Imagine a society where new technologies allow information to be sent across continents and oceans in a matter of seconds. Imagine a society where the means of sending that information is in the hands of only a few very wealthy individuals. Imagine, too, that these individuals have their eyes more keenly focused upon profit rather than the truth. Imagine, finally, that the people of this society constitute a massive audience all too willing to pay for stories that entertain more than they inform; a people susceptible to propaganda and misinformation that, for many of them, shapes their view of the world and their responsibilities to it.

It was 1898 and the “yellow” press clamored for war with Spain. The American battleship Maine, sent to Cuba to protect American interests there as Cubans fought for independence, had mysteriously imploded/exploded in Havana Harbor. William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal and Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World inflamed public opinion against Spain although there was no evidence that the Spanish were responsible for the Maine disaster in which 260 Americans were killed. (Yellow journalism is “the use of lurid features and sensationalized news in newspaper publishing to attract readers and increase circulation.”)*

Another justification for the war was the reported Spanish atrocities committed against Cubans. In cutthroat competition with Pulitzer, Hearst famously told an illustrator, “You furnish the pictures, and I’ll furnish the war.”

In what was described as a “splendid little war,” the US easily defeated the fading empire. As a result of the Spanish-American War, fueled by a media environment hungry for profit with an audience salivating for gore, the United States acquired Cuba and Puerto Rico in the Caribbean, and the former Spanish colonies of the Philippines and Guam in the Pacific. With the last of the European powers expelled, the US exercised hegemony over the entire Western hemisphere and it extended its military presence into the Pacific and Southeast Asia. Within a few short months, after a war promoted by newspapers, the United States had become a world power.

I share this so you might grasp the power of New York City’s newspapers at the turn of the twentieth century as this is the setting for Battle of Ink and Ice: A Sensational Story of News Barons, North Pole Explorers, and the Making of Modern Media (2023) by Darrell Hartman. With no radio, no television, and certainly no internet, the power of newspapers at this time cannot be overstated.

Making it possible, just as today, was new technology. In this case, the dots and dashes of Morse Code that, by the time Hartman’s primary story takes place in 1909, had thoroughly revolutionized the nature of global human communication. The proliferation of the telegraph in the second half of the nineteenth century may be the single largest leap ever taken in the establishment of a global sense of humanity. Prior to the telegraph, information and news traveled only at the speed of a horse or a ship.

A third element to this fascinating book is world geography. By the late nineteenth century many of the mysteries of the surface of the earth had been explored and mapped; further enhancing the idea of a global humanity. It is hard to imagine living at a time when the contours of the world in which we live were largely unmapped, a reality for well over a million years of human existence.

In the first decade of the twentieth century, one of those remaining unknown places was the North Pole. Explorers, largely financed by New York newspapers, raced to discover that place on earth where taking a step in any direction meant taking a step to the south; a place where there is no north, or east, or west. That place where taking a step in one direction would be midnight and in the opposite direction, noon. For, it is at the North Pole that the lines of longitude converge upon a single point.

Battle of Ink and Ice tells the story of this wildly fascinating competition while exploring the evolution of American journalism.

Arctic explorer Robert Peary returned to civilization in September of 1909 claiming to have reached the North Pole the previous April only to discover that, a week earlier, Frederick Cook had claimed to have reached the North Pole in April of 1908. Cook’s return was delayed by the breakup of sea ice, “forcing his three-man team to survive a second Arctic winter on their own.”

In a monumental coincidence, The New York Herald—which had financed Cook’s expedition for the exclusive rights to his story—reported in a bold headline on September 2, 1909 that:

“THE NORTH POLE IS DISCOVERED BY DR. FREDERICK COOK WHO CABLES TO THE HERALD AN EXCLUSIVE ACCOUNT OF HOW HE SET THE AMERICAN FLAG ON THE WORLD’S TOP”

Five days later, The New York Times—which had financed Peary’s expedition for the exclusive rights to his story—published a headline on September 7 that read:

“PEARY DISCOVERS THE NORTH POLE AFTER EIGHT TRIALS IN 23 YEARS”

On the same Times front page it is reported that Cook cabled, “Glad Peary did it. Two records are better than one, and the work over a more easterly route has added value.”**

Each man was compelled to provide evidence of his claim. Using “state-of-the-art thermometers, barometers, sextants, compasses, chronometers, and pedometers [Cook claimed he] recorded his progress diligently on the drifting sea ice.” As it turns out, though, Cook conveniently had left all of his materials in Greenland in the care of a friend. Peary quickly denounced Cook as a fraud and the ensuing newspaper war riveted much of the Western world.

Fully understanding this development requires understanding the manner in which newspapers were changing. Echoing elements of our current media landscape, while Hearst and Pulitzer engaged in the bombastic and exaggerated reporting that titillated the masses with stories of sex, crime, scandal, and humor through the 1890s, they often paid little respect to the truth. When challenged, as Hartman writes, “The authors of these elaborate and entertaining lies described them as satire and professed to be surprised when they succeeded in fooling thousands.” He adds that “As standards of accuracy slipped during the Hearst-Pulitzer circulation wars, blatant falsehoods became a regular feature of powerful newspapers…”

“The problem,” Hartman writes, “was that accurate and important reporting appeared alongside all manner of tall tales, making it very difficult to tell the two apart.” One of Hearst’s Journal reporters was called out for his mendacious reporting from the Philippines during the Spanish-American War. He “later justified his creative liberties on the grounds that they were so widespread: ‘It was a shameless bit of faking, but all the newspapers were doing it.’”

It makes it more difficult to challenge obvious falsehoods when the falsehoods become wildly popular. “By 1900,” Hartman reports, “94 percent of American households read the newspaper, compared with just one in three” in the 1870s. “Publishers around the country had come to rely on New York City’s wire services and daily journals for their national and foreign news, special features, and syndicated comic strips.” Just as we talk today of the effects of spending too much time in front of screens, “the public’s appetite for [newspapers at the turn of twentieth century] seemed insatiable.” And much that was printed was simply not true.

As I see it today, a similar dynamic seems to be playing a rather prominent role within our political discourse. For instance, it has been repeatedly reported that one of the 2024 candidates for president has openly claimed that if a lie is told often enough, it acquires a patina of truth. Which makes me wonder if our own divisive time is not an aberration, but another reflection of a basic truth of human nature: we don’t mind being lied to if it makes us feel good.

By 1909, James Bennett Jr.’s New York Herald, by far the most widely read New York paper, tended to appeal to a more refined and educated clientele where the appeal for “yellow” news was tempered. If you are looking for some hope in all this, when Adolph Ochs purchased the struggling New York Times in 1896 for $75,000 of borrowed money, he believed that, as Darrell Hartman writes, the paper “stood for many of the values that he cherished and strove to embody.”

While Ochs certainly had his own political biases, he attempted something new. He believed that there was a genuine market for objective news reporting and a commitment to the facts, and he was right. Despite the continued existence of the “yellow press”—think National Enquirer —it seems that most news outlets today, whether accurate or not, present themselves as bastions of objectivity, or, “fair and balanced” as you may have once heard.

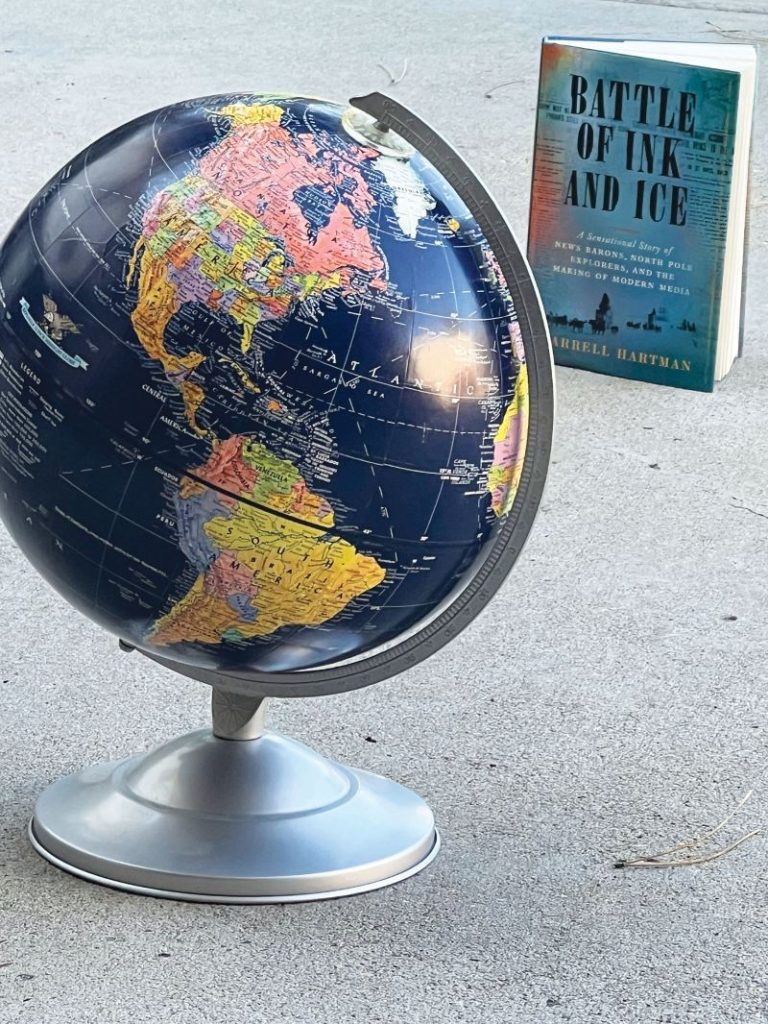

Darrell Hartman’s Battle of Ink and Ice also includes some thoughtful reflections upon the attitudes toward and treatment of native guides used by the various Arctic explorers, especially the Inuit of northern North America. Finally, while Hartman’s book includes some helpful maps to guide the reader through various Arctic adventures, the best way to follow this is with a globe handy. In this way, you will see, like no paper map can achieve, the immensity of reaching the North Pole and also the great distance this spot is from any place you have ever visited.

Enjoy.

*https://www.britannica.com/topic/yellow-journalism

**https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1909/09/07/101896076.html?