“Believe me my young friend, there is nothing—absolutely nothing – half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats.” —Kenneth Grahame, The Wind in the Willows

Grahame’s endearing Water Rat wasn’t the only one enamored with boats in the early years of the twentieth century, when the emerging upper middle class found themselves with time and money for hobbies like sailing and boating. Private, custom yachts had been a luxury embraced by European royalty since at least the seventeenth century. English King Charles II brought the yacht back from exile in Holland, taking the idea of small, fast, self-sufficient sailboats called “jaghts” back with him when he assumed the throne, and turning it into a luxurious pleasure craft that he used to cruise up and down the river Thames. Charles commissioned as many as 20 yachts. He’s been described as the world’s first yachtsman, which might have surprised the Dutch sailors who had used this style of boat for hundreds of years, but he certainly helped to popular this type of craft and the whole romantic image of sailing as “the sport of kings,” or at least, the sport of wealthy people with disposable income.

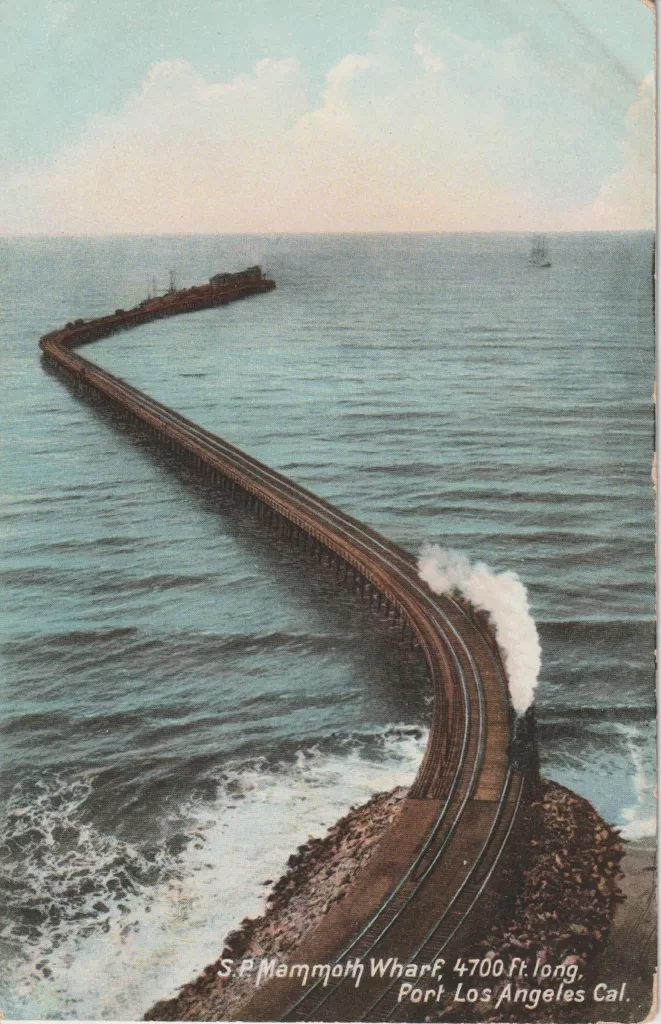

Self-styled yachtsmen took to the water in droves, and it wasn’t long before yacht clubs were organized to accommodate the boating lifestyle. Yacht clubs flourished on America’s East Coast, beginning with the celebrated New York Yacht Club, established in 1844. By the 1920s, the craze had reached California, and there was a push for yacht harbors in the Santa Monica Bay.

In 1924, the Los Angeles Athletic club paid the princely sum of $400,000 to purchase a mesa near Santa Monica Canyon where their country club and beach house still stand, but the organization also bought a swath of lower Topanga with the goal of building a private yacht harbor.

“The possibilities of an ideal yacht harbor have been carefully investigated and when the breakwater has been constructed one of the finest harbors in this section will be available for yacht purpose,” enthused the Los Angeles Times in September 1924.

Topanga wasn’t the only yacht harbor planned for the area. Another was proposed in 1926 as part of the La Costa and Malibu Colony developments in Malibu. The February 1947 issue of Californian Magazine has this to say about the plan: “ [May Knight Rindge] floated an $8 million bond issue and plans were drawn for lush clubs, a yacht harbor and other accouterments of a proper Riviera.”

May Rindge became the sole owner of the 17,000-acre Malibu Rancho when her husband, Frederick Hastings Rindge, died in 1905. In 1926, she leased the land at the Malibu Colony for what she thought would be temporary beach cottages, and began plans to develop a more permanent housing tract along La Costa Beach. She needed the money to fund her increasingly expensive fight with the county and the state over what is now Pacific Coast Highway—a fight she lost. May had a personal interest in a Malibu yacht harbor; she owned a 100-foot motor yacht, named Malibu.

Silent era actor Neil Hamilton, one of the first residents of the Malibu Colony, also owned a yacht, a sailboat named the Digby for his role in the 1926 film version of Beau Geste. He often anchored it off Malibu, and the society columns of the time boasted that a harbor to sail the boat into was expected to be an imminent reality.

May’s yacht is still afloat—it is now a registered City of Seattle Historic Landmark—but the plans for a Malibu yacht harbor in the 1920s were scuppered when Harold Ferguson, the man in charge of the development, was sent to San Quentin for shady business dealings. The bondholders foreclosed, leaving May Rindge, now more deeply in debt than ever, to cope with the aftermath. She filed for bankruptcy and her yacht was sold.

The 1920s Malibu yacht harbor would probably never have become a reality. Ferguson’s chief skill appears to have been building pyramid schemes, not harbors. Building a marina, even a small one, is complicated and costly. In the late 1920s, proponents of a Santa Monica yacht harbor confidently stated that a breakwater there would create “one of the finest yacht harbors in the world.” The first pile was driven in October of 1930, 450 feet off of the Santa Monica Municipal Pier. In 1937, lawsuits were filed because the breakwater was causing massive beach erosion. By 1945, when the beach south of the harbor had almost entirely disappeared, there were calls for the breakwater’s removal, and newspaper editorials called the harbor a costly failure.

The Santa Monica Yacht Harbor revealed a lack of understanding of shoreline dynamics, including littoral drift—the way wave action transports sand—and what happens when humans interfere with that process, but it didn’t quell the desire for more yacht harbors in the Santa Monica Bay.

A generation after the first Malibu yacht harbor plan foundered, plans for the Malibu Quarterdeck Club and Yacht Harbor materialized. The project was the brainchild of Edward D. Turner, who styled himself “the Commodore.” Turner saw the Malibu Lagoon as “a site for the construction of a yachting center in the Southland comparable with the famed Miami Quarterdeck Club.”

Cliff May, the architect famed for developing the California ranch house, was enlisted to design a clubhouse and surrounding grounds in a “style reminiscent of the South Seas.” The plans called for “hand-hewn redwood with aquamarine tile roofing. A glass windshield, constructed of specially treated glass and metals and inverted like the prow of a ship, will be placed atop the breakwater to protect bathers and those dining on the outdoor terraces and in dining rooms,” plans for the project state.

“Within a year it is hoped that this prediction will have become a reality,” a puff piece in Californian Magazine enthused. “Motorboats and yachts of club members should, by then, be able to anchor in the dredged-out creek delta. And in another year the ultra-modern Quarterdeck Club, designed by Cliff May, should be abuzz with its 1000 members bent upon getting their two thousand dollars worth of pleasure. Plenty of opportunity will be offered [to] them.”

The plans included slips for 750 small craft in the inner harbor, with room for larger vessels along the outer breakwater. A “ two-story boat garage equipped with boat elevators” would providing ‘valet’ service for parking pleasure craft up to thirty feet long. “This is a Riviera development of no mean sort,” the developer proclaimed.

Not everyone was enthused. Rhoda Adamson, May Rindge’s daughter, who owned the Adamson House with her husband Merritt Adamson, vehemently opposed the plan, as did William Huber, the owner of the Malibu Pier, and other members of the community, including the post-WWII generation of surfers, who became some of Malibu’s first coastal activists. The battle raged for over a year in front of the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors.

One of the main arguments is the one that would lead eventually to the Coastal Act and the formation of the Coastal Commission: public access. Opponents, including surfers, argued that the private yacht club would bar the public from the beach and destroy an important public resource.

Like Ferguson, Turner had no experience with coastal engineering, but that didn’t stop him. In September of 1947, Turner began excavating for the foundation of the yacht club. He did it without first obtaining permits. In November he held a BBQ in the Malibu Colony celebrating the driving of the first pile for the clubhouse. He died two weeks later, leaving his stockholders scrambling and the Quarterdeck Club in limbo.

For several years after Turner’s death, supporters of the project continued to produce press releases stating that construction was imminent, but it wasn’t until the county released plans to build a multi lane freeway through Malibu Canyon that the yacht harbor project was revived.

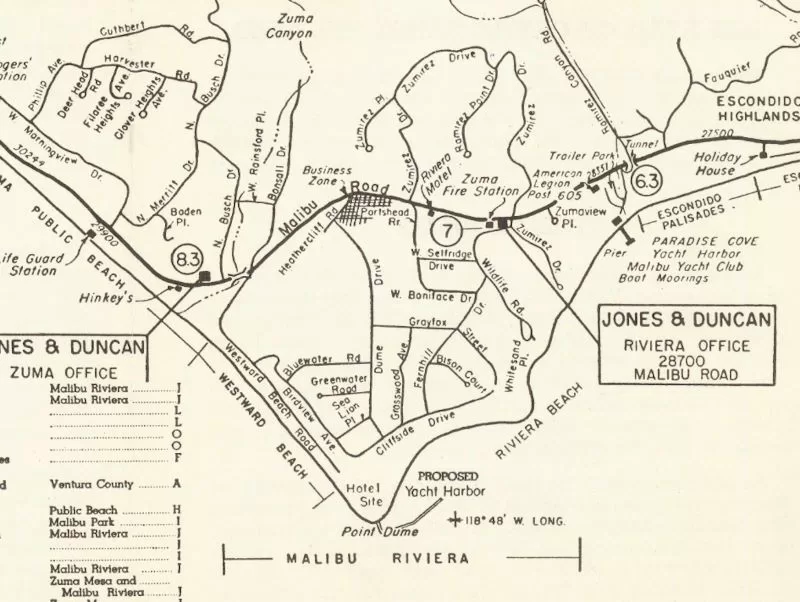

The final effort to develop a Malibu yacht harbor was floated in the 1960s. This plan was spearheaded by Henry Guttman, president of the Malibu Improvement Association. His plan was to use the hundreds of tons of rubble that would theoretically be blasted from the mountains for the freeway to build a breakwater, harbor and 300-home country club development, but his only experience in the field of development and urban planning was a row of modest office buildings on Malibu Road between the fire station and Webb Way.

“One of Malibu’s fondest dreams, that of establishing a small craft harbor, with all its attendant lodging, dining and recreational facilities, now seems closer to reality,” a 1966 brochure advertising the proposed marina states.

“The county has approved the idea of private financing for the harbor and the Federal Government has expressed interest in the project since being assured space within it for Coast Guard facilities, all that remains is the lease negotiations with the state, bilateral approval of the overall project, and completion of the various stages of development leading up to the Marina as planned by the Improvement Corporation and the state.”

Guttman used statistics released by the Los Angeles Regional Planning Commission in 1966 to help sell the project to skeptical residents and authorities. The county, in a fit of near delusional mid-century optimism, projected that the population of Malibu would reach 117,000 by 1980. That was partly thanks to Supervisor Burton W. Chace, whose district included the entire Los Angeles County coast, and whose goal was to transform the local coast into a yachting and resort destination, a sort of Miami Beach West.

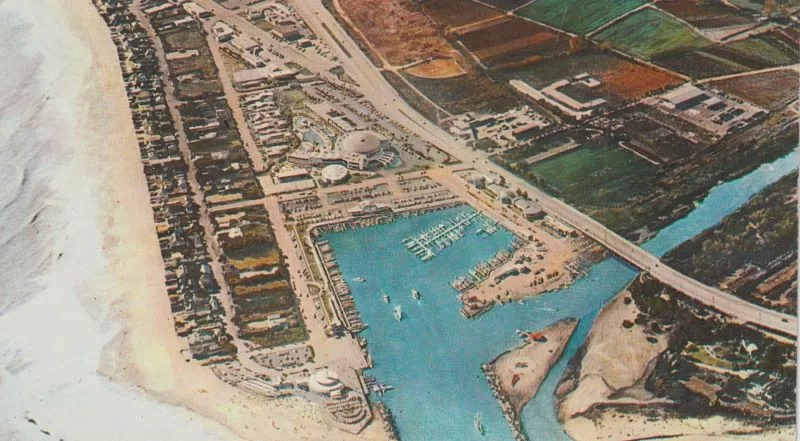

Chace helped facilitate the construction of Marina Del Rey, “the largest small craft harbor in North America.” That project, which converted 800 acres of salt marsh and wetlands into a new city and a harbor that could accommodate 5000 vessels, broke ground in 1953 and was completed in 1965.

Chace set his sights on Malibu, but at Point Dume this time. There was talk of building a breakwater and a harbor at Big Dume Cove as early as the 1930s. The proposal gained momentum in the 1960s. Topanga landed back on the county’s list of potential harbors during this time, too, with a breakwater, boat ramp and buoys to accommodate small craft.

The plan for Malibu that was endorsed by Burton Chace surfaced in 1971. It featured a full marina at Paradise Cove, with a breakwater, 1,430 boat slips and mooring for an additional 230 boats at offshore buoys, but the tide had turned against Chase. A coalition of environmental and surf activists pushed back against the proposal. Chace was killed in a car accident in 1972. Without his support, the Malibu marina plan crumbled under an angry wave of opposition.

Chace’s vision for Malibu fell far short. As of 2021, the population was 10,429, down from an all-time high of 14,126 in 2017. The last yacht harbor plan for the local coast came in the 1990s, when a Ventura County politician proposed a Marina Del Rey type development at Deer Creek just west of the Los Angeles County line. It sank almost as soon as it surfaced.

The Malibu and Topanga lagoons and the Point Dume headlands became state park properties in the 1970s. Point Dume, including Paradise Cove, is now part of a State Marine Preserve. Deer Creek was recently acquired by the Mountains Recreation and Conservation Authority for permanent open space.

Burton Chace succeeded with Marina Del Rey—he has a park and a major road named for him—but his dream of yacht harbors on the Malibu coast was never realized. It’s a relic of the mid-century passion for overzealous mega projects that also included freeways, causeways, mountaintop cities, and a nuclear power plant. On this coast at least, that ship has sailed.

The Topanga Lagoon is currently in the public input phase of an ambitious, multi-agency project to restore the Topanga lagoon, now recognized as critically important wildlife habitat, and celebrated for its surf break, instead of for its potential for recreational boating. Learn more at www.rcdsmm.org/topanga-lagoon-restoration/