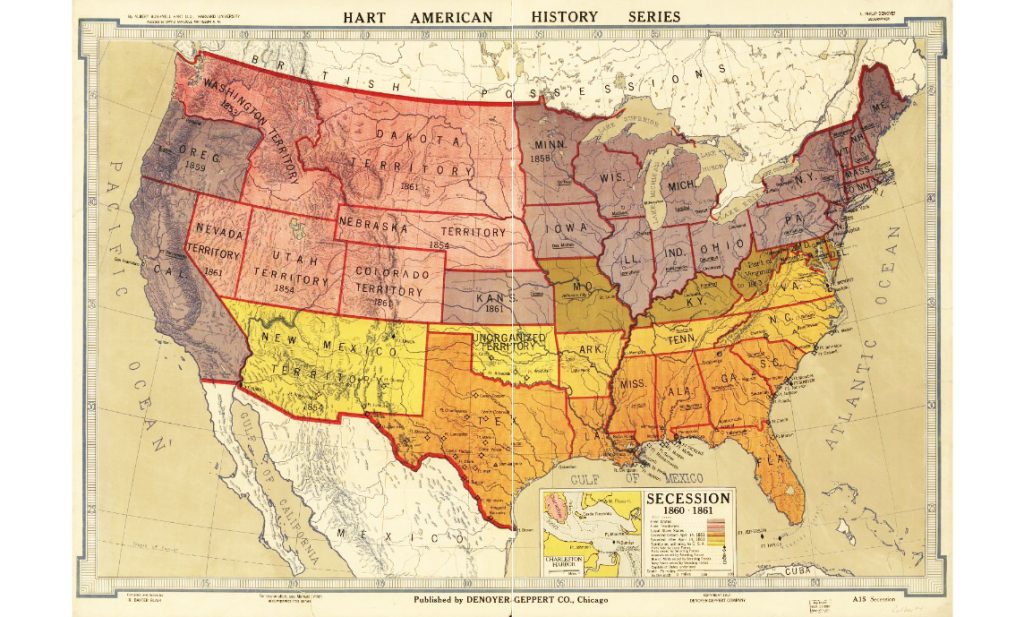

Following the election of Abraham Lincoln to the White House on November 6, 1860, the slave states of the American South pondered secession. By the time Lincoln actually took office on March 4, 1861, seven states had officially declared their withdrawal from the Union. Eight slave states remained, including Virginia. It was clear to all that Virginia’s decision, as the largest of the Southern states, would weigh heavily upon the other states.

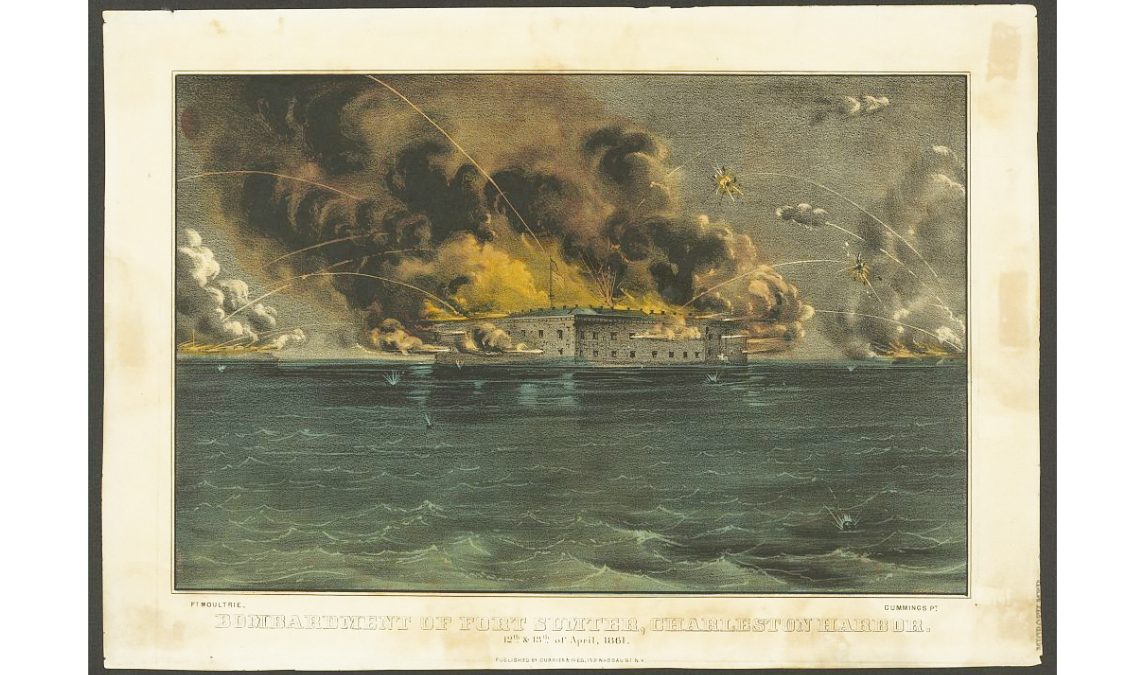

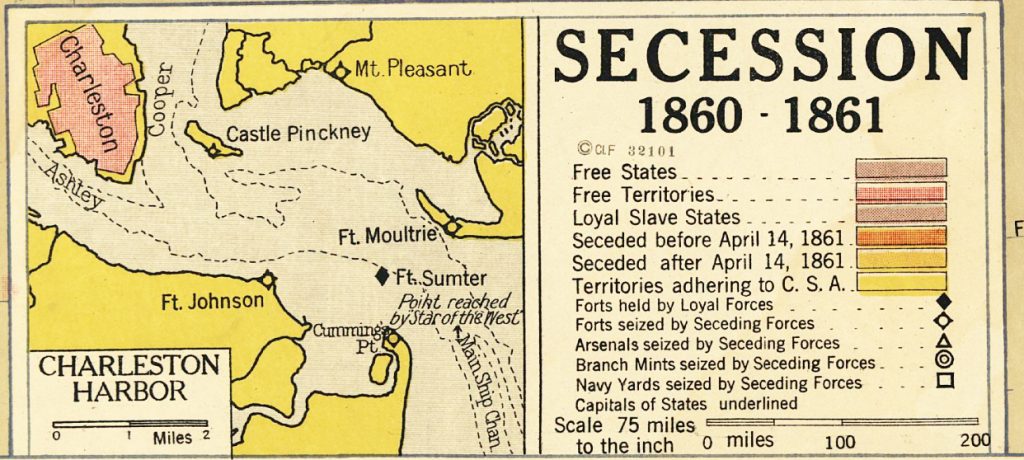

By April 1 of 1861, Virginia’s secession convention of 152 elected delegates had voted on two different occasions to remain in the Union. On April 12-13, forces of the Confederate States of America bombarded Fort Sumter, a federally held fort in Charleston Harbor. On April 17, Virginia voted to secede.

By June, Arkansas, North Carolina, and Tennessee also voted to secede bringing to eleven the number of states that waged war against the United States for the next four years. Seven hundred fifty thousand Americans perished.

In many American history textbooks, and in my American history classroom, the bombardment of Fort Sumter has been portrayed as a spark that set off an explosion that was bound to happen; that the country’s growing divisions over slavery could only be settled on the battlefield. After reading, The Demon of Unrest: A Saga of Hubris, Heartbreak, and Heroism at the Dawn of the Civil War (2024) by Erik Larson, however, I discovered that the six months between Lincoln’s election and Fort Sumter’s attack were filled with a variety of paths not taken; and that civil war was not inevitable.

Playing “what if?” with history does nothing to change the past. Yet, when the circumstances of “then” so resemble the circumstances of “now,” examining the “what ifs?” has the potential to inform the current situation. This is especially relevant when we look at the periods of our history when things went so terribly wrong.

In the case of the American Civil War, we can dial the clock back to the decision to bring “twenty and odd” Africans to Virginia in 1619. We might also fret over the failure to make real the lofty words—which were shouted to the entire world—that ours was a country where “all men are created equal.” As the nation expanded during the first half of the nineteenth century a series of compromises were made that served only to soothe the passions of the moment; this too could have been handled differently.

By the 1830s, with slavery thriving in the American South, the movement to abolish the “peculiar institution” gained momentum. This effort included the distribution of anti-slavery newspapers and pamphlets throughout the South which, in turn, led Southern slaveholders, fearing that the words would lead to insurrection, to double down on their defense of slavery.

What had once been an argument based on property and states’ rights shifted to claims that slavery served the interests of the enslaved, that servitude was their natural condition and that they had no desire to be set free where they would be unable to care for themselves.

In what Larson describes as “the first unabashedly pro slavery speech Congress has ever heard,” twenty-eight year-old Congressman James Henry Hammond orated, “As a class, I say it boldly, there is not a happier, more contented race upon the face of the earth than our slaves.” This was February 1, 1836.

Fancying themselves as a sort of nobility—the chivalry—slave owners, as Larson writes, “had persuaded themselves [that] Slavery was a positive good; it was endorsed by the Bible and by anthropological observation; even two famed Northern anthropologists… had proclaimed on the basis of purportedly scientific research that the Black race was not only inferior, but a different species altogether.”

By 1860, as Larson demonstrates, the Southern defense of slavery had become a matter of honor. “[T]he thing that the South most resented was the inalterable fact that the North, like the rest of the modern world, condemned slavery as a fundamental evil. In so doing, abolitionists and their allies impugned the honor of the entire Southern white race, for if slavery was indeed evil, then the South itself was evil, and its echelons of gentlemen, the chivalry, were nothing more than moral felons.”

Southerners also made broad assumptions about Lincoln’s intentions. “At no time,” Larson writes, “had he threatened to abolish slavery or emancipate the millions of enslaved men and women who populated the plantations of the South. But fire-eaters and secessionist editors had portrayed him as seeking just that.”

If the South misunderstood Lincoln, who swore to leave slavery alone where it already existed, the president-elect also misunderstood the South. Larson cites a letter Lincoln wrote to a Georgia congressman on December 22, 1860. “You think slavery is right and ought to be extended… while we think it is wrong and ought to be restricted. That I suppose is the rub. It certainly is the only substantial difference between us.” This was only two days after South Carolina had seceded and the other Southern states like Georgia were deciding whether to follow suit.

Within the vacuum created by the fundamental misunderstanding of each other’s motives, the demagogues stepped in to fill the void. And, the symbolic focal point of their wrath was Fort Sumter. Unfortunately, while Southern agitators rallied more states to secede, Abraham Lincoln was powerless to act.

Inauguration Day was not until March 4. Further, with the Congress set to certify his electoral victory on February 13, 1861, there was concern that this process might be disrupted; Washington, DC became an armed camp.

So, January 6, 2021 was not the first instance when this largely ceremonial process was seen as an opportunity to foment chaos. Larsen draws a clear parallel to then and now. He warns the reader at the outset. After reading The Demon of Unrest, he writes, “I suspect your sense of dread will be all the more pronounced in light of today’s political discord, which, incredibly, has led some benighted Americans to whisper once again of secession and civil war.”

During this tumultuous time, the federal troops at Fort Sumter were running out of rations, the Confederate Army was surrounding the fort on all sides with cannon emplacements, and President James Buchanan, as Larson thoroughly documents, was simply hoping that war would not begin on his watch. “What Buchanan needed,” Larson surmises, “was ninety days of peace. Then, on March 4, the nation’s crisis would become Lincoln’s problem.” (Who would have thought that we could ever stomach a president more concerned about his own legacy and personal comfort than the fate of the nation during a potentially existential crisis?)

Of all the “paths not taken” while the tension over Fort Sumter escalated, it was the lame-duck president’s indifference that seems to have sealed the fate of the country. When asked recently what might have been done to avoid civil war, Erik Larson reluctantly proffered that it was the “inaction” of President James Buchanan that left the events swirling around Fort Sumter in the hands of the demagogues.*

One of these demagogues is Edmund Ruffin, described on Larson’s book jacket as “a vain and bloodthirsty radical who stirs secessionist ardor at every opportunity.” Ruffin, as Larson writes, “worked obsessively to promote secession. He traveled the countryside preaching disunion and took every opportunity to rage at Northern ‘tyranny,’ arguing that the South was even more oppressed by the North than the early colonists had been by the British before the American Revolution.”

Within his own state, which only chose secession after the attack on Fort Sumter, Ruffin was “all but ignored by his fellow Virginians, who dismissed him as a hate-mongering fanatic.” In perhaps the biggest “what if?” in this story, had Virginia and the other post-Fort Sumter secessions of North Carolina, Arkansas, and Tennessee, decided to stay in the Union, any subsequent war would have left the Confederacy with a completely diminished capacity to defend itself. Actually, Larson offers that, had Virginia not seceded, the states that already had left might have been prodded to withdraw their secession decision and return to the Union.

As it turned out, the eleven-state-strong Confederacy, whose army was led by Virginian Robert E. Lee, was able to hold out during four bloody years of human carnage and despair.

It is also important to note that Lee has often been considered one of the ablest leaders during the Civil War and it has been reported that Lincoln asked Lee to command Union forces. Eight days after Fort Sumter was attacked, and three days after Virginia seceded; Robert E. Lee resigned from the US Army. “If Virginia stands by the old Union,” Lee said, “so will I. But if she secedes (though I do not believe in secession as a constitutional right, nor that there is sufficient cause for revolution) then I will follow my native State with my sword, and, if need be, with my life.”**

Perhaps the most gripping part of this remarkable history follows Major Robert Anderson, the commanding officer at Fort Sumter. As a former slave-owner, Anderson was sympathetic to the South but he remained loyal to the Union and the US Army. With little guidance from Buchanan’s Washington, he understood that surrendering the fort without a fight would signal that other federal forts throughout the South could be claimed as well. Again, the decision to defend the fort was influenced by a Southerner’s sense of honor.

Anderson also knew, because he could see it happening, that the massive delay in sending reinforcements to Fort Sumter gave the newly organized Confederacy the time they needed to prepare to bombard the fort or prevent any effort by the North from entering the harbor.

It appears that decisive federal action following South Carolina’s secession could have sent a strong signal to the other states that were considering secession. Larson offers a great deal of evidence that President-elect Lincoln would have taken these more decisive steps.

In addition to these larger moments that could have gone another way, Erik Larson’s The Demon of Unrest is replete with a great number of minor events and decisions, often made with nefarious intent and guided by personal ambition, that put the nation on the path to war.

While it is impossible to determine which of the moments of our own day might take on such a sinister sheen, we should take comfort in knowing that sometimes the small stuff matters; that any energy we put toward understanding our own world and its problems more clearly can make a difference.

In an age when many people are simply checking out, Erik Larson, while entertaining us with this great story, is also encouraging us all to pay a little more attention.

*https://www.npr.org/programs/fresh-air/archive

**From R.E. Lee: A Biography by Charles Anderson, 1936