“If you want to be a writer, you must do two things above all others: read a lot and write a lot. There’s no way around these two things that I’m aware of, no shortcut.”

—Stephen King, from On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft

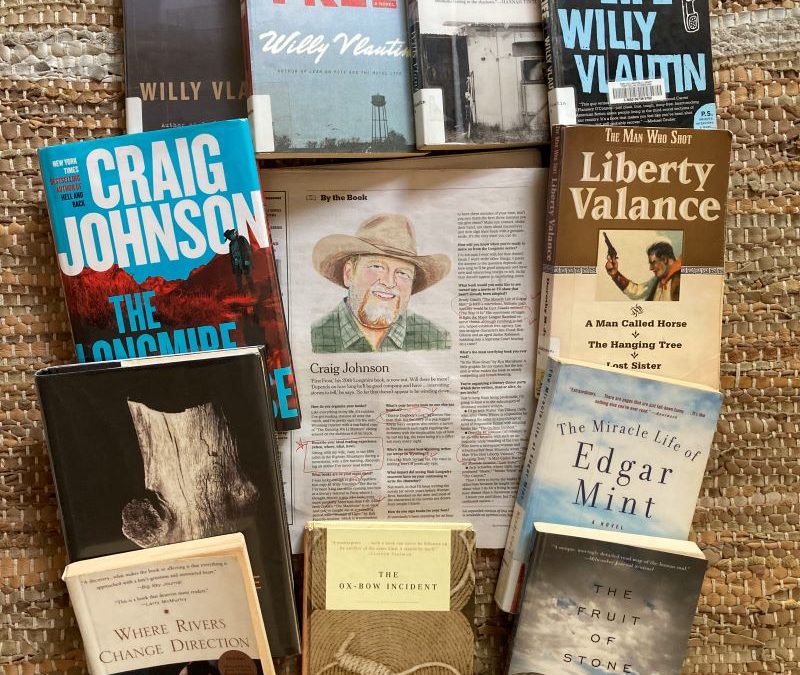

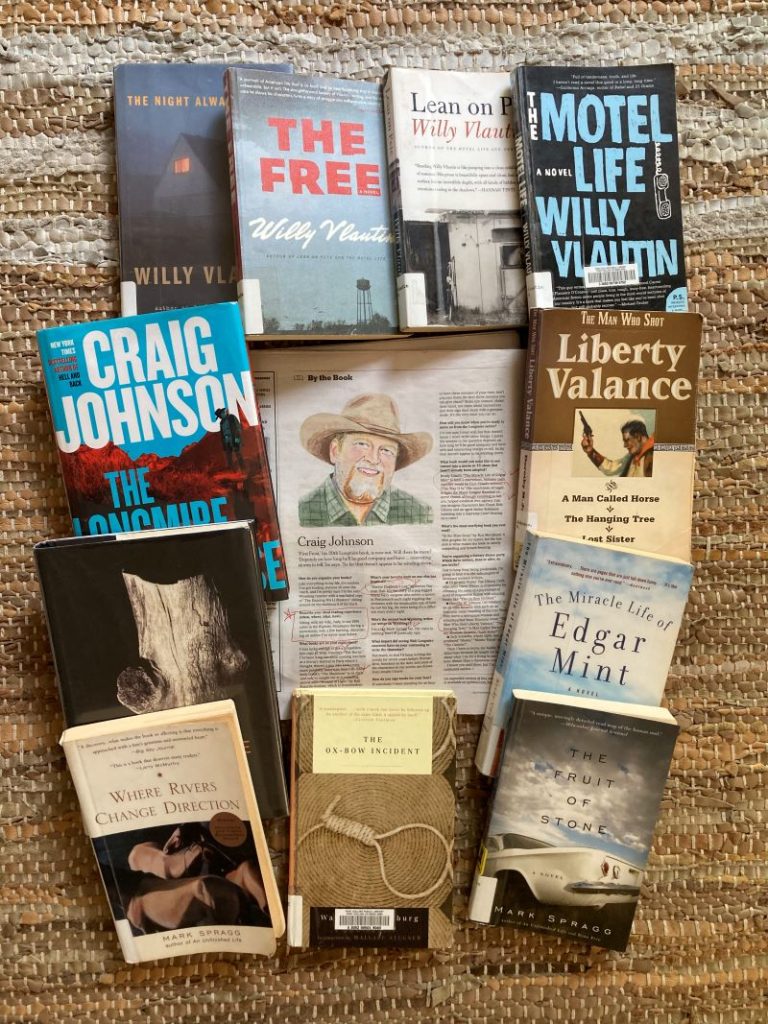

A recent feature in the New York Times Sunday Book Review focused upon an interview with Craig Johnson, who has just published the twentieth volume in a series exploring the tribulations and adventures of Absaroka County Wyoming Sheriff Walt Longmire.

I am a long-standing fan of Johnson and his fictional Sheriff Longmire, as I have written previously:

Set in Northern Wyoming, Craig Johnson’s series of books about Sheriff Walt Longmire introduces readers to a remote part of the country where the dramatic upheavals of the natural world co-exist with the violent tendencies of mankind. Longmire is a widower and Vietnam vet, which is the short way of saying that he is often morose and reflective. It is only when he is solving crimes that he finds himself energized; almost always in defense of the underdogs.*

So popular are these wonderful modern Western tales that on July 18-21, 2024, an annual celebration of the author and his creation will take the form of “Longmire Days” in the city of Buffalo, Wyoming – population 5000 or so—near Johnson’s ranch and home in Ucross, Wyoming—population 25.

In the NYT Book Review interview, Johnson speaks of the books that have inspired him. It occurred to me that the books that inspire an author I adore might be books I would enjoy myself. It took about 30 minutes using Colorado’s Prospector library-sharing service to order up a wonderful collection of old books. Many of these books had familiar names because movies have been made from them, but I had not read them.

It is almost a given to say that good writers are voracious readers; not just because they spend the time with letters, but because writers read the books that explore the ideas that, when reshuffled, fertilize the formation of new ones.

When asked which writers he would invite to a “literary dinner party,” Craig Johnson first mentions Walter Van Tilburg Clark, author of The Ox-Bow Incident (1940), set in a frontier town in 1885. After whiskey, poker, and a barroom fight, Clark’s groundbreaking novel moves well beyond the western trope of good guys and bad guys, white hat and black. A young man races into town upon a galloping and frothing horse with word that a popular ranch foreman has been shot and killed and that a great number of cattle have been stolen. With the town sheriff away, there is an immediate call for justice. Unfortunately, as the mob/posse forms, there is a bit of confusion over exactly what “justice” means.

While a posse has the imprimatur of law enforcement, a mob does not. Throughout much of this story, it is not clear whether the twenty-eight men heading out in pursuit of the rustlers have been properly deputized, and therefore acting on behalf of, and in deference to, the law. Indeed, the dynamic that evolves on the trail includes the tangled effort to justify what they are likely up to.

Clark’s behavioral exploration within this quickly organized group and conversations pondering the nature of justice has The Ox-Bow Incident mimicking the diverse thinking among ancient Greek and Roman philosophers. Although, in this case, these philosophical conversations lead to real-life consequences for the members of the mob/posse and particularly, the three men they later encounter.

As evidence mounts that they have found the rustlers/murderers, some of the men want to hang them right there while others say the right thing to do is take them back to town for a trial. Much of the drama here takes place in the head of the narrator as he engages with those leading the mob/posse—by virtue of personality and reputation, not necessarily the law—and those being strung along and eventually, those that are strung up. What follows is an acute examination of the human condition; where many of the humans are susceptible to manipulation despite their growing unease at the prospect of violence.

The parallels to Craig Johnson’s Walt Longmire series and The Ox-Bow Incident are unmistakable.

Other authors invited to his dinner party include Dorothy M. Johnson and Jack Schaefer, two of the greatest Western writers of the twentieth century. Many of their stories were made into motion pictures with familiar names like The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (Johnson) and Shane (Schaefer). While these films are classics, some have observed that they fail to live up to the rich social commentary found within the books.

Speaking of film, Johnson reports that the book he would “most like to see made into a movie or TV show,” is The Miracle Life of Edgar Mint (2001), by Brady Udall. I haven’t gotten around to this one yet but it opens with:

“If I could tell only one thing about my life it would be this: when I was seven years old the mailman ran over my head. As formative events go, nothing else comes close; my careening, zigzag existence, my wounded brain and faith in God, my collisions with joy and affliction, all of it has come, in one way or another, out of that moment on a summer morning when the left rear tire of a United States postal jeep ground my tiny head into the hot gravel of the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation.”

I’ll let you know how this one turns out.

Johnson’s favorite book “no one has ever heard of” is Doctor Dogbody’s Leg (1940), by James Norman Hall. “It’s the story of a peg-legged Royal Navy surgeon,” Johnson reports, “who enters a tavern in Portsmouth each night regaling the denizens with the implausible tale of how he lost his leg, the twist being it’s a different story every night.”

Seeing as Johnson believes that “no one has ever heard” of this one, I am not surprised that there appear to be only two copies available in the entire state of Colorado, one at the Denver Public Library and the other at the library of the United States Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs. Hmmm? I am fifth in line with four others having requested a “hold” on this 84 year-old book; so it appears that Craig Johnson’s NYT interview has generated some interest.

When asked about the books presently on his nightstand, Johnson mentions a pre-publication copy of the latest novel by Willy Vlautin, The Horse, which will be available July 30, 2024. Two of the books I have received are Vlautin’s The Motel Life (1999) and Lean on Pete (2010) and both are literary treasures; like those wonderful gems we stumble upon from time to time without much effort at all. Both of these wonderfully written stories feature people trying to do the right thing while desperate circumstances get in the way; gut-wrenching and heartwarming in equal measure.

Set in and around the modern rural Rocky Mountain West, the deep social and economic problems explored in Vlautin’s books offer hints to the political frustrations experienced by large numbers of Americans today. While these real-life problems have led many to become supporters of a populist demagogue, understanding the origins of their complaints seems a prudent move if we are to understand what so starkly divides us. Craig Johnson’s Longmire stories and at least two of the novels of Willy Vlautin go a long way to doing just that.

Assuming we all know where Craig Johnson stands in this matter, the interviewer then asks, “Who’s the second-best Wyoming writer?” Johnson names Mark Spragg. “His voice is nothing short of poetically epic,” he says. After reading Spragg’s The Fruit of Stone (2002), I understand what he means. While not rich with the intimate social observations of Johnson’s other loves, The Fruit of Stone is beautifully drawn with vividly colorful descriptions of the landscape that animate the personalities of its prime characters. Spragg has written a number of other novels and a wonderful collection of autobiographical essays, Where Rivers Change Direction (1999). When Spragg writes about rural Wyoming, he is writing from personal experience as evidenced in essay titles such as “In Praise of Horses” and “A Boy’s Work.”

Luckily for me, Buffalo, Wyoming is only five hours up the road.

*Books & Such, Some Friends of Mine, Topanga New Times, June 4,2021