This article was originally published February 24, 2023 in Topanga New Times.

In the twenty-first century, Cobalt (Co on the periodic table) has become a highly valued commodity; one of the few elements that make our rechargeable batteries perform as they do. In 2021, 72% of the global supply of cobalt came from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in the heart of sub-Saharan Africa. All indications are that our dependency on Congo cobalt will continue to grow, as roughly half of the world’s known reserves are found in a small area in the southern region of that horribly misnamed country.

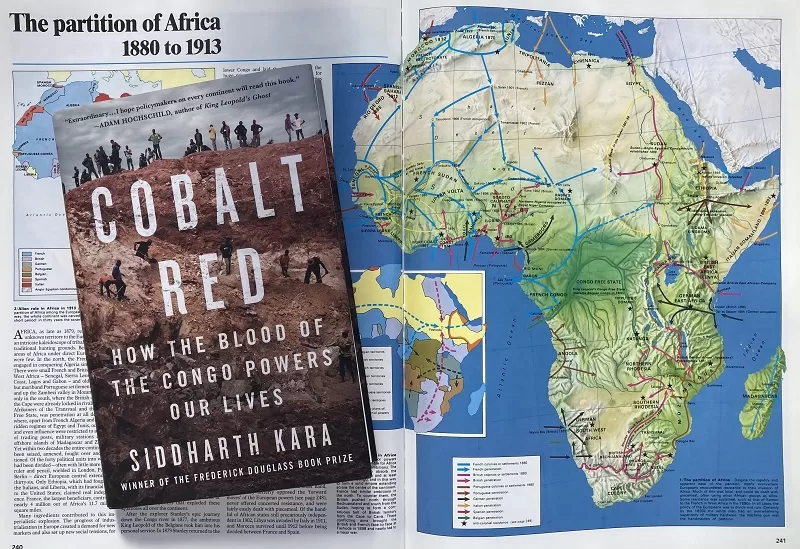

As Siddarth Kara observes in Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives (2023), the mining of cobalt ore has become a critical part of the “rechargeable battery revolution” infrastructure in which consumers like you and me at the very top of the electric vehicle and device supply chain are bathing in unprecedented technological comfort and convenience; while the bottom of that supply chain is characterized by “slavery, child labor, forced labor, debt bondage, human trafficking, hazardous and toxic working conditions, pathetic wages, injury and death, and incalculable environmental harm.”

Kara makes this scathing and sweeping indictment on page 17. Only a few chapters in, it becomes clear that his argument rests on solid ground; ground that he himself has very recently traversed.

Due to its unique geology, including its proximity to the Great Rift Valley, massive deposits of cobalt ore in the DRC are found just under the surface. Individuals armed only with primitive tools can easily reach veins of cobalt ore. “Artisanal” mining – a euphemism for digging, crushing, and washing cobalt ore with human hands using old pieces of rebar and rusty hand tools – is responsible for up to half of the DRC’s production of cobalt. These laborers earn maybe a dollar or two a day under deplorable conditions and often have very little to eat.

At the heart of Cobalt Red are the heartbreaking stories of a peaceful people subjected to the “foreign mining companies [that] expropriated large swaths of land, displaced villagers, contaminated the environment, offered little to no support to the local population, and left them to eke out a meager existence in dangerous conditions as artisanal miners on the land they once lived on.”

Kara suggests searching “Kolwezi” in Google Earth to see from space what cobalt mining has done to the planet. Lush green vegetation has given way to massive strip mines. Villagers removed from their land now live near the mining operations. The people he encountered and the homes they lived in —layers of dust. The color of the dust was determined by the various ores that held the cobalt from one mine to the next—yellowish in one village, red or orange in another. Lakes and streams are clouded with hues similar to the dust.

Throughout his trips in the mining region of the DRC, Kara, time and again, came across vast expanses of despoiled earth where, in a lone example, thousands of “women, children, and men shoveled, scraped, and scrounged across the artisanal mining zone under a ferocious sun and a haze of dust. With each hack at the earth, a puff of dirt floated up like a specter into the lungs of the diggers.”

In another, “More than fifteen thousand men and teenage boys were hammering, shoveling, and shouting inside the crater, with scarcely room to move or breathe. None of the workers wore an inch of protective gear—just shorts, trousers, flip-flops and maybe some shirts.” And the product of their labors: “At least five thousand sacks of hand dug [cobalt ore] were stacked at the edge of the excavation area.”

In this lawless society, the women and children suffer the most. In one mine, Kara writes, ‘It seemed as if half the teenage girls at the site had infants strapped to their backs.” Many of these children are most certainly the result of sexual assault and rape. “Boys as young as six,” he witnessed, “took wide stances and summoned all the strength in their bony arms to hack at the earth with rusted spades.” This, he adds, is “the invisible, brutalized backbone of the global cobalt supply chain.”

Nearly everyone Kara encountered in his trek was covered with cuts and rashes; and they coughed while speaking to him. Many were unable to work because their bodies had been destroyed in mining accidents, if that’s what we can call them; crushed limbs, infected wounds and, in one area, limbs severed for failing to meet a cobalt ore quota set in place and enforced by armed militias. Untold numbers have died in collapsed tunnels which became their graves.

The militias are hired by those a few notches up the supply chain whose job is to isolate the artisanal miners from Western eyes. In most cases, Kara was given only minimal access to these people and the mines in which they worked. As an Indian, the intrepid author did the best he could to blend into a community where Indian people are not totally uncommon. While using a variety of deceptions to gain access to their stories, artisanal miners speaking to Kara were risking their lives. If someone “speaks to someone like you,” one of his guides informed him, “they will be shot in the night, and their body will be left on the street to instruct anyone else the consequences of opening their mouths.”

This is the dark secret of the very bottom of multi-trillion dollar technology-driven supply chains. At the top are technology companies inspiring a green revolution while proudly claiming that their supply chains are free of abuse.

A critical aspect of this hidden part of the supply chain is that artisanal miners can sell their sacks of ore only to negociants; the equally exploited, but better off, middlemen who deliver the sacks into the larger, somehow-more-morally defensible supply chain. The difference between the artisanal miners and the negociants seems to be access to a motor bike or even a bicycle with which to transport cobalt ore to depots. This is where we begin to see the employees of the foreign mining companies; the majority appears to be Chinese, which makes sense because, “In 2021,” as Kara explains, “China produced 75% of the world’s refined cobalt.”

The artisanal miners are exploited by foreign mining companies who have paid billions of dollars to corrupt Congolese politicians who enrich themselves while looking the other way. Of course, the whole purpose of Kara’s book is to bring attention to the abuses being committed on our behalf. Kara adds, “no one up the chain considers themselves responsible for the artisanal miners, even though they all profit from them.”

When Kara asked a buyer at one of the depots if the ore he was buying came from child labor or is associated with other types of abuse, the businessman replied, “One does not ask such questions here.”

The Congo—as we in the West now refer to this vastly diverse region—has been exploited by foreign powers for a long time, cursed with the wealth of its natural resources, including the commoditizing of its humanity; aka slavery. The Congo was one of the last places to be colonized by European powers; in this case, Belgium. By the end of the nineteenth century, the plunder began; “ivory for piano keys, crucifixes, false teeth, and carvings (1880s), rubber for car and bicycle tires (1890s), palm oil for soap (1900s), copper, tin, zinc, silver, and nickel for industrialization (1910+), diamonds and gold for riches (always), uranium for nuclear bombs (1945), tantalum and tungsten for microprocessors (2000s+), and [now] cobalt for rechargeable batteries (2012+).”

Kara’s statistical evidence is illuminating while his anecdotal observations are intimately profound. Case in point: The Belgian contribution to the Allied war effort in two world wars included providing raw materials used to produce much of the munitions used to defeat fascism. A single mining operation in the DRC provided critical material to manufacture the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.”

“At no point in their history,” Kara adds, “have the Congolese people benefitted in any meaningful way from the monetization of their country’s resources. Rather, they have often served as a slave labor force at minimum cost and maximum suffering.” As Kara laments, “So much time has passed; so little has changed.”

In all measures of life quality, the DRC ranks near the bottom; poverty, infant mortality, access to health care and education. Nearly three-fourths of the population does not have access to clean drinking water. Nine out of ten Congolese have no access to electricity. “It is a system,” Kara injects, “of absolute exploitation for absolute profit.”

Since the vast majority of cobalt in use today has come from the DRC, it is very likely that just about every single one of us has benefitted from the tragic circumstances that continue to plague uncountable thousands of human beings. Kara believes that making us aware of these circumstances will serve to ameliorate these conditions. I am not sure how, but awareness seems a good first step.

It is clear that Siddarth Kara hopes that readers will consider our culpability in this human tragedy and face the fact that “the rechargeable battery revolution has unleashed a malevolent force upon the Congo that tramples all in its path in a merciless hunt for cobalt.” These are certainly guilt-inducing words but they come from his heart and derive from his own reaction upon returning home:

“Nothing looks the same after a trip to the Congo. The world back home no longer makes sense. It is difficult to reconcile how it even inhabits the same planet. Neatly arranged mountains of vegetables at grocery stores seem vulgar. Bright lights and flushing toilets seem like sorcery. Clean air and water feel like a crime. The markets of wealth and consumption appear violent. Most of it was built, after all, on violence, neatly tucked away in history books that tend to sanitize the truth.”

In a world that seems increasingly incapable of reconciling with the horrors of its own distant past, I wonder if we even possess the capability to reckon with the horrors of the present. For my own part, I am a clear beneficiary of the economic injustice inherent within our brutally capitalist system. In the current case, I own devices that contain cobalt that was very likely scraped out of the earth by impoverished black hands. I am not sure what to do about it so the only thing I can say in my defense is that I have begun to think about it, read about it, and share what I have discovered with others. If you are so inclined, perhaps you can do the same.