The open ocean is a strange place, always shifting, always changing. It begins where coastal waters end, and it covers most of the planet—300 million cubic miles of it. The scientific name for the open ocean is “pelagic,” which is Greek for “open sea.”

This vast area is divided into zones based on proximity to land and also ocean depth. The coastal pelagic zone is the mostly sunlit area above the continental shelf that descends to a depth of around 650 feet.

The ocean pelagic begins where the continental shelf ends. It helps to envision the ocean as a column of water—like the contents of a gigantic pyrex measuring cup, but instead of a measuring cup’s ounces and milliliters, this imaginary container is measured in zones: from top to bottom, this column is divided into the epipelagic, mesopelagic, bathypelagic, abyssopelagic, and hadopelagic. At the bottom, buried in the mud, lies the benthic zone. There are echoes of Dante’s Inferno and the ancient Greek god of the dead in the names for the deepest depths, and that’s appropriate, because the creatures that have evolved to live there dwell in perpetual darkness.

Beneath the column of water are canyons that plunge to depths of as much as three miles, and mountain ranges and seamounts that lie just below the surface. It’s a complicated geography that affects everything about the column of water above it, including the things that live in it.

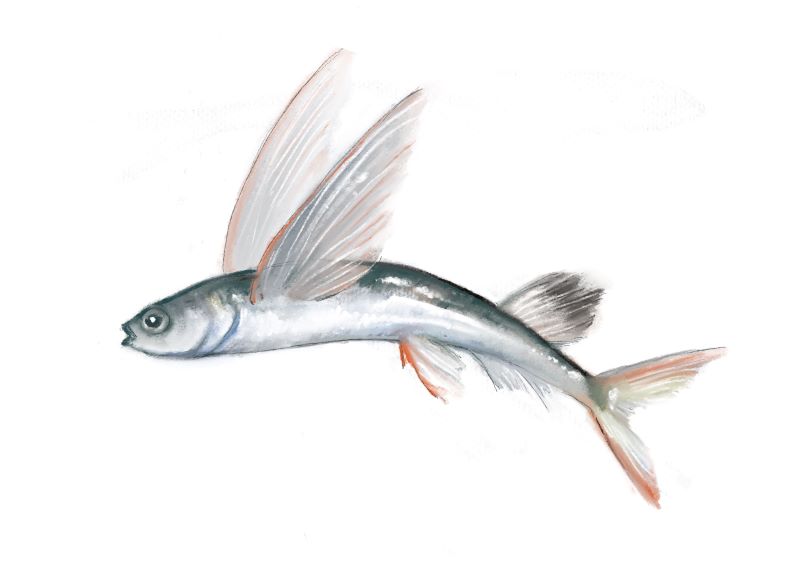

The term “pelagic species” usually refers to the animals that live in the sunlit upper layers of the open ocean, but unlike the neat, contained space of a measuring cup, none of these zones have fixed borders. Everything here is affected by currents, waves, wind, salinity, pressure, temperature, nutrients, hydrology and the underlying geology. Some species travel between the zones to feed or to hide from predators. Some live their whole lives in darkness. Others float on the surface. The sperm whale must come to the surface to breathe, but it can also dive to depths of more than 3,000 feet in pursuit of squid and other prey—a change in pressure that would kill human divers without the mechanical aid of a decompression chamber. Seabirds like albatrosses and stormy petrels spend their lives almost entirely at sea, traveling thousands of miles across the ocean, coming to land only to breed in the spring. Sightings on shore are rare, but out where the continental shelf drops away birds like these gather to forage. There are endemic species out there too, like Scripp’s murrelet, Synthliboramphus scrippsi, a small member of the auk family with a population estimated at around just 15,000.

The open ocean is an almost unimaginably vast place, but some parts of it are more densely populated than others, and the coastal waters along the California coast at the edge of the continental shelf are home to an amazingly diverse range of creatures.

In the spring and early summer, cold water upwelling brings organisms from the deep to surface along the edge of the shelf, providing food for everything from tiny anchovies and planktonic sea gooseberries, to ocean giants, like white sharks, sunfish, and whales.

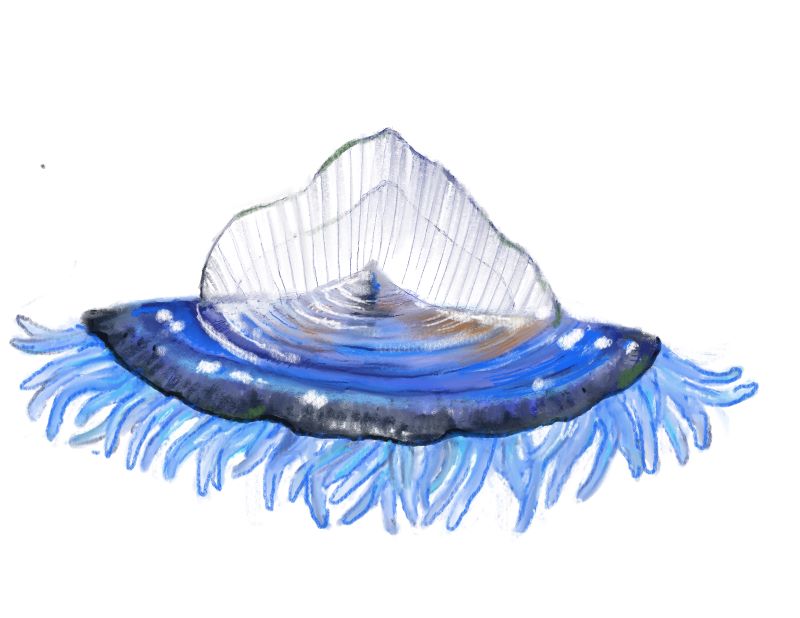

By-the-wind sailors, Velella velella, tiny colonies of cnidarian siphonophores that go where the wind drives them, made headlines in Los Angeles earlier this spring when huge numbers washed up on local beaches. In other years no trace of these long distance mariners is seen from shore, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t out there, together with the things they eat and the things that prey on them.

At Topanga State Beach, the sea floor slopes away gently towards the edge of the continental shelf. Up the coast at the Point Dume State Conservation Area, the drop off is much more abrupt and closer to shore. Just off the end of the eponymous point, a submarine canyon descends to a depth of a thousand feet. That nearshore drop-off is one of the reasons Point Dume is an ideal place to look for migrating gray whales, migratory seabirds, and year-round residents species like bottlenose dolphins, sea lions, and white sharks. It’s an eat or be eaten world out there, and anything that isn’t eaten usually ends up on the bottom—food for benthic organisms—but some of the smaller things that live on or near the surface end up on the beach, carried by wind, wave, and current. Beachcombers have a good chance of encountering strange emissaries from the open ocean at this time of year: jellies, salps, pyrosomes, and even whole fish, cast ashore by spring tides.

Salps and pyrosomes are among the most abundant zooplankton on the beach in early summer. They are often mistaken for jellies. These semi-transparent sea creatures are planktonic tunicates that belong to the phylum Urochordata, which means they have a rudimentary skeletal rod and a nerve cord, making them more closely related to vertebrates—including humans—than they are to true jellies. Some tunicates live life anchored to rocks, but salps and pyrosomes are free-floating.

Pyrosomes (Pyrosoma atlanticum) are tube-shaped colonies of hundreds, thousands, or sometimes tens of thousands of tiny zooids. Salps have two life phases: one as a solitary individual, the other as part of a chain of identical cloned animals produced by the solitary phase. Surprisingly little is known about this family, so little that it’s challenging to pin down which species wash up on local beaches. However, a recent study suggests that salps may be instrumental in sequestering carbon on a large scale—an impressive superpower for a humble tunicate.

Both types of tunicate pump water through their tube-like bodies and filter out smaller plankton, but despite being jet powered, they are at the mercy of the currents and tides, which can result in large numbers becoming stranded. When beachcombers encounter salps or pyrosomes on the sand they are almost always dead and often incomplete. The salps resemble puddles of aspic or shards of glass shaped like pen nibs. The pyrosomes are tougher and tend to remain intact, but these strange, pinkish creatures dry out incredibly fast, shrinking as they dehydrate.

Velella velella, the by-the-wind-sailor, lives up to its name. Its stiff, transparent sail enables it to travel across the surface of the water, but it doesn’t have the ability to steer. This species often makes headlines whenever large numbers strand themselves on the beach. By the time they wash ashore, sometimes by the thousands, they are usually already dead, battered by the shore break, and far from home.

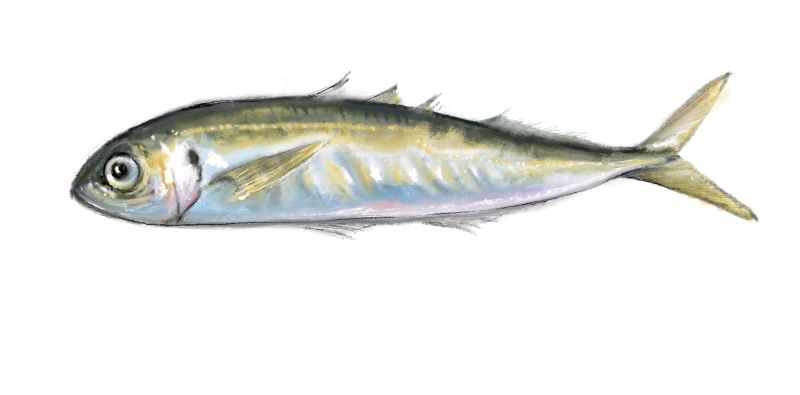

Although they are stronger swimmers than creatures like salps and jellies, small fish can also be caught by the current and cast onto the shore. Sardines, anchovies, herring and mackerel are pelagic species that are part of California’s multibillion-dollar pelagic fisheries, and are also critically important food species for a huge number of animals in the open ocean, including larger fishes, seabirds, and marine mammals.

The type of sardines most of us are familiar with are small—less than six inches, but the California sardine can grow to be up to 16 inches long. It is an adaptable species, found in the open ocean and near shore, but it is classed as a pelagic fish.

The demand for commercial canned sardines peaked in the 1950s, but California sardines continued to be heavily fished until 2015, when the commercial fishery was closed because the sardine population was being pushed to extinction. This fish current has had a chance to recover from overfishing, but it faces other environmental pressures, including climate change.

Like sardines, northern anchovies have benefitted from a decline in popularity among human predators, mostly appearing today as a component of Caesar salad. There is still a commercial anchovy fishery in California, but it is a small one—in 2022, commercial landings of northern anchovy totaled 3.5 million pounds and were valued at $680,000, according to the NOAA Fisheries. Most of the catch meets with the inglorious fate of being used for bait or ground up for fish meal, but the relatively low demand means this fish isn’t threatened with overfishing, at least, not at the moment. That’s good news for the numerous species that depend on this fish as a food source, including a wide range of seabirds.

Life has been topsy-turvy for the mackerel. A population crash in the 1980s, “led to rapid expansion in the 1990s of the market squid (Doryteuthis opalescens) and Pacific sardine (Sardinops sagax) fisheries in Southern California, the CDFW reports. Today the mackerel fishery is around 2,000 tons a year—two percent of the total amount of fish caught commercially off California.

There’s a pattern here, a cycle tied to food resources, weather, ocean temperature and usually to human activities. When something goes wrong with the life cycle of these small fishes, everything that depends on them is also at risk. We know about events like the population crash of sardines because of how it impacts human needs—from food to employment, but it also impacts the needs of the wildlife that depend on species like the sardine for survival. The ocean is a big place, but everything here is interconnected, often in ways humans are only just beginning to understand.

For the beachcomber, the things left behind by the tide can be puzzling: transparent blobs of salps resemble melting ice, or aspic, the sails of by-the-wind-sailors that look like whorled fragments of plastic, the transparent bells of medusa jellies, tiny fish with impossibly big eyes, and the bones of larger vertebrates. These emissaries from the open ocean are usually already dead when they wash ashore, but the message they bring is that the ocean is full of strange and wonderful things most land-dwellers know little about.