A conversation with Ryan C. Coleman

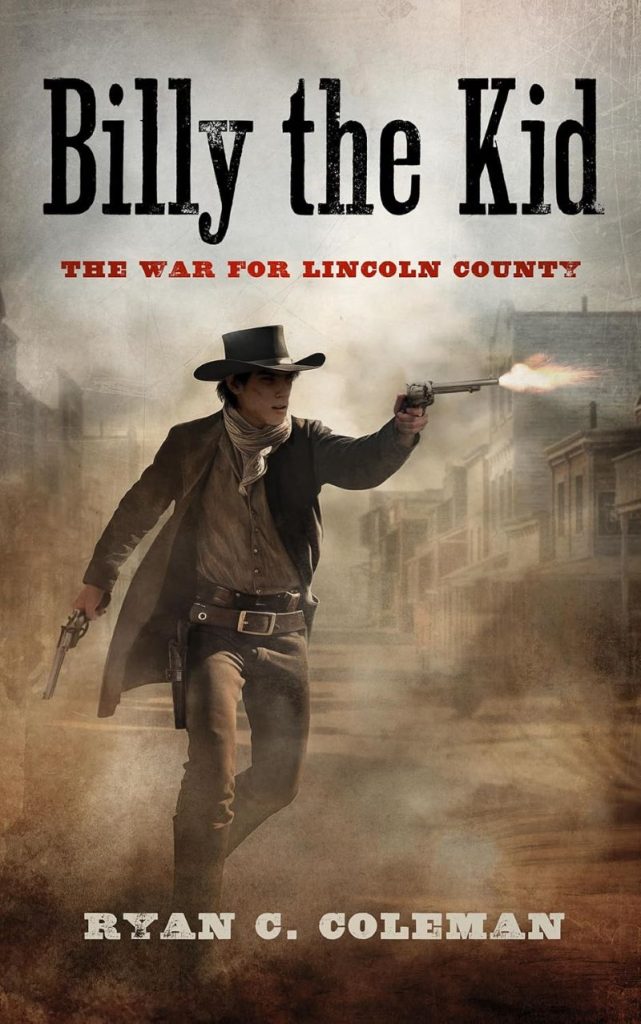

First-time novelist Ryan C. Coleman has penned an authentic account of the short dramatic life of Billy the Kid—born Henry McCarty, aka William H. Bonney—in Billy the Kid: The War for Lincoln County (2024).

Orphaned at age 14 (it is estimated) in the New Mexico Territory of 1874, a young Henry McCarty would morph into one of the most famous outlaws and gunfighters of the era. While these descriptors correctly associate Billy with crime and violence, Coleman’s investigation reveals a much more complicated character whose notoriety derives from an environment rife with violence and corruption.

A glance at the cover of his book reminds one of the paperback Westerns of long ago, often landscaped with a romanticized American West of the late nineteenth century featuring pioneers struggling to tame a savage land. As much as we enjoy these tales with clearly delineated good guys and bad guys—white and black hats, if you will—Coleman takes us well beyond the comforting stereotypes.

While the dime novels of yesteryear were often peppered with an abiding sense of frontier justice achieved with hyper-masculine bravado, Coleman draws from the amazingly rich historical record much in the manner of James Michener; historical fiction that captures the true spirit of actual events.

The result is a bona-fide history of the desert Southwest with fiction inserted only to fill in the gaps and entertain. While this book delightfully reads like some of those old-school paperback shoot-em-ups; it also rests heavily upon the actual events which took place in southern New Mexico and Arizona before these territories became states.

In a remote interview with Coleman, I discovered that much of the work he has done to create his first book is the research work of the historian.

The larger setting for Billy the Kid is the Lincoln County War, which was characterized by a series of revenge killings between rival gangs as they jockeyed for control of cattle interests and the dry goods business from 1878 to 1881. On one side was the Santa Fe Ring who had held sway over Lincoln County—both politically and economically—until John Tunstall and Alexander McSween convinced cattleman John Chisum to back their effort to compete with the Ring.

The conflict was exacerbated with Old World animosities between Irish Catholics —the Santa Fe Ring—and the English-born Tunstall who challenged them. Both sides were made up of businessmen, ranch hands, criminal gangs, and, importantly, lawmen, which gave each side a claim to legal legitimacy. Billy the Kid worked for Tunstall who treated the young man like a son. The opening salvo in the Lincoln County War was the murder of Tunstall, which devastated Billy.

In our conversation, Coleman repeatedly mentioned his desire to stick to these very real events with “authenticity.” He explained that he initially planned to write with a three-pronged approach: the political environment, the important role of Native Americans, and Billy the Kid’s participation, but soon realized that to do justice to all these topics would mean going well-beyond the confines of a single novel.

“I didn’t feel like I could tackle it with the authenticity that it really needed,” he said.

For instance, Native Americans are an important part of this history as they are the target of much of the corruption that motivates the competing gangs. Coleman suggested that including the details of their story, if it were to be done properly and with “authenticity,” might be the subject of another book entirely. To include it here without the degree of research necessary to make it authentic might “end up being more offensive than informative.” To me, this is more the talk of an historian than a fiction writer.

This attention to historical accuracy is why a great deal of actual history is in the form of monographs, paying deep attention to a very specialized topic. And this is exactly what Coleman has done with Billy the Kid.

Coleman’s use of primary and secondary sources of information reveal the unexpected. His sources include contemporary accounts of Billy the Kid’s exploits and also the work of researchers, including Dr. Gale Cooper’s Billy the Kid’s Writings, Words, & Wit (2018). As the writings document, Billy the Kid was not only literate, but eloquent and thoughtful. In several instances, Coleman has Billy picking up a newspaper and pondering the goings on in his day. This not only gives insight into Billy’s intellect but it also becomes an effective device to put the entire novel within the context of the larger world.

The most fascinating revelation for me is that the personal characteristics of Billy the Kid thoroughly defy the persona of “gunfighter.” By almost all accounts Henry McCarty had a gentle soul and any characteristics to the contrary, as Coleman told me, developed as a product of his environment. For instance, after John Tunstall’s death Coleman told me that “a switch is flipped” in Billy who then became deeply motivated by revenge.

Prior to this moment, Coleman describes Billy as “you’re 15, 16, 17, you’ve lost your mother, your step-father has abandoned you, your brother is sent to go work somewhere else… your brother does slide into… a little bit of an opium issue and you’re a kid.”

The movies about Billy the Kid—that Coleman absolutely loves—often portray Billy as a fearless “psychopath,” but the real Billy the Kid was, as Coleman said, “less bloodthirsty, more just ‘I am lost out in the wilderness on my own and I’m looking for a family or something to call home.’”

“All he’s doing,” Coleman adds, “is looking for a home, a family… a community… and he’s finally found it… and then it’s ripped out from under him, in front of him… and he knows who did it, and so, he’s got nothing left.”

After Tunstall’s murder, the violent environment during the Lincoln County War “just takes a hold of him” and “he’s sort of sucked into it… and once he’s in there’s no way out.”

Hewing to the facts does not prevent Coleman from having a little fun with his story. After demonstrating his prowess with a gun, several men ask Billy how he learned to shoot. Coleman’s Billy says, “Gun sorta hits where I point it. Never have to worry much about waywardness.”

When asked about this Coleman said, “As for his sharpshooting abilities, I think he was a pretty good shot, I may have embellished slightly there, but I’m not sure. You know, I’ve always heard he was a good shot, but that also could be… fake history… after his death… well, what makes him cool and what sells dime-store novels?”

In another scene, Coleman offers more personal insight into Billy the Kid’s intellect and his passion. In bed with his lover, Isadora, Billy picks up his copy of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. He explains to her that it is “the story of a precocious boy who’s always getting into trouble, innocent little things here and there, until trouble starts seeking him out.”

It’s also the inspiring, informative, and entertaining story of a couple of nineteenth century American boys with big hearts and gentle souls struggling to manage the hands they were dealt. I think Tom, his buddy Huck Finn, and Billy would have gotten along just fine. And, just as Tom and Huck will forever remain boys in our minds, so will Billy the Kid. He was shot and killed in 1881 at the age 21 or so.

I did not get around to asking Ryan C. Coleman if there is any evidence that Billy the Kid actually identified with the fictional mischief makers Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn. In the end, though, it doesn’t really matter because there is plenty of other evidence to suggest that he very well might have. And, even within the “real” history books, this is often about the best we can hope for.

Catch the New Times Radio Podcast and listen in as Jimmy P. Morgan and Ryan Coleman discuss the making of Billy the Kid https://new-times-radio.simplecast.com/episodes/books-such-a-conversation-with-ryan-c-coleman