A new sign was recently installed by the side of Kanan Dume Road. It reads: “Sheila James Kuehl Nature Preserve at Ladyface Mountain.” It’s not the most imaginative or descriptive name for this rugged and beautiful mountainside, but this 325-acre section of open space was named in honor of an elected official who spent almost 30 years representing the Santa Monica Mountains in the state assembly, the state senate, and as a Los Angeles County supervisor. Kuehl is described as an early and key advocate of the multi-decade effort to preserve more than 1000 acres at Ladyface Mountain.

The Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area is often described as a patchwork of state, federal and local open space, stitched together to form the largest urban national park in the nation and potentially in the world. Each piece of the quilt has a name—some have more than one—and those names form their own patchwork of different historical periods and trends. It’s an evolving picture, as places are added and names change.

The oldest place names are derived from the original peoples of the Santa Monica Mountains—the Chumash and the Tongva. These names include Topanga—”the place above” in the Tongva language; Malibu—a Chumash name that means “where the surf sounds”; and Mugu, the name of the large Chumash community on the beach at the western end of the mountain range. Those three original Native American names are attached to the three biggest state park units in the Santa Monica Mountains, the three parks that provided enough open space for the National Recreation Area to be created in 1978.

Zuma Beach also has a Chumash name, from Sumo—”abundance,” the name for the Chumash population center in that area. Solstice Canyon comes from “Soston,” an attempt to pronounce the Chumash word for the settlement at the mouth of what is now Solstice Creek, Lechuza Beach and Arroyo Sequit are also derived from Chumash names. Lechuza, listed as “La Chusal” on the Plat map drawn up in 1870 by landowner Mathew Keller. That could be a misspelling of the Spanish word for “barn owl,” and also for an enigmatic shape-shifting witch woman from Mexican folklore, but it is more likely derived from the area’s somewhat similar sounding Chumash name, “Lisiqsihi.” According to Chumash language specialist Richard Applegate, Lechuza and Arroyo Sequit, both derive from Lisiqsihi. Applegate suggests the word was Ventureño Chumash for “beachworm.”

When the Spanish colonists arrived, they began naming landmarks for conspicuous features, but it can be hard to tell if a Spanish place name authentically dates to the Spanish and Mexican settlers of the late 18th and early 19th century, or if it was named by a prospective developer in the 20th century, hoping to cash in on the romance of the colonial era.

Las Flores is an old Spanish name, presumably given for the canyon’s abundant spring flowers; Tuna canyon and beach get their name from the native prickly pear cactus. Escondido means hidden, and Hondo means dry. These all seem to be authentic names.

El Matador—the bullfighter, El Pescador—the fish, and La Piedra—the stone—sound authentic, but these popular beaches only received their Spanish names after the state acquired them in the 1970s. They are all packaged together as Robert H. Meyer Memorial State Beach, named for a now forgotten state parks chief deputy director who died in 1978. Other park units named for politicians include Marvin Braude Mulholland Gateway Park, a 1,500-acre park in Topanga named for former Los Angeles City Councilperson Marvin Braude, and Zev Yaroslavsky Highlands Park in Calabasas, named for the former Los Angeles County Supervisor. Both men were advocates for the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area. Former Los Angeles County Supervisor Deane Dana was not. He actively opposed the creation of the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, and was a major proponent for massive development in this area, which makes it ironic that he, too, has a park named for him, but at least it’s across the bay from the mountains he tried so hard to pave over.

Before politicians became a source for place names, saints were popular. Most but not all of the saint names were bestowed by the Spanish colonists. The Santa Monica Mountains are named for a fourth century North African saint best known as the mother of Saint Augustine. Saint Monica wept for her son’s wild behavior before he settled down to become saintly. Folk legend says that the name was given to Kuruvungna Springs, a natural year-round water source still sacred to the Tongva people, in honor of “Las Lagrimas de Santa Monica”—the tears of the saint.

The first official record of the place name “Santa Monica” is on a prosaic grazing permit issued in 1828 to Don Francisco Sepulveda, who received the grant for the Rancho San Vicente y Santa Mónica a decade later. It is unclear when the name was extended to include the coast range. The earliest mention the author has encountered is in an account by Socrates Hyacinth—the eccentric pseudonym of author and artist Stephen Powers—printed in the January 4, 1969 edition of the Los Angeles Daily News. Hyacinth wrote, “I saw the Santa Monica Mountains, wandering lone and vast in the haze westward toward the sea…”

By the start of the 20th century, naming rights shifted to developers.

Water baron William Mulholland named the Mulholland Highway for himself, and most likely would have been disappointed to know that the six-lane thoroughfare across the core of the mountains that he envisioned never became a reality. Some names were bestowed by developers who did not think the original names had sufficient cachet. Paradise Cove Beach in Malibu was named by the developers of the original RV park. They didn’t think the names “Smuggler’s Cove,” or “Banning’s Harbor,” had sufficient cachet. Parker Mesa became Sunset Mesa for the same reason. The name Latigo Canyon—”whip” in Spanish—was also chosen by would-be developers in the 20th century. The romance of a Spanish name taking precedence over the more prosaic name Dry Canyon, given some time prior to 1870, according to early maps.

Names change for many reasons. Cora Trippet, who purchased a 86-acre property in Topanga in 1917 named the property “Las Lomas Celestiales,” “the Heavenly Hills.” Her heirs opted for using their family name instead, and when they sold the property to the state in the 1960s, the name remained simply “Trippet Ranch.”

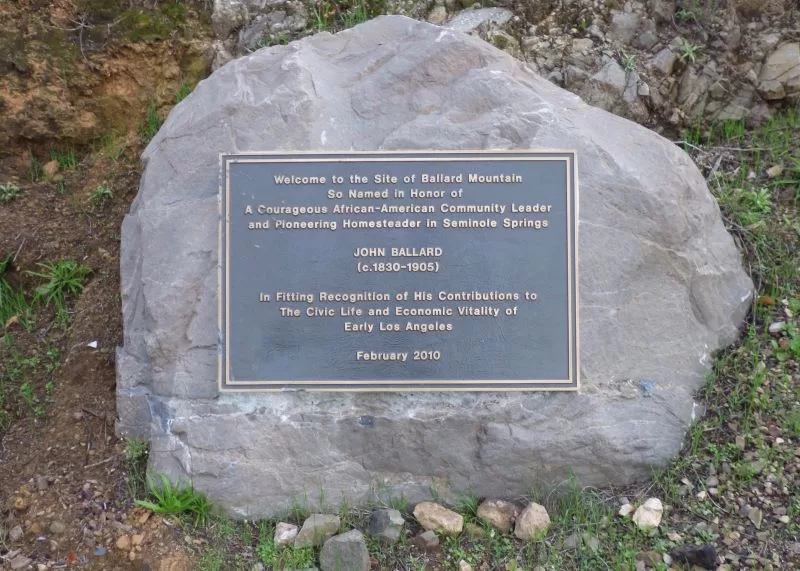

One recent name change righted a century-old wrong. Ballard Mountain in Agoura Hills was renamed to honor the African American homesteader who lived there in the 19th century and faced horrific discrimination. The new name replaces an offensive epitaph, and celebrates the courage and determination of John Ballard, not the cruelty of his neighbors.

Every name on every park, trail, road, and overlook in the Santa Monica Mountains was named by someone for something they deemed significant. We don’t always remember what those names mean, but they are part of the multi-layered history of the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, part of the pattern of a constantly evolving, one-of-a-kind national park.