“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” ~George Santayana, 1905

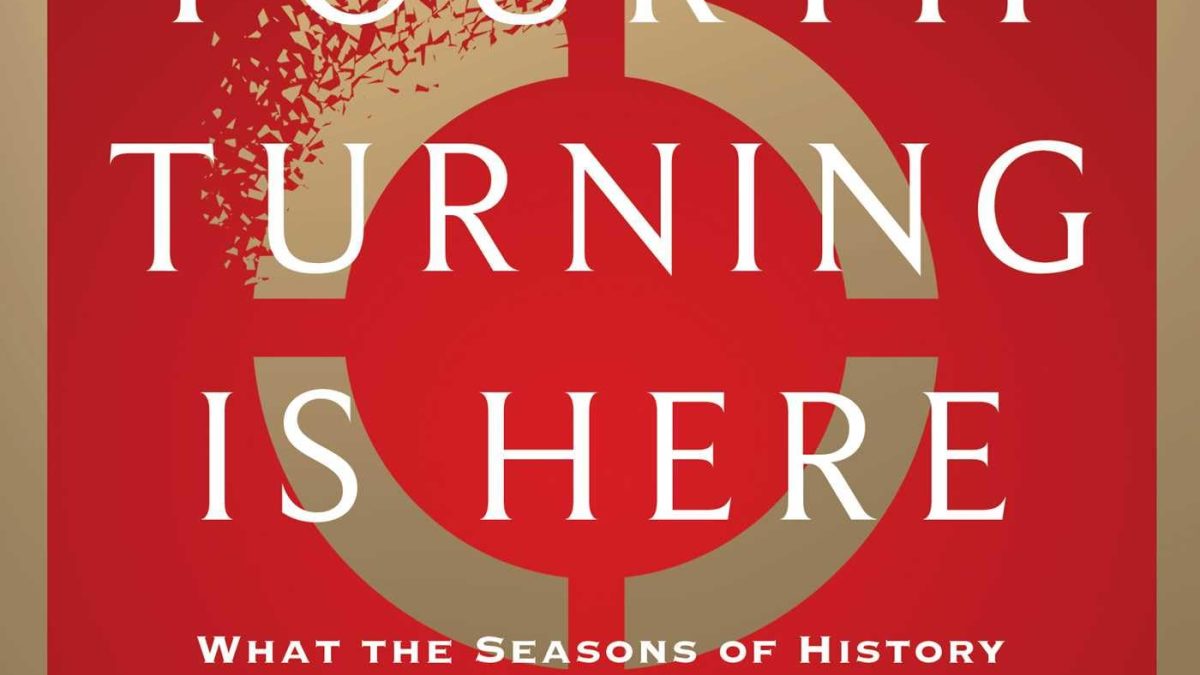

In The Fourth Turning is Here: What the Seasons of History Tell Us about How and When This Crisis Will End (2023), historian, economist, and demographer Neil Howe follows up on over 30 years of work identifying generational patterns of history offering a very plausible framework for what happens next. Howe and his long-time collaborator William Strauss—who died in 2007—first proposed the Strauss-Howe generational theory in the 1990s.

As I recall personally, our world had a very different vibe, or mood, in the ’90s. If this idea of socio-cultural mood change resonates with you—not just the nature of your personal circumstances, but the mood of society going forward —you may be experiencing the very thing Strauss and Howe predicted over a generation ago.

Their generational theory has not escaped criticism for claiming the ability to “predict the future.” A New York Times review of their book The Fourth Turning in 1997 referred to their predictions as “pseudo-science.”*

Whether you buy into their ideas or not, the manner in which they lay out the evidence of the claim is absolutely astounding, particularly considering that we are now living in the future they wrote about.

In general, Strauss and Howe describe modern human generations as seasons that come and go. And, just as winter, spring, summer, and fall give way to another winter, spring, summer, and fall, so too do modern generations follow a similar four-stage cycle.

I offer a quick run-down of four relatively familiar generations to help visualize these ideas.

The vast majority of people alive today have no personal memories of World War II. The youngest who actually served in the war in its final year of 1945 (the last remaining members of the G.I. Generation) are today almost one hundred years-old. And the children who lived through the war years at an age old enough to understand what was happening (the Silent Generation) are approaching or already in their nineties.

The G.I. Generation is also referred to as the Greatest Generation because as young to middle-aged adults during the 1940s, they did most of the heavy lifting both at home and abroad that secured victory.

The Silent Generation is relatively small because their birth years coincide with the Great Depression when birth rates were very low. As Strauss and Howe have written, Silents came of age in the 1950s and are generally known for their conformity and civic-mindedness.

The Baby Boom Generation came of age in the mid to late 1960s and then engaged in the wholesale rejection of their largely conformist parents from the G.I. and Silent generations.

Generation X came of age beginning in the late 1970s when women were beginning to enter the workforce in larger numbers and the rates of divorce skyrocketed. In the wake of Watergate and Vietnam, they developed a cynicism toward government and institutions in general and are largely viewed as being laid back and independent.

While Strauss and Howe have been criticized for the manner in which they delineate and characterize generations, they spend a great deal of time acknowledging these shortcomings.

For instance, while not everyone in a given generation lives and behaves as all others in that group, these generational characteristics offer cultural and sociological trends that inform the passage of time. Also, each generation has its younger and older members who have their own characteristics but do not generally stray far from the generalities of most of its members.

It is also important to note, for our own time in particular, that it is not until the passage of time that we can look back and label generations and their length, so the names that have been thrown about recently for more recent generations will likely be more agreed upon some time in the future.

Finally, just as seasons come and go with a great deal of variability, they ALWAYS come and go in order. However, while the seasons on earth can be measured and dated with great accuracy due to our understanding of the earth’s revolution around the sun, the generational “seasons” of the Strauss-Howe theory are more in flux.

At the heart of generational theory is the “saeculum” (sek’-u-lum) defined as the length of “a long human life” of roughly 80 to 100 years including four generations each roughly 20-25 years. For example, we are living at the end of Millennial Saeculum, including the Silent Generation’s oldest members who were born in the 1920s, the Baby Boomers and Generation X, and finally, the Millennials, whose last members were born in the early 2000s.

Further, as each generation experiences its winter, spring, summer and fall, Strauss and Howe describe each season as a “turning”. Spring is “The First Turning” summer the Second, fall the Third and, as is seen in the title of Howe’s 2023 book, winter is “The Fourth Turning.”

The First Turning is spring and Strauss and Howe call this a “High.” The winter brings all closer together so, during the spring, a sense of community prevails and faith in institutions is restored. It was the Silent Generation coming of age in a post-WWII world that embraced conformity and civic-mindedness.

The Second Turning is summer and called an “Awakening.” Fatigue over conformity sees young people reject the demands of their parents while seeking “self-awareness” and “spirituality.” It was the coming-of-age Baby Boom Generation that rejected the norms of the 1950s and claimed “If it feels good, do it.” and “Hell no! We won’t go!”

The Third Turning is fall and called an “Unraveling.” Institutions begin to fail and the positive community spirit of the High has given way to a strong sense of individualism. It was Generation X coming of age in the 1980s after Watergate and Vietnam that was disillusioned with government. Think Ronald Reagan’s view of the role of government.

The Fourth Turning is winter and called a “Crisis.” Unfortunately, a Fourth Turning is an era of chaos and destruction culminating in a “Crisis Climax;” either an external “Great Power War,” an internal civil war, a massive economic crisis or, more likely, some combination of the three. It may or may not conclude favorably and may or may not be severe. One thing it will be, according to Straus and Howe, is transformative.

It is the Millennial Generation now coming of age and in their peak working years that will largely determine how we respond to this predicted Crisis Climax, much as the G.I. Generation responded to World War II.

Strauss and Howe also assign each generation an “archetype” depending upon the season in which each generation comes of age. Heroes deal with the Crisis and set the stage for rebuilding during the High. Artists conform to the freshly established and trusted society with a strong sense of community. Prophets, who were pampered children during the High, begin to look spiritually inward while beginning to reject the burdens of conformity. Nomads grow up as unprotected and freewheeling children who come to reject social institutions during an Unraveling. This leads to the next Crisis.

Of course, the previous Fourth Turning (Crisis) ended with World War II marking the end of the Great Power Saeculum. Eighty years later, The Millennial Saeculum is now coming to its end.

Since the dawn of modernity, the saecular pattern has held for 24 Anglo-American generations beginning with the War of the Roses Crisis Climax in 1485. Howe describes this as “an unparalleled quarter century of internecine butchery – in which dozens of the highest nobility were slaughtered, kings and princes murdered, and vast landed estates expropriated.” Fifty years later or so, the Protestant Reformation characterized an Awakening, the spiritual counterpart to Crisis in the saeculum.

About fifty years after that, the English defeated the Spanish Armada which had posed an existential threat to England (Armada Crisis). Howe writes of this “miraculous victory” that transformed England from a “strife-ridden ‘heretical’ nation [which] emerged [as] a rapidly growing commercial power at the heart of a nascent global empire.”

According to Strauss and Howe, this pattern of a Crisis Climax leading to a sort of “golden age” during the High, a spiritual revelation of sorts during an Awakening, a subsequent turning inward and rejection of institutions during the Unraveling, and eventually another Crisis, has been repeated time and again.

England’s Glorious Revolution of 1688 occurred exactly 100 years after the Armada Crisis of 1588. In its wake, during the High that followed, a transformed England adopted the English Bill of Rights, secured the independence of Parliament and limited the power of the monarchy.

This Glorious Revolution Crisis was experienced in England’s American colonies, as well. As Howe writes, “English-speaking America entered the Crisis a rude and fanatical backwater; it emerged [in a High] a stable provincial society of learning and affluence.” One historian cited by Howe offers that “it would be no great exaggeration to call the years 1670 to 1700 the first American revolutionary period.”

The Crisis Climax for this New World Saeculum was 1691. The next occurred just under 100 years later at the end of the American Revolution Crisis. Eighty years later was the American Civil War and eighty years after that was World War II. We are now 80 years removed from the end of the last Crisis Climax in 1944.

With mountains of evidence and numerous charts, Strauss and Howe have clearly identified the discernible patterns of modern history over seven saeculae spanning over 500 years. Again, Howe acknowledges the very human-inspired limitations of their theory. Howe identifies the moments of history that do not line up neatly with their generational theory. He explores “random accidents” and “episodic technological discoveries” that might shorten or lengthen a generation. He examines closely a saecular anomaly which occurred following the Civil War Crisis in which “no generation came forward to fill the usual Hero role of building public institutions…” following the Crisis Climax. He offers that “the [Civil War] Crisis congealed so early and so violently, most of this generation [the presumed Hero Generation] was still in childhood at the end of the war – and emerged more shell-shocked than empowered.”

As further evidence, Howe describes other cultures that shared the organizational characteristics of the modern (Western) world and suggests that the same social forces were at work. He also writes that as the United States has begun to influence and shape much of the world in the twentieth century; it appears that much of the world beyond the West has been merging into something of a global generational cycle.

As for us, today, Howe offers the Great Recession of 2008 as the beginning of the most recent Fourth Turning and the opening of the Millennial Crisis era. Add to that the election of Donald Trump in 2016, the pandemic beginning in 2020, and the growing sense of hostility towards one another. These Troubling developments will merge into a Crisis Climax.

By examining the time between the onset of a Crisis to the Crisis Climax during the seven saeculae, Howe sees an average of about 25 years. Adopting the average for the sake of narration, with a Crisis era beginning in 2008, Howe predicts that the Millennial Crisis will reach its Crisis Climax in 2033.

Nearing the end of this fascinating book, Howe begins to write with fewer qualifiers and more certainty; as if the writing of the book has all-but-confirmed in his mind the Strauss-Howe generational theory. As Howe writes, the “rhythm [of the saeculum] has been at work since the dawn of modernity.” He concludes that, “sometime before the mid-2030s, America will pass through a great gate in history, commensurate with the American Revolution, The Civil War and the twin emergencies of the Great Depression and World War II.”

As to George Santayana’s advice to remember history so as not to repeat it, it seems that, remember or not, we shall repeat it.

Buckle up, friends!

*https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/97/01/26/reviews/970126.26lindlt.html