Dickey Chapelle’s career as a war correspondent began in the Pacific Theater of Operations in the waning months of World War II in 1945 and ended tragically, yet somehow fittingly, while on patrol with US Marines during the Vietnam War in 1965.

Her extraordinary story is told by Lorissa Rinehart in First to the Front: The Untold Story of Dickey Chapelle, Trailblazing Female War Correspondent (2023).

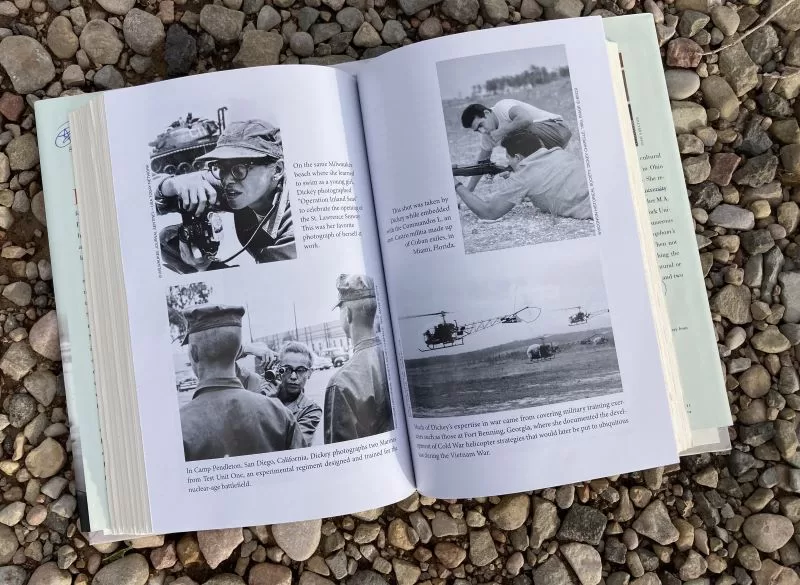

For twenty years, Dickey – a story demanding first-name familiarity – traveled the globe at the dawn of the nuclear age in which the world’s superpowers avoided direct conflict and, instead, engaged in a litany of proxy wars that devastated those caught in the crossfire; including Korea, Hungary, Lebanon, Algeria, the Middle East, Cuba, and Vietnam. Along the way, Chapelle repeatedly aimed her lens – metaphorically and literally – at those unwittingly caught up in the tragedy of these events; which stands in stark relief to the widely documented motivations and behaviors of those who brought them about.

As Rinehart affirms, “Like no other reporter, [Dickey Chapelle’s] body of work forms a complex tapestry of one of history’s most complicated eras.”

As a freelance journalist, Dickey often found herself struggling to make ends meet. While she pitched her ideas to a wide variety of outlets that published her work; Reader’s Digest, National Geographic, Look, the Saturday Evening Post, and more, the great body of her words and pictures were not published. They are available now only due to the preservation efforts of her family. It is this more private collection of materials upon which Rinehart draws refreshing insights into Dickey’s attitudes toward war, her compassion for all of humanity, and her ruminations on the nature of war.

While the conflicts Dickey covered have been well-documented, her unique perspective – as a woman and as a daring and passionate human being – moves away from the machismo that seems to dominate a great deal of military history writing. Drawing from Dickey’s autobiography published in 1960, Rinehart explores two early events that shaped Dickey’s outlook for her entire career.

In February of 1945, from the island of Guam in the western Pacific Ocean, and armed with a freshly minted press pass, a camera, a pen, and a notebook, Dickey Chapelle boarded the USS Samaritan, a hospital ship bound for the volcanic island of Iwo Jima; only recently invaded by Allied forces and upon which some of the bloodiest days of World II were about to occur.

Making her way through the vast ship on her first day aboard, Dickey came across the area where much of the crew’s work would be done. As the Samaritan chugged toward Iwo Jima, Dickey reflected later, “[a] hospital ship is the only vessel that goes into combat empty.” Engaging with the crew and medical personnel, including a robust nursing corps, Dickey was able to connect with those who became witness, not to the gritty chaos of the battlefield but rather, to the very physical toll that battles take upon the human body. “The one task of everybody aboard,” Dickey wrote, “is to produce enough humor to suppress the significance of all those acres of empty beds.”

Shortly after arriving off Iwo Jima, those “acres of empty beds” were filled with wounded soldiers – 700 hundred of them – attended by those trying to save those whose bodies had been torn apart… but only after deciding who among them could be saved… all the while slipping and sliding through the blood that covered the floor.

At first, Dickey was compelled to insulate herself from the carnage.

“Some part of my mind,” Dickey wrote later, “warned me that if I thought of them as people, just once, I’d be unable to take any more pictures and the story of their anguish would never be told since there was no one else here to tell it.”

“She didn’t maintain the detachment for long,” Rinehart writes. “Pausing to reload her camera next to the stretcher of a man she presumed to have already expired, she saw his hand move and looked up. His eyes opened. The deep lines of volcanic ash on his face began to stretch. She realized he was trying to smile.” When she asked how he was doing, he replied, as Dickey recollected in her autobiography, “I’m lucky… I’m here. I’m off the beach. I never knew the guys cared enough to get me the hell out of there. But they did. Three miles they carried me. Makes a guy feel lucky.”

“Two corpsmen came for his stretcher. Dickey quickly jotted down his dog tag number in her notebook” and asked the soldier his name. She then “watched as they set him down again in a corner of the deck for those who had arrived too late, who had lost too much blood…”

“From then on,” Rinehart adds, “she looked each man squarely in the eyes before she photographed him, acknowledging his anguish and fear, but also his hope.”

At one point, a Japanese soldier arrived on a stretcher even as some walking wounded GIs had not yet been let aboard. Fearing violence, Dickey watched the scene unfold. A bloodied Marine, whose “ragged jacket was in bloodstained ribbons and his left arm [was] in a sling… moved toward the Japanese soldier. The deck officer lifted his pistol. Leaning over the Japanese soldier, the Marine moved his hand toward the trench knife hung on his hip, then grazed past it and reached into his pocket. He took out a pack of cigarettes, removed one, placed it between the Japanese soldier’s lips and lit it.”

After being asked to donate blood on her way to Iwo Jima and then witnessing the shedding of so much blood on the Samaritan, Dickey made it her mission to do her part. A few months later, she convinced a Navy commander to allow her to actually land on Okinawa, the next great battlefield of the Pacific war.

As Dickey wrote later, she told the commander, “Sir, I’m photographing the use of whole human blood to save the lives of the wounded. Request permission to visit the Army’s blood stockpile on Brown Beach. Sir.”

In the early days of the invasion of Okinawa, unlike the attack on Iwo Jima, many beaches were secured by Allied forces. The commander gave her permission to visit Brown Beach and then return to the ship.

In this environment Dickey convinced the commander that it was “safe for a woman,” although, she also countered that, after what she had seen, this battlefield stuff wasn’t safe for anyone. “But if we are going to have wars,” she went on, “if we are going to find ourselves as a nation in a position where men must kill and be killed for months, even years – than [sic] no one except a woman can tell the story to other women.”

While on Okinawa – long overstaying her permission, by the way – Dickey witnessed the battlefield. The Okinawans had been living under Japanese occupation for years and an Allied victory allegedly included returning this island to their control. Rinehart captures a sentiment that Dickey would share time and again as she witnessed the decimation of civilian populations, especially later in Vietnam. “Last I heard,” she snapped, “we were liberating the Okinawans from the Japanese. They weren’t our enemies. So do you mind telling me why you had to smear their mud huts all over the map?”

There seems to be a general consensus that civilian casualties during war are inevitable. Dickey Chapelle has suggested that this heartless view, combined with the demonization of enemy soldiers, offers perpetual justification for war itself. For, when we begin to see the individual humanity in even our most aggressive adversary, we begin to carve out a small space where the peace might grow. And, as we have seen throughout our history, the actual warmongers are often simply the powerful few while the war fighters are us.

There is much more to this wonderful story but I’ll serve as spoiler only to the degree that Rinehart’s book jacket does: “She documented conditions across Eastern Europe in the wake of World War II… marched down the Ho Chi Minh Trail with the South Vietnamese army and across the Sierra Maestra Mountains with Castro… survived torture in a communist Hungarian prison… dove out of planes, faked her own kidnapping [and became]… the first American female journalist killed while covering combat.”

Throughout her adventures, Dickey consistently sought out those beaten down by war; the wounded GI, innocent civilians, refugees, and yes, even the enemy. She saw in all of them the bond that ties all of the planet’s peoples together.

In the complicated world of then and now, the lessons offered by the example of Dickey Chapelle seem rather simple. The most profound of these, captured in Lorissa Rinehart’s exceptional telling, is a compassionate and ultimately effective treatise which proclaims that if war should become necessary; it must be carried out with peace in mind.

While this human lesson may seem rather obvious, our own recent history suggests that there are simple lessons yet to be learned. Therefore, your history homework is to read this fine book and then let me know what you think.