The Story of the Adamson House, Malibu, California

Rhoda Agatha Rindge Adamson lived life on her own terms in a time when women—even wealthy ones— rarely had the opportunity to determine their own fate. Her story is eclipsed by the shadow of her more famous mother, May Knight Rindge, legendary owner of the Topanga Malibu Sequit Rancho, but it’s equally remarkable.

Rhoda was the youngest of the three Rindge children. She was just ten years old when her father, Frederick Hastings Rindge, died. Rindge inherited a fortune from his father, Samuel Baker Rindge, a successful Boston merchant. He moved west to California for his health, and purchased the entire 13,5000- acre Malibu Rancho in 1992. He was one of the wealthiest men in Los Angeles at the time of his death in 1903, with interests in utilities, insurance and real estate. The Rindge estate was valued between four and twenty-million dollars, a vast fortune. May Rindge was given the controlling share of the estate, but Rhoda inherited an equal share with her brothers, and that was enough to make all three extremely wealthy.

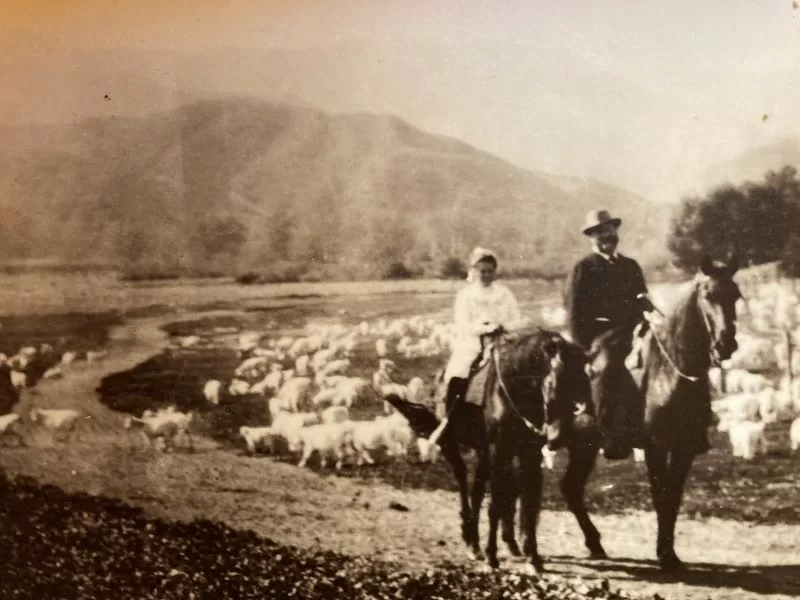

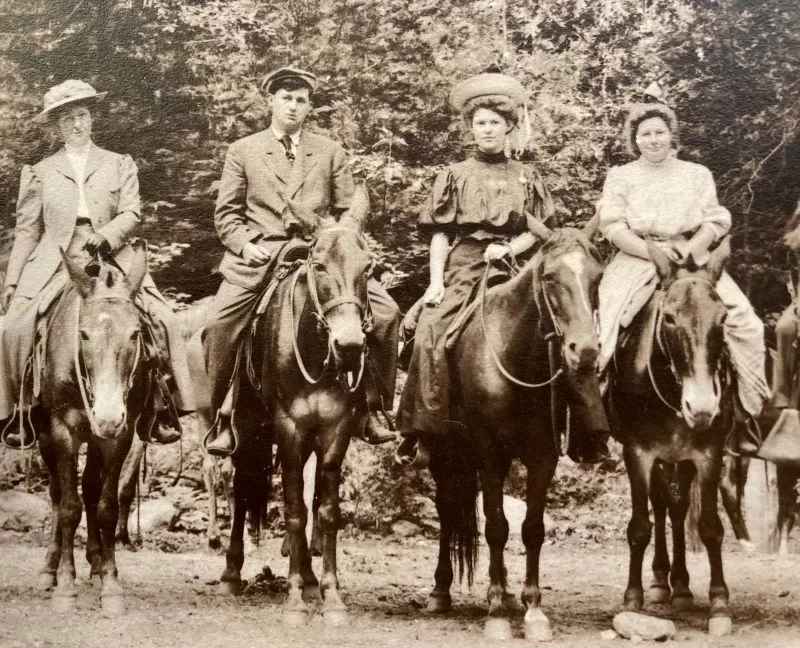

As a child, Rhoda loved reading and spending time outdoors with her animals. As she grew older, she came to love racing: horses, sailboats, and even automobiles—activities young ladies of good breeding were simply not supposed to participate in. Rhoda could ride and shoot as well as any of the cowhands on the ranch, and she could handle a race car with finesse. She liked murder mysteries and historical novels. She preferred the company of her books and animals to society but dutifully attended cotillions and balls, and she soon found herself to be a highly sought after prize in the marriage market.

Both of Rhoda’s brothers made what were considered to be brilliant society matches. When Rhoda’s brother Frederick married Miss Galetta Mushet in 1911, details of the wedding were spread all over the society pages of the major newspapers. When her brother Samuel married Miss Agnes Hole the same year, the LA Times society column artist drew the event in lavish detail. There were 800 guests in a garden decorated with more than 10,000 Cecile Brunner roses. Rhoda, still a young girl, was part of both wedding parties, but somehow managed to avoid having her portrait in the papers with the other bridesmaids. It is easy to imagine her riding her horse instead, or off in a quiet corner with her nose in a good book.

A wealthy heiress was expected to marry to advantage in society, but instead of pursuing a husband, Rhoda went east to college. She spent a year at Wellesley, but was too homesick to stay and finish her degree.

Rhoda faced steep opposition from her mother when she announced she was going to marry Merritt Huntley Adamson, the manager of the Malibu Rancho. She was 22, he was 27. He was a capable ranch foreman and he was a USC graduate—he had been one of the first football stars of the newly formed Trojan team—but as far as May was concerned, he was not the kind of match she had in mind for her daughter.

Rhoda refused to be dissuaded. She enlisted the aid of her brother Frederick and his wife Galetta, and eloped. The wedding ceremony, on November 17, 1915, was a modest affair compared to the weddings of Rhoda’s brothers—just Rhoda and Merritt, Fred and Galetta, and a few close friends at the chapel of the Mission Inn in Riverside. May didn’t attend.

Rhoda and Merritt started their married life by going into business together. They founded Adohr Milk Farms, AKA Adohr Farms or Adhor Dairy, in 1916. The name is “Rhoda” spelled backwards.

The business provided a comfortable living even during the most trying years of the depression. By 1942, Adohr had the biggest herd of Guernsey milk cows anywhere—3000 of them, and a thriving business that included a fleet of trucks and milkmen. Milk and other dairy products were delivered daily to homes all over the Southland by Adhor milkmen who drove special vans.

May Rindge eventually reconciled herself to her daughter’s marriage. She gave the land at Vaquero point—now Surfrider Beach—to her daughter and son-in-law for a beach house. The Adamson House was completed in 1929. It was designed by architect Stiles O. Clements in a fantasy Spanish Colonial revival style and lavishly decorated throughout with custom art tile made by the Malibu Potteries company, owned by May Rindge.

The Adamson House has 10 rooms, a salt-water pool complete with pool house, and acres of gardens on the edge of the Malibu Lagoon, but it was a modest home compared to the mansions of some of the Adamsons’ contemporaries. May herself was building a much grander palace on the hill above Vaquero Point when she was forced to file for bankruptcy in the 1930s. It would have had more than twenty-five rooms, including a suite with an indoor swimming pool.

The Adamsons’ Malibu house was mostly used on weekends and as a summer retreat. Rhoda and Merritt’s children, Rhoda May, Merritt, Jr., and Sylvia, remembered a fairly idyllic childhood in Malibu that included many pet animals. One was a sheep named Bohunkus who walked on a leash like a dog and was as beloved a pet as any other ranch dogs and ponies. They were, however, expected to do chores and to help with the family business. Rhoda May’s first involvement in Adohr Farms came early. She was the first Adhor-able baby—a successful marketing campaign that ran for decades and featured the children of Adohr customers.

In 1937 the Adamsons moved to Malibu full time. May died in 1941, her mansion on the hill above the Adamson house was never completed. It was sold the following year to a religious order, and became the Serra Retreat.

Life at the Adamson House in the war years was quiet and anxious. The Adamson’s three children were grown, Merritt, Sr. was occupied with the impact of the war on the dairy industry. Rhoda quietly dropped out of the news in the war years, mentioned only as Merritt’s partner in Adohr Farms.

There is no record that the Adamsons ever took part in their neighbors’ parties and the frenetic pre-war activities that included tennis and that mad new craze imported from Hawaii—surfing. Frenetic activity of a different sort replaced the pre-war diversions.

War fears, fueled by reports of enemy submarines off the coast, transformed Malibu into a ghost town by the spring of 1942. Everyone was convinced that an attack was imminent.

Property values dropped as the military rolled in. Anti-aircraft guns were installed along the coast, including above the Malibu Pier. When the guns were tested for the first time no one thought to warn the residents, who were terrified and convinced Malibu was under attack. After that, warnings were usually issued in advance, but drills continued to rattle nerves.

For Rhoda and Merritt Adamson the decision to stay at their beachside home on its isolated point of land must have taken both courage and stubborn determination.

The Civil Defense, charged with preparing a 300-square-mile section of the Santa Monica Mountains, from Malibu to Topanga and from Yerba Buena to Calabasas, where busy organizing volunteer wardens, Red Cross casualty stations, patrols, fire wardens, and transportation, housing and entertainment for the troops stationed in the area. A huge air raid siren described by the Malibu Bugle newspaper as a “bearcat” was installed on the county courthouse at La Costa in the spring of 1942. Smaller sirens were placed on telephone poles or even atop cars.

The Coast Guard was charged with patrolling the entire coast. They commandeered the Malibu Pier and wanted the Adamson House, too, but had to settle for the pool house instead. It became home for the officers, while the enlisted men were bivouacked in tents behind the house.

The Adamsons became familiar with the routines of the Malibu beach patrol. Each team consisted of two men and a dog. The dogs were a mixed blessing. There weren’t enough service trained dogs available, so the military drafted people’s pets. At least their presence provided company for the patrollers. It was a lonely business, especially on a stretch of coast like Malibu, where there were few houses and fewer people..

The war brought other changes. The Adamsons leased land to a Japanese American family, the Takahashis, who grew strawberries, truck crops like spinach, and geranium flowers. The government incarcerated them in Manzanar in April of 1942.

When the Civil Defense did finally have a battle on their hands the following year, it was a wildfire not an invasion. Fighting this fire was a challenge. Almost all of the able-bodied men had been drafted. The fire fighting force was made up of inexperienced volunteers. Just a few years earlier it would have been unthinkable for women to serve as firefighters. That changed during the war.

The Adamson House was spared from the 1943 Woodland Hills fire, which burned a wide swath of the Santa Monica Mountains—14,000 acres—but the Adamsons had other worries. Rationing and government price-setting were a hard burden and war shortages were a problem.

Sugar was the first item to require ration coupons beginning in May 0f 1942. It was the last to be restored to the open market in 1947. Fresh milk wasn’t rationed, but butter and cheese were, and milk went into many products that were suddenly not readily available, like the ice cream the Adamsons donated every year for Judge Webster’s Christmas party for the community’s children.

By 1943, the ration list included meat, butter, coffee, shoes, canned goods—including canned milk. Gas, oil, tires, automobiles and car parts were among the first products to become scarce. Tire and gasoline rationing followed sugar rationing in the summer of 1942. It impacted every aspect of dairy production and delivery. The friendly neighborhood Adohr milkman could no longer deliver daily. The government would not allocate more gas for delivery trucks and tires were simply not available, neither were parts for farm equipment like the combines used to harvest alfalfa out at the Adohr Farms fields in Palmdale that provided feed for the cows kept at the dairy feedlots in the San Fernando Valley.

Merritt became a key spokesperson for the dairy industry, meeting with government officials and other business leaders in his industry. It took him more often from home, and travel was complicated by the dim-out, instituted in May 1942. Dim-out meant no headlights on or along the coast after dark and that all household lights had to be blacked out so no light showed. Even flashlights were forbidden.

The goal was to reduce the risk of an air strike, but it made travel after dark incredibly dangerous. It was a frightening time for everyone, but the handful of hardy souls who stayed in Malibu lived with the constant fear of invasion.

The war ended on August 15, 1945. Merritt didn’t get to enjoy the postwar prosperity. He died in 1949. He was only 61. Rhoda continued to run the dairy and live in the house they built together until her death in 1962, at 68.

Rhoda’s mother was one of the first and only women to serve as president of a railroad, and she successfully defeated Southern Pacific Railroad, one of the most powerful companies on Earth. Her daughter Rhoda ran Adohr Farms for 20 years after the death of her husband.

At the end of her life, Rhoda turned to the past, living with her memories in her house by the sea, changing almost nothing. In the garden behind the kitchen is a bathtub where Rhoda washed the family pets. Inside the house is the elevator she installed when she could no longer climb the stairs. The shelves are still full of her books. Family photos show her with husband, children, dogs, horses and the family’s pet sheep.

The Adamson House is owned by California State Parks. Visitors to the house and the small museum that is housed in the garage where the family’s Pierce Arrow cars once were kept, experience not only the opportunity to enjoy the extraordinary tiles and arts-and-crafts-era architectural details that fill the house, and the gardens that run down to the edge of the sea, but also get a glimpse into the life of the stubborn, determined, intelligent woman whose home it was.

Learn more at https://www.adamsonhouse.org