[Surfing] is one of the most perfect physical pleasures that I have known. —Agatha Christie, An Autobiography

In 1922, at the age of 31, British crime novelist Agatha Christie learned to surf. She was not yet the “Queen of Crime,” but her most famous detective, Hercule Poirot, had already been introduced two years earlier in The Mysterious Affair at Styles. Agatha was in the process of publishing her latest book, The Secret Adversary, when her husband Archie Christie—officially Colonel Archibald Christie—was asked to join a 10-month round-the-world trade mission to promote an upcoming exhibition that was intended to be a sort of world’s fair for the nations in the British Commonwealth. Agatha was invited to accompany her husband. It was too good an opportunity to miss for the adventurous couple. They left their two-year-old daughter in the care of Agatha’s sister, and boarded a steamship bound for South Africa.

Surfing arrived in South Africa a decade earlier, in the years before World War I. Muizenberg, with its perfect surf break and warm water, became a center for the sport. A 1918 Cape Peninsula Publicity Association brochure boasts:

“In the Pacific the islanders have made it an art. At the Cape it has become a cult. The wild exhilaration is infectious. [Surfing] steadies the nerves, exercises the muscles and makes the enthusiast clear headed and clear eyed.”

Agatha Christie grew up by the ocean in the south of England and swam frequently almost until the end of her long life. She and her husband Archie were immediately intrigued by surfing, and embraced the sport with enthusiasm. They purchased wooden belly boards and hit the waves, first in South Africa, and then in Hawaii.

Not everyone who witnesses surfing is willing to give it a try. British traveler extraordinaire Isabella Bird described surfing on her visit to Hawaii in 1876. “It really is a most exciting pastime,” she wrote, but she didn’t give it a go.

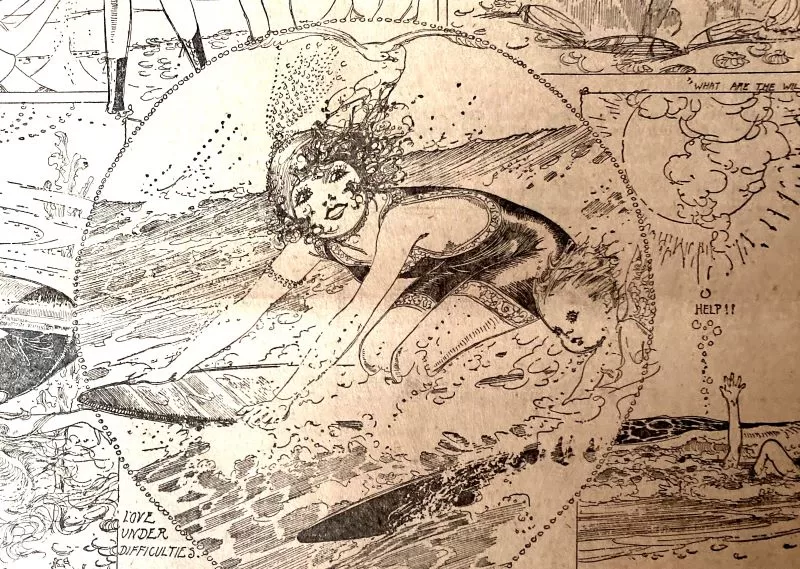

American writer and humorist Mark Twain did try it in 1866, when the fledgling writer was a reporter for the Sacramento Daily Union newspaper. He describes seeing Hawaiian surfers of “both sexes and all ages,” surfing on short wooden boards, and how he was inspired to give it a try.

“I tried surf-bathing once, subsequently,” he wrote. “But made a failure of it. I got the board placed right, and at the right moment, too; but missed the connection myself. The board struck the shore in three-quarters of a second, without any cargo, and I struck the bottom about the same time, with a couple of barrels of water in me.”

Unlike Mark Twain, Agatha Christie was determined to master the art. She described her experiences in her journal and in letters home, which were published posthumously in 2012 as The Grand Tour: Around the World with the Queen of Crime. While Agatha and her husband were staying in Honolulu, she learned to stand up on her board after several punishing wipe-outs, including one that left her half drowned and mostly naked. Her board wasn’t the relatively short, light belly board she used in South Africa, but instead it was: “a great slab of wood, almost too heavy to lift.”

Agatha kept practicing and persevered. “The first six times I came to grief,” she wrote. “Oh, the moment of complete triumph on the day that I kept my balance and came right into shore standing upright on my board!…It was heaven! Nothing like that rushing through the water at what seems to you the speed of about two hundred miles an hour…”

By the time the Christies resumed their travels, they had both become proficient surfers. “All our days were spent on the beach and surfing,” Agatha wrote. “Little by little we learned to become expert, or at any rate expert from a European point of view.”

Agatha brought a board with her back to Britain, and is thought to be one of the first women to surf there, but she wasn’t alone—surfing was gaining popularity at surf breaks around the world.

The first woman to surf in Great Britain may have been Hawaiian Crown Princess Ka’iulani, who was sent to school there in the 1890s, and who helped bring the Hawaiian art of surfing to the attention of the world.

A few years before Agatha Christie learned to surf in Muizenberg, a woman from Zimbabwe named Heather Price became the first woman to master stand-up wave riding in South Africa, with the help of a pair of American Marines and a wooden longboard they brought from Hawaii.

Surfing arrived in mainland America about the same time it reached South Africa. Princess Ka’iulani’s three cousins, Kawananakoa, Kuhio and Keliʻiahonui, demonstrated surfing in California in the early 1890s, but it didn’t really catch on in Southern California until the arrival of Hawaiian George Freeth in 1907.

The story goes that industrialist Henry Huntington saw Freeth give a surfing demonstration in Hawaii. He invited Freeth to come to the newly developed seaside resort town of Redondo Beach, where Freeth gave performances as “The Man Who Walks on Water,” and “The “Hawaiian Wonder.” Freeth introduced Southern California to the art of wave riding, and also pioneered life saving techniques still used by lifeguards all over the world to make sure would-be surfers and other swimmers were safe in the water. He also taught swimming skills, and unlike most instructors, Freeth coached women as well as men.

In 1912, Freeth was joined in Redondo Beach by Hawaiian championship swimmer Duke Kahanamoku, who was training for the 1912 Summer Olympics in Stockholm, Sweden, where he would win a gold medal in the 100-meter freestyle, and a silver team medal in the men’s 4×200-meter freestyle relay.

In the wake of his success from his first Olympics, Duke traveled around the world, demonstrating swimming and surfing on the West Coast in California, and also on the East Coast in places like Atlantic City, New Jersey, and Long Island, New York. Like Freeth, he taught swimming and surfing, and he coached women as well as men. In 1914, Duke traveled to Australia, where he inspired 15-year-old Isabel Letham, who became the first known female Australian surfer.

In the late 1920s, Duke Kahanamoku, now a film star as well as a top athlete, was a regular visitor at what is now Surfrider Beach in Malibu. He was friends with actor Ronald Colman—they appeared together in the 1929 film The Rescue—who had one of the first houses in the Malibu Colony, adjacent to what is now Surfrider Beach.

The Malibu surf scene in those early years included actresses Myrna Loy, Joan Crawford, and Clara Bow—Clara and Duke were in the 1927 film Hula together. She was reportedly a powerful ocean swimmer, and she enjoyed the challenge of surfing. Publicity photos show her with a short wooden bellyboard.

There were many women eager to take up surfing as the sport’s popularity spread in the early decades of the twentieth century. They weren’t hindered by the long, awkward, swim dresses that caused Agatha Christie grief, but they had to face a wave of chauvinism that was not yet there when Agatha took to the waves. That didn’t stop determined women surfers from catching the next wave.

Mary Ann Hawkins was one of the first competitive female surfers. She won the Pacific Coast Women’s Surfboard Championships in 1938, 1939, and 1940, and made a name for herself as a stunt double. Hawkins was inspired to take up surfing after seeing Duke Kaahanamoku give a demonstration. She was a regular at what is now Surfrider Beach in Malibu in the years following WWII, and became friends with a young surfer named Darrylin Zanuck.

Darrylin was the daughter of producer Daryl Zanuck and an actress in her own right. She surfed for fun, not competition, but the board she used had a key role in the evolution of competitive surfing. In 1948, Zanuck’s boyfriend, surfer Tommy Zahn, commissioned legendary surfboard shaper Joe Quigg to make a short, light board for the five-foot-tall surfer. The Darrylin board weighed just 25 pounds and was compact enough to fit in Darrylin’s convertible. It became a prototype for the light, fast, maneuverable boards used today.

In the late 1950s, an aspiring teenage surfer named Kathy Kohner talked the boys at Malibu into letting her into their club. Kathy shared her adventures with her father, screenwriter and novelist Frederick Kohner. He turned them into the 1957 book “Gidget”. The movies based on the novel enshrined Gidget and ’50s California surf culture in the American consciousness.

In 1959, Linda Benson, a 15-year-old California surfer, became the youngest contestant ever to enter the International Championship at Makaha. She won, and followed the feat by riding a 20-foot wave at Waimea, Oahu. Benson would go on to win the U.S. Championship at Huntington Beach in 1960, 1961, 1964, 1968.

Benson’s success was not met with universal approval. Surf historian Jim Kempton, the author of Women on Waves, recounts how big wave surfer Buzzy Trent quipped he “couldn’t stand girls attempting to ride big waves.” It’s a good thing he wasn’t around to see Brazilian surfer Maya Gabiera ride a 73.5-foot wave in Portugal in 2020. It was the biggest wave of the year and the biggest wave surfed by a woman—so far.

We know about celebrity surfers because they talked about surfing in the media or were photographed with their surfboards in publicity photos. Agatha Christie’s passion for surfing was hinted at in one of her early novels. The Man in the Brown Suit, published in 1924, features an adventurous heroine who learned to surf in South Africa, but Agatha’s own love for and expertise at surfing was only revealed when her autobiography was published posthumously in 1977. Her letters and journal entries from that 1922 round-the-world trip, published in 2012, added more details to what we know about her love for surfing.

In Hawaiian culture, where surfing originated, both men and women surfed. In the 1920s, when surfing began to catch on around the world, men and women both participated, thanks in part to the traditional Hawaiian values embraced by the men who helped popularize the sport. Today, male surfers greatly outnumber female surfers—some estimates put the numbers at four to one. On a recent day at Westward Beach, when a big swell was powering perfect double overhead sets, the lineup was crowded with surfers but there were no women out there. I couldn’t help thinking of Agatha Christie, who once wrote, “swimming is a little tame after surfing…” If she had been there, she would have gone for it.