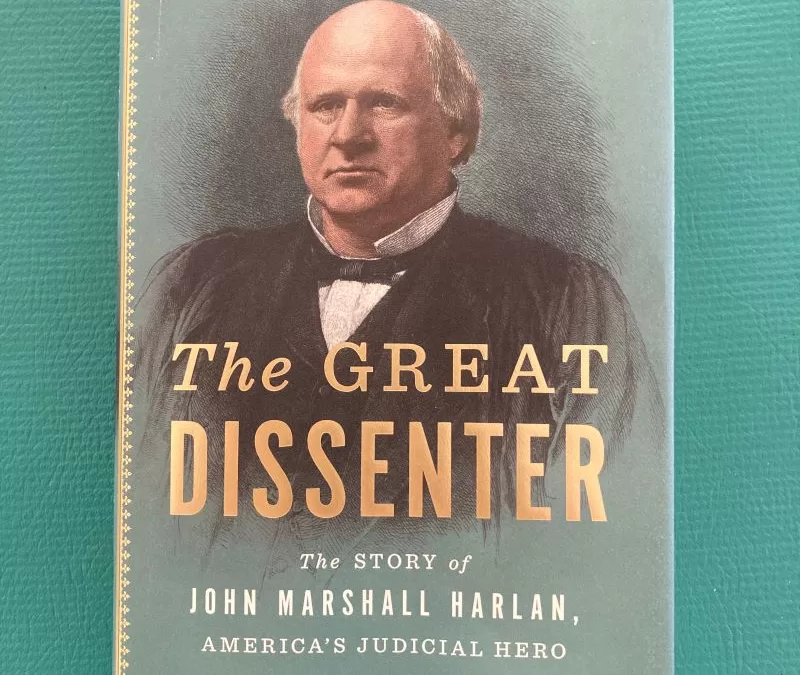

John Marshall served as Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1801-1835 and is largely seen as giving life and meaning to the third branch of our nation’s government. In 1833, a boy was born in Kentucky and his father, James Harlan, so admired this first great jurist of American history that he bestowed upon him a name that carried with it the highest of expectations. In The Great Dissenter: The Story of John Marshall Harlan, America’s Judicial Hero (2021), historian Peter S. Canellos tells the story of this boy.

Most notably, from 1877-1911, John Marshall Harlan served on the US Supreme Court while regularly dissenting with majority opinions that repeatedly rejected the clear language of the Civil War Amendments to the US Constitution. Not only did Harlan often stand alone, many of the dissenting opinions he crafted served as beacons for future courts that would use his dissenting language in the formation of new majorities upholding the letter and spirit of the Constitution.

John Marshall Harlan came of age in the 1840s within a slave-holding family as the country marched towards civil war. Along with Delaware, Maryland, and Missouri, Kentucky was a slave state that remained in the Union even as eleven other slave states seceded to form the Confederate States of America. When war came, Harlan recruited over 900 men into the 10th Kentucky Volunteers to defend Kentucky and the Union.

The tragic events that were tearing the country apart had a transformative effect on Harlan, as they did on many of the enlightened people of the time. One of the most significant factors in this transformation for him was the presence throughout much of his life of one Robert Harlan, by most accounts Robert was John Marshall Harlan’s half-brother and the property of their father, James Harlan. In this respect the biography of John Marshall Harlan also documents Robert’s life and his rise within a Black elite population that prospered across the Ohio River in Cincinnati and in Washington, D.C.

“The New York World,” Canellos writes, “went so far as to state that Robert’s ‘influence over his race was second only to that of Frederick Douglass.’”

Following parallel paths, Robert and John Marshall Harlan interacted with many of the more well-known figures of the day—including Douglass, William Howard Taft, and Ulysses S. Grant—before, during, and most notably for John, after the Civil War.

For a brief moment, it seemed as if that bloodiest of American conflicts had not been fought in vain.

In the decade or so following the war, nearly four million formerly enslaved African Americans experienced a previously unimaginable degree of social and political freedom. Southern white resistance to this development was tempered by the presence of federal troops whose mission was to oversee the re-establishment of Southern state governments in the spirit of protecting these newly-won civil rights while also promoting educational and economic opportunities for Freedmen.

Known as Reconstruction, these post-war advances in the South were made possible by a federal government willing to defend the Constitution during the two-term presidency of Civil War General Ulysses S. Grant (1869-1877).

This short-lived expression of Black freedom ended abruptly.

As a result of the contested presidential election of 1876, a re-invigorated white Southern Democratic party struck a bargain with a new generation of Republicans that had tired of overseeing the South. It was agreed that Republican Rutherford B. Hayes would become president in return for the withdrawal of federal troops from the South.

With no federal presence, state and local governments in the South came to be dominated by the same forces that had waged civil war against the United States. Organizations such the Ku Klux Klan terrorized Southern Blacks who dared to exercise their rights, hundreds were lynched or killed in mob violence, and in a very short time, laws were passed that severely limited the social, economic, and political rights of African Americans.

Reconstruction was over and the era of Jim Crow had begun. Canellos cites Frederick Douglass, who recognized that without federal support, Southern whites would reassert their authority over the formerly enslaved: “Oh you freed us! You emancipated us! I thank you for it! [But] when you turned us loose, you gave us no acres; you turned us loose to the sky, to the storm, to the whirlwind, and, worst of all, you turned us loose to the wrath of our infuriated masters.”

With a Constitution now purporting to abolish slavery, guarantee equality before the law, and protect voting rights—Civil War Amendments 13, 14, 15—it was up to Congress to enact legislation protecting these Constitutional rights and for the president to enforce the law. However, challenges to Reconstruction-era legislation amid the worsening conditions in the South after 1877 made their way to the Supreme Court.

Unfortunately, the large majority of justices on the Court during these years was much more concerned with reconciling North and South rather than protecting African American rights. There was one dramatic exception. In the same year that Rutherford B. Hayes took office under the suspicious circumstances that ended Reconstruction, John Marshall Harlan joined the Court. Over the course of more than thirty years, Harlan earned the moniker of Great Dissenter.

In US v. Harris, 1883, the Court ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment applied only to state action and not to the actions of individuals; meaning the federal government could not prosecute a Tennessee sheriff and four others for conspiring to lynch four Blacks. This narrow interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment served as a message to Southern whites that the federal government was not inclined to intervene in their affairs. John Marshall Harlan dissented.

In the Civil Rights Cases, 1883, the Court ruled that parts of the Civil Rights Act of 1875 were unconstitutional because the federal government had no power to outlaw private acts of discrimination based upon race. John Marshall Harlan dissented.

In Plessy v. Ferguson, 1896, the Court established the standard of “separate but equal” which validated Southern laws separating the races. This official validation of segregation stamped Southern Blacks as second-class citizens whose civil rights, allegedly guaranteed by the US Constitution, were subject to the whims of those who had been defeated in the Civil War. This is John Marshall Harlan’s most famous dissent.

“The white race deems itself to be the dominant race in this country…,” Harlan writes in his lone dissent in Plessy, “but in the view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our Constitution is color blind… In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law.”

A straight line can be drawn from this lone voice in 1896 to Brown v. Board of Education, 1954, which overturned Plessy in a 9-0 vote and nurtured the modern Civil Rights Movement.

In other dissents, Harlan defended the right of the federal government to impose an income tax, supported the regulatory power of the government to break up monopolies, and argued that the people in lands acquired by the United States – specifically Hawaii, the Philippines, Guam and Puerto Rico – were protected by the US Constitution.

Despite his singular efforts, there was little doubt at the turn of century that white supremacists had reclaimed control of the South. Securing this power for most of the twentieth century meant limiting Black Participation at the ballot box. Just as appears to be happening today, the Court determined in Giles v. Harris, 1903—with John Marshall Harlan dissenting—that federal power could not be used to stop Alabama from limiting Black voting rights.

By the time John Marshall Harlan died in 1911, Southern whites, emboldened by a passive Supreme Court, had begun crafting a revised narrative of the Civil War; one that glorified the bravery and sacrifice of the Confederacy, one that elevated Southern military leaders to new heights of celebrity, and one that portrayed the meaning of the war as a noble endeavor to protect the states from an overbearing federal government.

A generation removed from the horrors of the war, the enduring myth of “The Lost Cause” was born while many of the symbols of that crusade were rebranded and, very often, literally carved into stone. It is no coincidence that some of those same symbols have recently been resurrected in another effort to revise the narrative amid nostalgia for another mythical American past.

It is only through the courageous dissents of John Marshall Harlan that we are able to glimpse how the country may have moved forward after the Civil War. However, it is also through these dissents that the struggles of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s gained purchase, drawing directly from his language to clarify a healthier and more just interpretation of the Constitution.

Today, the Supreme Court seems poised to turn back the clock on many of these gains. As they do their dirty work, take hope that there are also members of the Court who see things as John Marshall Harlan did; and they are using the power of dissent to voice their concerns.