often-introverted type who has already shown that they view the world with curious eyes and ears… like readers of this column, for instance.

Anyway, it has happened enough times for me recently that I have now got myself in the habit of reading books that previously would not have made their way to my shelf. In just about every instance, this exercise in open-mindedness—if I may call it that—has not only yielded a bountiful crop of literary gems, it seems also to have boosted my crossword skills.

Most recently, I have been drawn to two books that were written many decades ago: The Big Rock Candy Mountain (1943) by Wallace Stegner and Revolutionary Road (1961) by Richard Yates. Stegner’s name rang familiar as some of his non-fiction work on the environment of the West was part of my master’s program. Yates was not familiar at all but came to me after my mother’s recently downsized life left me flush with all manner of reading material.

After looking into it, I was stunned with how popular each of these masterful authors was in their day. It is also telling that these two volumes and many more by both Stegner and Yates are still available today.

The Big Rock Candy Mountain follows Bo Mason and his family from the turn of the twentieth century into the 1930s in and around the Northwest United States and Saskatchewan. Bo’s wife Elsa wants nothing more than to settle down long enough to call a place home; while Bo uproots his family repeatedly in search of, well, The Big Rock Candy Mountain where he can “make a pile.” Unfortunately, the land of “lemonade springs where the bluebird sings” can’t be found on any map.

In Revolutionary Road, Frank and April Wheeler are also in search of the American Dream, this time in 1950s suburbia. And, while this one can be found on maps all over the country, the reality is that the American Dream, for many, is about as elusive as Bo Mason’s mountain.

Richard Yates’ fluid prose destroys the myths surrounding post-World War II suburban life while crafting characters oddly aware that they were playing some social game where the first rule was to uphold the lie; live the myth long enough and it just might come true. If this sounds familiar, you shouldn’t be surprised, for we live in an age bombarded with the photo-shopped versions of each others’ lives so often standing in for the real thing. This is a great and relevant novel. (Thanks, Mom.)

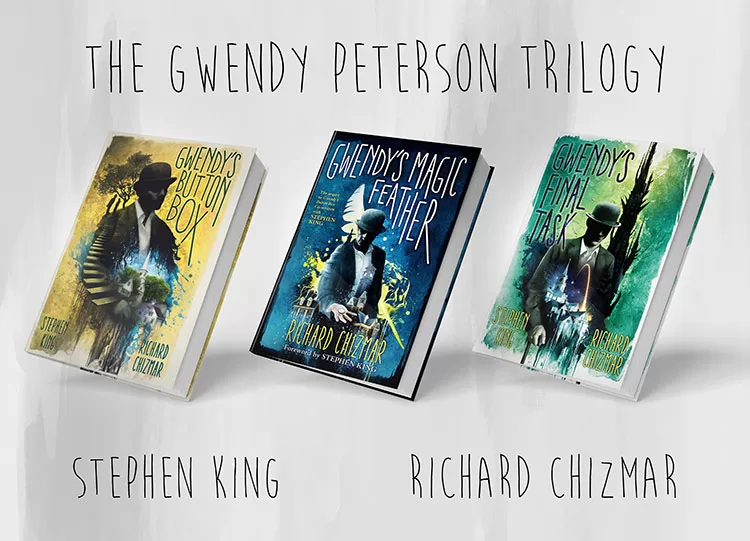

My recent interest in Stephen King drew me to a trilogy of books by King and Richard Chizmar which follow Gwendolyn Peterson through three distinct stages of her life.

When a mysterious man entrusts Gwendy with a precious button box in Gwendy’s Button Box (2017) the awkward pre-teen finds herself burdened with a great responsibility. Each of the colored buttons on the box represents a continent and pressing one will make strange things happen there; exactly what will occur is somehow dependent upon what is on the mind of the button-pusher. Besides the buttons, there is a lever on either side. One offers up a tiny chocolate treat in the shape of an animal when pulled. Not only is the treat the best kind of sweet, it has a rather interesting pharmaceutical quality. Oddly, another lever delivers an 1891 Morgan Silver Dollar, just about every time it is pulled. Curiosity, temptation, greed, addiction, retribution, and only a bit of terror are but a few of the emotional tugs that seem to follow whoever possesses the box. And, of course, with Stephen King at the helm, a few bodies show up, too, although the horror in this one derives mainly from the internal dilemma of possessing so much power.

In Gwendy’s Magic Feather (2020), written exclusively by Richard Chizmar, our heroine is middle-aged. Then, in Gwendy’s Final Task (2022), where we begin to understand the true nature of the button box, she has reached her sixties.

The origin of this story idea and the subsequent collaboration of King and Chizmar are interesting, as well; providing insight into how one of the most prolific writers of our time operates. And if that intrigues you, I suggest King’s On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft (2000).

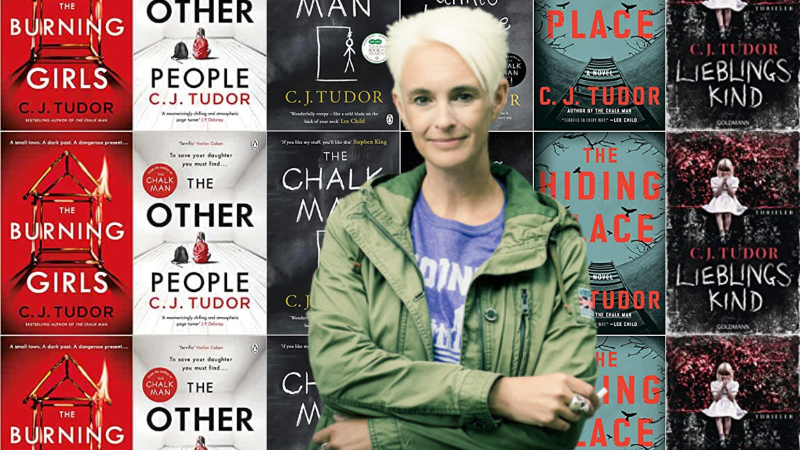

I discovered another new writer this year simply by perusing the stacks at my library. Novelist C.J. Tudor has published a book a year since her debut in 2018, The Chalk Man. Most of her stories are set largely in and around the small villages of the English countryside. Tudor’s mysteries are tinged with a hint of the supernatural tendencies of a Stephen King but tend to close with explanations that might actually be of this world. On one book jacket, Stephen King writes, “If you like my stuff, you’ll like this.”

Other C.J. Tudor books include The Hiding Place (2019), The Other People (2020), The Burning Girls (2021), A Sliver of Darkness: Stories (2022), and The Drift (2023). The common thread is Tudor’s vivid imagination.

As a teenager in 1986, Eddie spends time getting into trouble with his motley band of friends who communicate with one another by drawing chalk symbols around town. Thirty years later in 2016, chalk figures begin to show up and the dirty deeds of their youth catch up with them.

In The Hiding Place a down and out teacher returns to his boyhood home and rents a house that has been the site of a gruesome murder because the price was right.

The Other People takes us into the Dark Web and to a site where sinister favors are exchanged. For example, if you were seeking revenge against someone who had done you harm, this clandestine island in uncharted cyberspace can hook you up with someone seeking similar revenge against someone else. You each take care of the other’s problem while creating alibis for each other. Tudor’s twists on this very real Internet threat had me paging back and forth just to make sense of who did what; great terrible fun.

In The Burning Girls, an old village church and a graveyard are haunted by a number of troubling events in a story the publisher describes as an “explosive and unsettling thriller.”

In The Drift, we follow three parallel stories in a post-apocalyptic world decimated by a virus. I was absolutely floored when these three lines finally converged.

It is telling that in the Acknowledgements for The Hiding Place, Tudor writes, “Blimey – a second book. Not so long ago, I had pretty much given up hope of ever having a book published and now here we are: Book 2.” I’m glad she stuck with it because even as The Chalk Man was received with wide acclaim, each of the following stories serves as mounting evidence of a writer coming into her own; and I don’t expect this personal literary evolution to slow down any time soon.

I have one more book to share and I saved it for last due to my hesitation to violate the holiday commandment to avoid discussions of politics; although my view is that we don’t talk enough. I’ve read many of the Trump Era books that elaborate on what most of us already understand about the 45th president. However, if you want to take a deep dive into what has evolved over the past 30 years or so in our country, and see how Trump came to be, I urge you to read Homegrown: Timothy McVeigh and the Rise of Right-Wing Extremism (2023) by Jeffrey Toobin. (Thanks again, Mom.)

This is not just another insider take. Rather, it is a heavily researched account connecting viscerally the domestic terror of the 1990s—most specifically the Oklahoma City bombing of 1995 that took 168 lives—with the insurrection at the Capitol on January 6, 2021. Toobin supports his arguments with “nearly a million previously unreleased tapes, photographs, and documents, including detailed communications between McVeigh and his lawyers…” This unprecedented access to apparently attorney-client privileged information offers a deep dive into Timothy McVeigh’s efforts to arouse an army of like-minded “patriots” who saw the disasters at Waco, Texas and Ruby Ridge as hard evidence that the federal government was out of control and the time for revolution was at hand.

Toobin also interviewed former President Bill Clinton and current Attorney General Merrick Garland, who played a significant Justice Department role in the investigation and prosecution of Timothy McVeigh.

In the end, McVeigh failed to arouse his army but Toobin makes clear that they were there. He argues presciently that the only thing missing then was the tool of organization; a tool that now exists today as an unprecedented and profound presence in our lives. And, despite a number of wild conspiracy theories floating around now, it might be wise to consider that even the most bizarre of them are often grounded in at least a kernel of truth.

In this one, Donald Trump is not so much an instigator as he is a symptom of deeper discontent within his tens of millions of followers. Toobin makes it clear that we must understand this discontent if we hope to move forward together.

Finally, as I have committed to exploring books outside my initial comfort zone, I continue to welcome your recommendations. Peace to all of you.