The Coastwatchers chronicles the adventures of James Ellis Anderson, a young boy from Illinois sent to live with his eccentric aunt in Malibu during WWII. In the tradition of fiction from that period, TNT is presenting this original story by TNT Editor Suzanne Guldimann in serial installments in print and as an audiobook podcast, read by Claire Chapman. The first chapter, which introduces James and his Aunt Maddie, debuted in our November 4, 2022 issue and is available online. Please join us, as we travel back in time to 1942.

Have you ever heard of grunion? I hadn’t, not until my new friend Bob Henry told me about them. Grunion are tiny fishes that come up out of the ocean onto the wet sand when the tide is highest in spring and summer to lay their eggs. On some beaches there can be thousands of them, and the funny thing about them is, no one ever sees them except during spring and summer high tides, and just on Southern California beaches, nowhere else anywhere. Bob says he’d never seen anything like the number of fish that swam ashore on the night of the new moon that June, and that there would likely be more on the night of the full moon.

Bob is in the Coast Guard. He’s one of the guys stationed here in Malibu who patrols the coast, and he’s learned a lot about fish and other sea creatures. He said there were so many fish that the edge of the water looked like quicksilver and that June was the best month to see them. After hearing about that, Jessie and I wanted to see them, too.

It turned out that the highest tide of the full moon was just before dawn on the morning of the last Monday of the month. Jessie was all for sneaking out, and for all I know that’s what she did, but I felt like I owed it to my aunt to ask for permission. Luckily, she gave it.

The moon was far down in the west when I slipped out of the house before dawn. I wasn’t used to seeing it in that part of the sky. It cast long shadows and made everything feel strange and dreamlike, but there was plenty of light to find my way. Jessie, impatient and eager for adventure, was waiting for me on the beach path.

We were still under the new “Dim Out” rules, so we couldn’t use flashlights. The moon, which lit our way down the path, turned everything it touched to silver, but where it couldn’t reach was like black velvet. Almost as soon as we reached the beach, the moon dropped into the thick layer of clouds that sat offshore. The night became much darker.

As we picked our way cautiously across the beach towards the water we met Bob and his watch partner, a guy named Frank McGilicready, who everyone called Mac. We were nearly flattened by the third member of the crew, their dog Moose.

All of the coast patrol teams are assigned a guard dog. There weren’t enough military trained guard dogs to go around, so the government drafted people’s pet dogs. Moose’s real name was Bruno. He was supposed to be a German shepherd dog, but Bob theorized he was really part moose and the name stuck. He was the size of a small donkey and had one ear that stuck up and one that flopped down. Bruno was afraid of the dark, or maybe he just didn’t see well, so he stuck so closely to Bob and Mac that they were always tripping over him. If the enemy ever did land on the beach, Bruno would have greeted them with his tail wagging. He was a very friendly dog.

By the time Jessie and I had disentangled ourselves from Bruno’s enthusiastic greeting, and I had wiped my glasses on my shirt tail—Moose had bestowed many kisses on both of us with a tongue like a big, wet washcloth—my eyes finally adjusted to the dark. I gasped with surprise. The tide was almost full and came far up the beach but the sea was calm, with long glassy breakers that echoed like a roll of thunder when they broke on the sand, and all along the shore break, with every wave, there was a glow of faint, eerie blue light.

I’d read about phosphorescence—in the ocean it’s caused by tiny animals called plankton—but I’d never seen it or even imagined ever seeing it. Every step we took on the wet sand glowed faintly. I was enchanted. It was like magic, real magic.

Bob and Mac laughed at my amazement and reminded us that we were supposed to be looking for fish. They pointed us towards the stretch of beach where they had seen the most grunion and headed off on their appointed patrol route with Moose.

I had expected the whole beach to be covered with grunion but they were only on one stretch of shore. There were hundreds of them, thin, silvery fish washing in with the tide, struggling to scoop out a small depression in the sand to lay their eggs in. Then they wriggled down the sand again into the sea. Gulls and other birds were waiting to snatch up a fish dinner.

A lot of people catch grunion and eat grunion, too, but I felt sorry for them. Aunt Maddie told me that there used to be a lot more of them, and that special rules had to be put in place to protect them from people. We watched them for a while and then walked on, still under the spell of the bioluminescence.

We walked a long way, sometimes turning around and walking backwards for the fun of seeing our footprints glowing a faint, eerie blue. It was quiet except for the sound of the waves breaking, and very dark. We could see the rooflines of the houses along the Malibu Colony, dark against the sky, but there were no lights anywhere except starlight, and the faint phosphorescence, and the diffused glow from the horizon where the setting moon was hidden by the clouds. We didn’t talk for fear of breaking the spell. I was just starting to wonder what time it was and if we should maybe start back home when we spotted something in the surf a little further up the beach. It was long and thin and silvery and it writhed in the shallow water like an enormous snake.

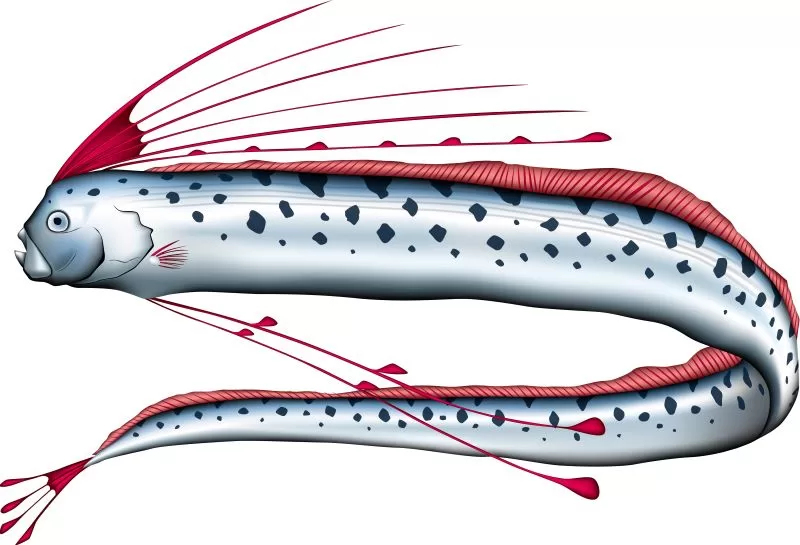

Jessie and I broke into a run. The thing must have been some kind of fish but it looked exactly like a sea serpent. It had long streamers growing from either side of its mouth, like a dragon, and a crest of sort of quill-like things.

The next wave swept the thing up onto the sand and left it thrashing.

“It’ll die,” I said.

“We have to save it,” Jessie said at the same time. “Or at least try. I wonder if it bites?”

“It has a tiny mouth and it doesn’t look like it has teeth,” I said, moving closer. “But it has a huge eye. It must be one of those deep sea creatures. I hope it’s not dead. It isn’t moving now. If I take this end, and you take the other, do you think we can tow it back out into the water?”

We tried. The sea serpent, or fish, or whatever it was, came back to life the second we touched it, flailing madly. It must have been fifteen feet long at least, and it was so smooth and slippery it was almost impossible to get a grip on it.

We struggled with it but couldn’t pick it up. We were gasping for breath just like the sea serpent, when a voice behind us said, “It’s a doomsday fish.”

Jessie and I nearly jumped out of our skins. A man was standing on the beach just a few feet away from us. He kicked off his shoes and waded in to help. Between the three of us, we got the creature back into the water. It gave a sort of shudder and took off, back out to sea. It left a faint blue wake of bioluminescence behind it. The three of us stood watching for a long time.

I realized it was getting lighter. I could see my companions as more than just dark shapes, and I was suddenly very cold.

“‘Leviathan,” the man said, breaking the silence. “‘He maketh a path to shine after him, and upon earth there is not his like.’”

He nodded at us, and walked swiftly back up the beach without another word, vanishing into a tall, narrow house with a steeply peaked roof.

“I think that was Mr Browning,” Jessie whispered to me. “You know, Alice Browning’s husband. He’s a recluse who never goes out and never talks to anyone.”

We walked home as quickly as we could. The fog came in as the sun came up, and it was gray and cold. All the magic of the past hour was dispelled and we were both chilled and hungry.

We talked on the way back, just like we always used to, and to keep our minds off of how unpleasant it is to walk in wet, sandy clothes.

“I’m sorry I was mad at you, James,” Jessie said, a little awkwardly. “I didn’t want to hear about your dad or your sister, but now my brother Dan is being sent to Europe, to Italy, so I sort of know how you feel.”

“It’s going to be OK,” I told her. “No matter what happens.” I didn’t know what else to say. “Come up to the house and warm up,” I invited her. “I’ll make some coffee.”

We sat at the kitchen table in companionable silence eating toast with honey. Aunt Maddie joined us, drawn by the smell of coffee brewing. “Did you see the grunion?” she asked.

“We saw a sea monster!” Jessie announced. “A man who helped us get it back out to sea said it was a ‘Doomsday Fish.’”

“It sounds like an adventure,” Aunt Maddie said. “Tell all.”

She cooked eggs for us while we told our story.

“Tod Browning? Seeing him is almost as unusual as encountering a sea monster,” Aunt Maddie said. “He’s a strange man—a gifted filmmaker, but a tormented one. He doesn’t make movies anymore. He rarely leaves the house now.”

“He called the sea monster a doomsday fish, but also “Leviathan,” like in the Bible,” I said.

“I’ve never heard of a doomsday fish, but I know where we might find one.” Aunt Maddie went out and came back with a battered old field guide to Pacific fishes.

“Does this look right?” she asked, showing us an illustration titled, Regalecus russelii, “the giant oarfish.”

“They are rare, or at least rarely seen,” she said, scanning the entry. “It says here that they can grow to be more than 25 feet long, and that they are sometimes called doomsday fishes because they are thought to bring warnings of earthquakes and other misfortune. I think seeing one was a rare blessing, not a misfortune. You’ve seen what very few people have ever seen.”

“Upon earth there is not his like,” I said, remembering the words Mr Browning had said, and savoring the memory of something strange and wonderful, something few people had ever seen or would likely ever see.