The fog comes

on little cat feet.

It sits looking

over harbor and city

on silent haunches

and then moves on.

—Carl Sandburg

Coastal Eddy isn’t a surfer, or a surf band from the 60s, but this West Coast phenomenon is a big part of what makes coastal Southern California so cool—literally.

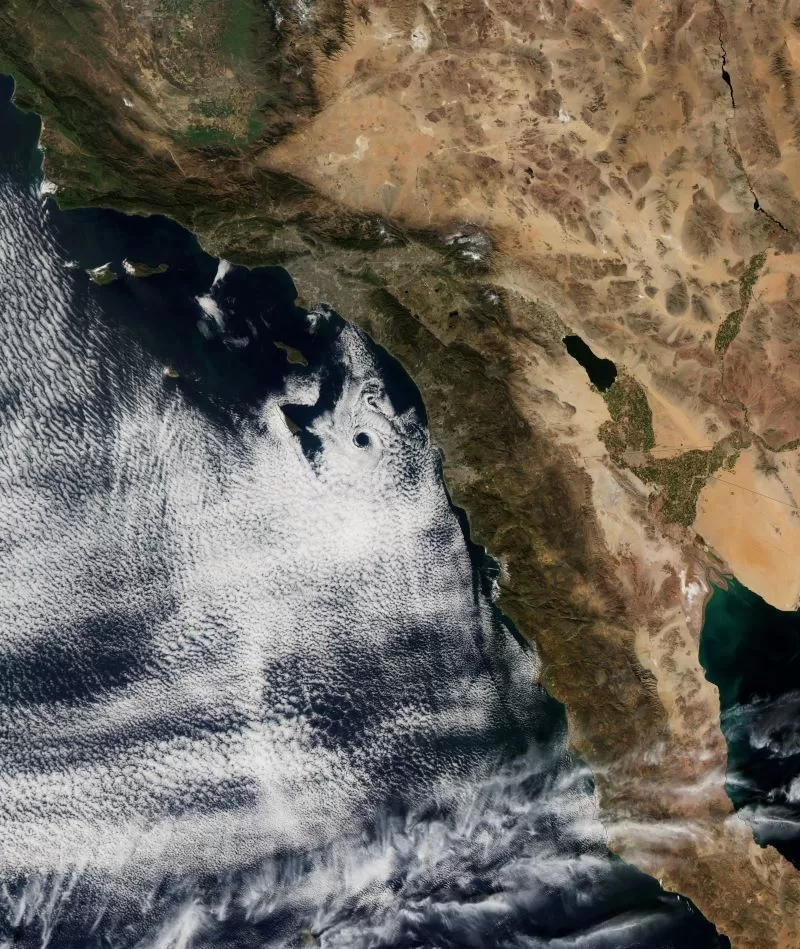

The Coastal Eddy, also known as the Catalina eddy, or just the marine layer, is a localized wind pattern, a current of air, that occurs during the spring and summer along the Southern California Bight—the crescent-shaped part of the coast that runs from Point Conception all the way down to San Diego.

The coastal eddy can form at any time of the year, but it is most common in late spring and early summer, when there is the biggest difference in the temperatures of land and sea.

The coastal eddy is responsible for the South Coast’s May gray, June gloom, no sky July, and Fogust. It can help keep the coast cool during the summer even when inland Southern California is broiling. It’s not unusual for it to be 100 degrees on the valley side of the local mountains, and 70 at the beach.

Officially, the influence of the coastal eddy peaks in June, but the marine layer is usually here all summer, and can form at any time of the year when conditions are right.

NOAA defines it as: [an eddy] that forms when upper level large-scale flow off Point Conception interacts with the complex topography of the Southern California coastline. As a result, a counter clockwise circulating low pressure area forms with its center in the vicinity of Catalina Island. This formation is accompanied by a southerly shift in coastal winds, a rapid increase in the depth of the marine layer, and a thickening of the coastal stratus.”

The marine layer is often used as a synonym for low clouds and fog, but it’s more like the cap that holds the fog in place. This inversion layer acts like the lid of a saucepan, while the coast ranges are like the sides of the pan, keeping the moist sea air and the clouds it generates from boiling over into the valleys. It’s the cat in Carl Sandburg’s poem that brings the fog, but it’s also like Lewis Carroll’s Cheshire cat, moving unseen, and manifesting itself in surprising ways.

When areas of low pressure deepen along the coast, building the marine layer to more than 6000 feet, that cauldron of cool, coastal air can pour over the coast ranges into the valleys, but mostly it lays close to the coast in the summer, bathing the ocean side of the Santa Monica Mountains in fog, and creeping through the canyons like a living thing, leaving the tops of the mountains like islands above a sea of clouds.

The Los Angeles Basin benefits from the cooling influence of the marine layer; so does the part of the Conejo Valley that receives a cooling flow of ocean moisture from the Camarillo grade, but unless its a thick marine layer, the coast ranges keep the cooler air at the coast and out of the valleys.

In the LA Basin, the coastal eddy not only helps to keep things cooler, it helps to improve air quality, reducing the impact of smog. The moisture that it brings is essential for a host of specially evolved native plants and animals, but also for the human beings who crowd into a city with lots of concrete and not much shade or green space. Without the eddy, LA would be a lot hotter and smoggier.

The coastal eddy is formed by a highly specific combination of elements. Sea and air temperatures, the rugged and mountainous coastline, and the shape of the bight—a specialized word that means a curved shoreline—all impact this cyclone-like counter-clockwise wind pattern, but it is part of a bigger pattern. The California Current System is a cold water current that moves south along much of California’s coastline, generating eddies and powering the seasonal upwelling of cold, deep water.

The CCS helps support and maintain one of the richest areas of biodiversity on the planet, but it could be at risk from climate change.

A 2022 study published by researchers from the University of California Santa Cruz, NOAA’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center and NOAA’s Physical Sciences Laboratory, suggests that the eddies may become “more variable and intense toward the end of the century compared to a 1980-2010 reference period.”

The findings, published in Geophysical Research Letters, predict that the changes will impact ecosystems and coastal communities, although the authors conclude that “the impacts of climate change on these CCS processes are poorly understood.”

Those of us blessed to live under the influence of the coastal eddy tend to take it for granted, but this atmospheric phenomenon always has the power to surprise. It can blow the fog in on a mighty wind, hiding the moon and stars in minutes. Sometimes it brings clouds that lingers for days or weeks, and fog that blankets the coast at night and lingers in dense pockets on the canyon roads. Sometimes it sits offshore, a tidal wave of cloud, waiting to break against the steep sides of the coast ranges. On other days the marine layer stays close to the coast, covering the beaches in overcast, giving canyon dwellers a sea of fog at their feet, and leaving valley residents to swelter in the heat. Drive from the floor of the San Fernando Valley on a hot day over Topanga Canyon Blvd. to the Pacific Coast Highway and feel the temperature drop as much as 30 degrees. That might mean a day of fog bathing instead of sun, but a cloudy beach day is a small price to pay for an escape from the inland heat. Thanks Eddy, you are one cool cat.