We have been reminded lately— on more than one occasion—that the protections afforded by the US Constitution’s system of checks and balances are vulnerable to manipulation by bad actors. This is perhaps most threatening when the singular chief executive, the president of the United States, uses the position to violate all norms of established behavior while wielding a measure of control over the other branches of government.

So, what happens when the US president shows little respect for the guardrails that attempt to define and limit the powers of the executive branch?

For example, what happens when the president encourages his supporters to use violence against political opponents? Or, what happens when a president arrests and imprisons critics? What happens when a president uses his power to spy on US citizens? What happens when a president declares himself to be above the law?

And, what happens when the president holds sway over the Supreme Court while behaving badly?

Finally, in claiming these extra-Constitutional powers, what happens when a US president moves forward with the goal of bolstering white supremacy? What happens when a president justifies his actions by claiming that some people in this country are less than human?

As frighteningly familiar as this may sound, it appears that we can take some small comfort in learning that all of these things have happened long before the current crisis and, in the end, these very real threats to our democracy’s constitutional order were largely overcome.

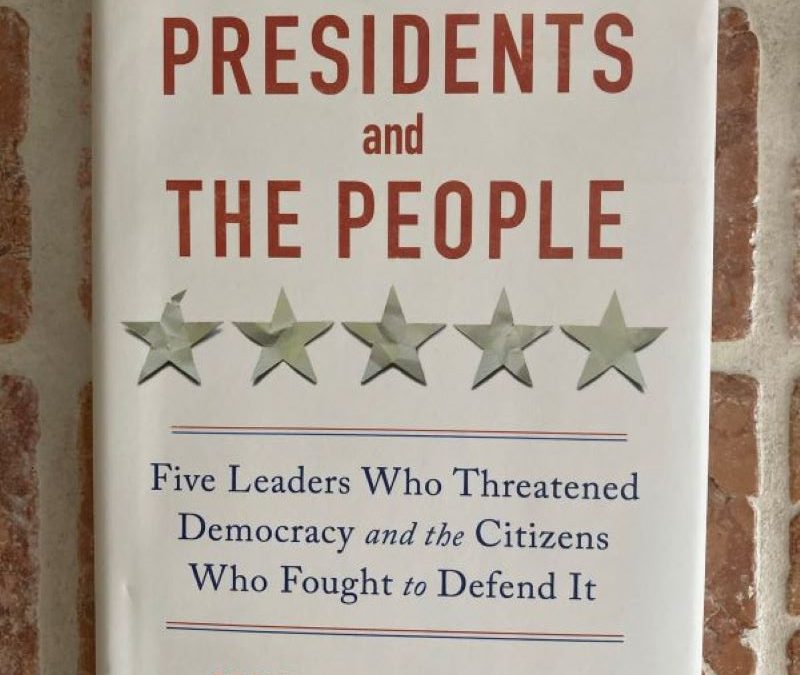

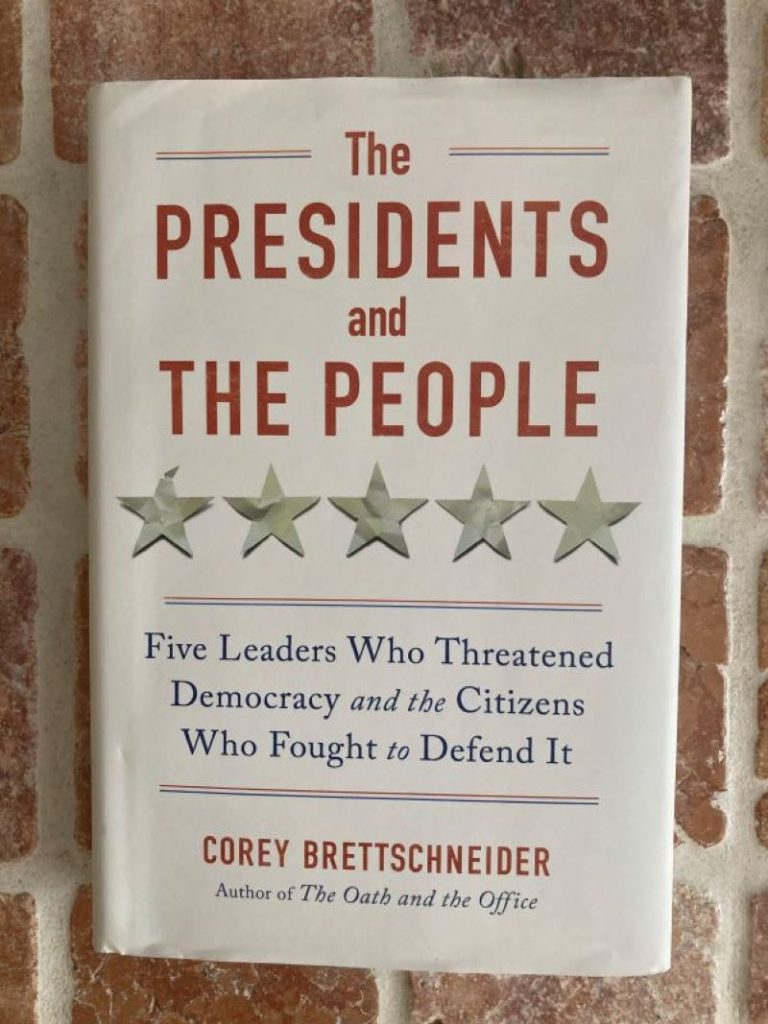

I think of this now after reading The Presidents and the People: Five Leaders Who Threatened Democracy and the Citizens Who Fought to Defend It (2024) by constitutional law and politics professor Corey Brettschneider.

While this book is about five presidents who behaved badly, it is much more about the manner in which American citizens exercised their ultimate sovereignty—as established in a Constitution which begins “We the People”—to hold these presidents accountable.

Brettschneider’s earliest example vividly illustrates that when our democratic principles are threatened, citizens need not necessarily accept the decisions and verdicts of those behaving badly.

In the first years of the nation, there was a great deal of speculation regarding the solvency of a country founded with such lofty principles as liberty and equality. As a credit to a US Constitution ratified in 1788, the 1790s saw a rapid increase in the number of newspapers being published in the United States. Long before news outlets began claiming their objectivity, however, newspapers of this era were proudly political, mimicking the nascent development of political parties during George Washington’s eight years as president.

As John Adams (1797-1801) became president, he and Thomas Jefferson were the leaders of two very different visions for the country’s future; centering on the fundamental powers and privileges of the presidency. As it turned out, Adams and his fellow Federalists that controlled the Congress were not very fond of being ridiculed in the press, and with the thinnest of skin, Adams signed the Alien and Sedition Acts in 1798. These measures severely restricted the people’s right to criticize “the president, the government generally, or congressmen.” In a clear violation of the First Amendment, several publishers of Democratic-Republican newspapers were arrested for criticizing Adams.

Those charged used their trials to widely publicize the unconstitutionality of the laws restricting a free press. In one case, a defendant attempted to subpoena the president himself. Unfortunately, the federal judge in the case had been an open supporter of the Alien and Sedition Acts so the subpoena was denied.

Newspaper editors were found guilty, fined, and jailed; but then used their voices to decry the injustice. Citizens protested the laws across the country. The states of Kentucky and Virginia declared the laws unconstitutional and threatened to secede if they were not repealed.

This publicity made the Alien and Sedition Acts a critical issue in the 1800 presidential election. Jefferson and the Democratic-Republicans won, beginning a twenty-four-year period of rule for their party. In another “it’s happened before” moment, the 1800 race was very close and Adams tried to sew chaos. He attempted “discard and refuse to certify electoral votes on a case-by-case basis,” Brettschneider writes, “a proposal similar to those floated by Ted Cruz and others regarding certifying the 2020 electoral votes…” As in 2020, the scheme failed.

In the end, these Alien and Sedition Acts cases “revealed that when the judiciary failed to protect constitutional rights, citizens could step in.” Brettschneider adds that “Jefferson later argued that if courts alone were trusted as the sole interpreters of constitutional rights, they could mold these rights like ‘wax’ into whatever they wished.” Does any of this sound familiar?

In four other dramatic instances, Brettschneider offers chilling examples of presidents abusing their power, often in cahoots with a politically influenced Supreme Court. In each case, citizens stepped in to shape events. Some of these patriots have become household names such as Frederick Douglass, Ida B. Wells, W.E.B. Du Bois, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Daniel Ellsberg.

Brettschneider features many others who may not be so familiar: lawyer and editor Thomas Cooper who was one of a handful that challenged John Adams; William Trotter, who used his wealth and influence to support the rights of working-class Blacks during the depths of Jim Crow; Sadie Alexander, a lawyer and the first African American woman to receive a PhD. in economics in 1921, who fought for civil rights throughout much of the twentieth century; and Walter White, who led the NAACP through the formative years of the modern civil rights movement.

The Civil War offers stark contrast among a pair of presidents who defended the Constitution and a pair that clearly did not. On the eve of the Civil War, James Buchanan (1857-1861) “attempted to expand slavery nationally.” This effort was bolstered by the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision of 1857, which claimed that “negroes” at the founding were “so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit.”

President Abraham Lincoln (1861-1865) entered the White House in full defense of protecting slavery where it existed. By 1863, however, he issued the Emancipation Proclamation which made ending slavery the clear goal of the war. This change of heart was due in large part to Frederick Douglass and others who impressed upon Lincoln the idea that slavery was incompatible with American legal and moral principles.

After Lincoln’s assassination Andrew Johnson (1865-1869) “sought to make the end of slavery brought about by the Thirteenth Amendment consistent with a belief in white supremacy.” Douglass continued to fight for Black equality and then encouraged Ulysses S. Grant (1869-1867) to assert the powers of the federal government to ensure that the states of the former Confederacy honored the dramatic changes to the US Constitution. This brief period of Reconstruction was witness to the emergence of efforts to promote the economic, social, and political rights of the formerly enslaved.

Unfortunately, during the decades that followed, “a series of Supreme Court decisions narrowed the meaning of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments” which had been intended to provide “equal protection” before the law and ensure voting rights for African Americans. In Plessy v. Ferguson, 1896, the Court established the doctrine of “separate but equal” which ushered in decades of Jim Crow segregation.

Despite the setback, the struggle for civil rights continued. At the turn of the century, Ida B. Wells bravely documented the manner in which Southern Blacks were being terrorized into submission and kept away from the ballot box. William Monroe Trotter, a wealthy Boston Black man who founded the Guardian newspaper, encouraged working-class Black people to stand up for their rights in the face of Northern-style de facto segregation and discrimination.

In 1909, W.E.B. Du Bois and others organized the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) which became a critical tool during the formative years of the modern civil rights movement.

With segregation firmly in place, however, Woodrow Wilson (1913-1921) “tried to build a national racial hierarchy.” Dramatically flaunting his racism, Wilson hosted a screening of the film “The Birth of a Nation.” which glorified the Ku Klux Klan and glamorized the failed efforts of the Confederacy during the Civil War (it was during this era that the myth of “The Lost Cause” motivated the erection of statues and monuments that completely refashioned the motivations behind the greatest rebellion in American history).

Denied access to positions of political power, African Americans worked on their own to defend the rights guaranteed in the Constitution. Black newspapers such as the Pittsburgh Courier, the Baltimore Afro-American, and the Chicago Defender reached a national audience and spread the seeds of the civil rights movement that would germinate only after the country stood fast against fascism during World War II.

Brettschneider’s case for citizen defenders of the Constitution reaches fruition during the 1950s and 1960s. Charles Hamilton Houston, Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund almost single-handedly impressed upon the Supreme Court that segregation was not only unconstitutional, it was an affront to the moral crusade the country had waged against fascism. Perhaps more than any other decision, Brown v. Board of Education, 1954 —which overturned Plessy’s “separate but equal doctrine” —demonstrated both the fallibility of the Court and, more importantly, the power of citizens to set things right.

The active movement that followed is replete with citizen actors challenging the government to honor the promise of the Civil War amendments; Rosa Parks, John Lewis, Martin Luther King, Jr., the Little Rock Nine, college students, and so many more.

The crowning achievements of the civil rights movement were the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. However, Lyndon Johnson signed these momentous bills into law only after embracing the appeals from those who were leading the movement.

Shortly after the violent crackdown against peaceful protesters in Selma, Alabama in 1965, President Lyndon Johnson gave a speech to a joint session of the US Congress and to the American people. “We Shall Overcome” he said. By embracing the language of the protesters, LBJ essentially joined those in the streets calling for passage of the voting rights bill. One hundred years after the American Civil War, the federal government finally stood firmly behind the constitutional rights of African Americans because the citizens of America finally screamed loud enough to be heard.

And then Vietnam rocked the nation.

In its wake, Richard Nixon (1969-1974) claimed his well-known crimes were legal; that it was proper for the president to use the tools of government to target and discredit critics and political opponents. In this case, Brettschneider identifies the roots of our current troubles beginning with President Gerald Ford’s pardon of Richard Nixon. While avoiding the disgrace of putting a former president on trial, the country missed the chance to thoroughly expose Nixon’s crimes and clarify the scope and limits of presidential power.

So, as we deal with similar claims today, that a president is above the law, Brettschneider reminds us that “citizens” throughout our history have “invoked their own right to read the Constitution by and for the people, and used their interpretation to hold presidents to account.”

And, as we deal with a Supreme Court which threatens to undo much of the progress we have made as a multi-racial democracy, Brettschneider admits that “Our current moment is… marked by profound antidemocratic threats.” He adds however that “the examples provided throughout [his] book make clear that while our democratic Constitution is vulnerable, committed citizens can save it.”

Don’t forget, he closes, “history is replete with examples of the court abusing its supposed role as defenders of constitutional rights.” Indeed, “When presidents push America through the guardrails of the Constitution, the court often goes along with it.”

There is nothing explicitly written in the US Constitution granting the Supreme Court of the United States the power to determine what the words of the Constitution mean; that when disputes are settled by the Court, this is considered to be the final say or, the last word. It was actually a Supreme Court decision—Marbury v. Madison, 1803—that the Court claimed this power for itself.

Corey Brettschneider eloquently offers that citizens have often asserted their right to interpret the Constitution; that in a government established by “We the People” it is the people who shall have the last word.